by Jeannette de Beauvoir

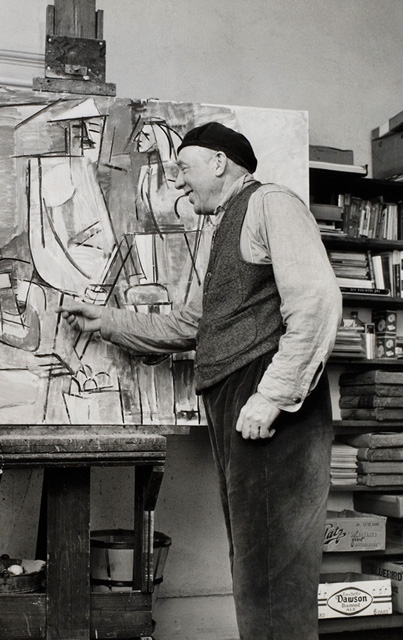

After nearly a century, some of Karl Knaths’ early work has finally found its way home, and the Bakker Gallery is sharing it with Provincetown. “A good client of ours—who studied with Knaths—discovered an unpacked crate of his drawings in her barn that had remained unopened since the pieces had been loaned to the Everson Museum of Art for their important 1982 exhibition,” says gallery owner Jim Bakker. “Like so many of our artists whose work remained unseen, perhaps forgotten, and thus unappreciated for decades, this is an opportunity to bring Karl Knaths’ early works on paper back to Provincetown.”

Knaths was originally apprenticed to a baker in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, but while still in high school he became caretaker and set designer for the Wisconsin Players theater group, enabling him to leave baking behind; he eventually studied at the Art Institute of Chicago. He got a job as a security guard at the famous 1913 Armory Show and was, in his own words, “awed and confused” by the modernist work he saw there. Cézanne’s blocks of color in particular interested him and later influenced his own work: “both artists,” writes Virginia Mecklenburg, “blended an intuitional understanding of structure with motifs drawn from observed nature.”

“I tend to see an artist within the context of Provincetown as an art colony instead of strictly as an individual,” he (Bakker) says. “I’m much less interested in what kind of an artist Knaths was than I am in who he was and how he was connected to the community.”

From 1912 to 1917 Knaths was at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, but then rejoined the Wisconsin Players to do set design for the group’s east coast tour. When they arrived in Provincetown, Knaths felt he’d come home. “Karl came to Provincetown for a variety of reasons, the main one being to study with Charles Hawthorne,” Bakker gallery managing director Spencer Keasey says. “He also came because Ross Moffett, his friend at the Art Institute of Chicago, had arrived years before to study with Hawthorne. Perhaps it was one of those synchronistic events that the Wisconsin Players (for whom Knaths did set design) were in Provincetown at the same time.” Theater was alive and well in town, and the studio Knaths rented had previously been occupied by Eugene O’Neill.

From that moment on, his art drew repeatedly from his Provincetown surroundings: deer in landscape settings, clam diggers returning from work, fishing shacks, boats in the harbor, horse barns, duck decoys, and fishing paraphernalia. These themes were important to Knaths, who believed that “whatever is to be realized by the painting should arise through the use of pictorial elements in a thematic way. The surface being the prime element, it is possible to manipulate full spaciousness within its flat terms.”

Knaths worked out intricate charts for color and musical ratios, which he used to determine directional lines and proportions in his paintings. “Knaths was more of a pathfinder rather than an innovator,” says Bakker. “To me, finding and following a path within laws that guide us ensures we adhere to certain boundaries. It’s those boundaries that are mathematical; to me they are the thick ink angled outlines of his subjects in these works. But sometime their placement seems nonsensical. Or not. Because these works are quick impressions, often to be worked into larger planned canvases, it takes a moment to figure out what’s what. But once you see it, it’s clear. He’s adhered to a principle, a framework, an outline—both figurative and literal.”

Yet his system was not entirely about the rules; there’s a lyricism in his approach to Cubism in particular that art historian Tom Lawin characterizes as romantic rather than either literal or academic. “At some point, Knaths discovered Wilhelm Ostwald’s color system,” writes Mecklenburg. “Based on color and not on light, the Ostwald system was devised as a way of ordering color, and was quite popular among American artists of the time. Knaths not only used this system, he harnessed it to a complex set of mathematical and geometrical relations—akin to musical proportions—so that the theoretical foundations of his art were both complex and highly worked out.”

He connected art with music and listened to his conservatory-trained wife’s piano recitals for inspiration. “Music greatly influenced Knaths’ life, as it has mine,” says Bakker; Knaths himself said that “there are definite, measurable correspondences between sound in music and color and space in painting: specifically, between musical intervals and color intervals and spatial proportions.”

Both Bakker and Keasey see the artist as deeply rooted in Provincetown. “I love the spontaneity of his works and how Knaths captures the essence of Provincetown life, often in just a few brush strokes,” says Bakker, and Kesasey agrees. “I tend to see an artist within the context of Provincetown as an art colony instead of strictly as an individual,” he says. “I’m much less interested in what kind of an artist Knaths was than I am in who he was and how he was connected to the community. It’s important to me to understand he married Agnes Weinrich’s sister, Helen. It’s even more important to know that, according to Josephine Del Deo, ‘he was a man of matchless diligence in the pursuit of his art and his way of life….he rose early and walked often in the direction of the moors along the road to Herring Cove where his ‘umbrella’ of a blue heron awaited him…’ My partner and I walk that same walk throughout the year, and in that lovely image, I feel more connected to Knaths and my sense of place within Provincetown.”

Bakker is thrilled about the exhibit. “Like his friend [Ross] Moffett, who coincidentally died just four days after Karl, Knaths’ oils and larger paintings are prohibitively out of reach for most collectors of Provincetown art,” he says. “These smaller works on paper present an opportunity for those same collectors to add Knaths to their collections. Whether it’s Edith Lake Wilkinson, Evelin Bodfish Bourne, Florence Brillinger, or someone as widely recognized as an important American painter as Karl Knaths, this is another treasure trove we’re excited to share with the community.”

Karl Knaths’ work is on exhibition at Bakker Gallery, 359 Commercial St., Provincetown, July 21 – August 13. There will be an opening reception on Friday, July 21, 6 – 8 p.m. For more information call 508.413.9758 or visit bakkerproject.com.