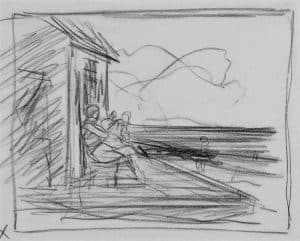

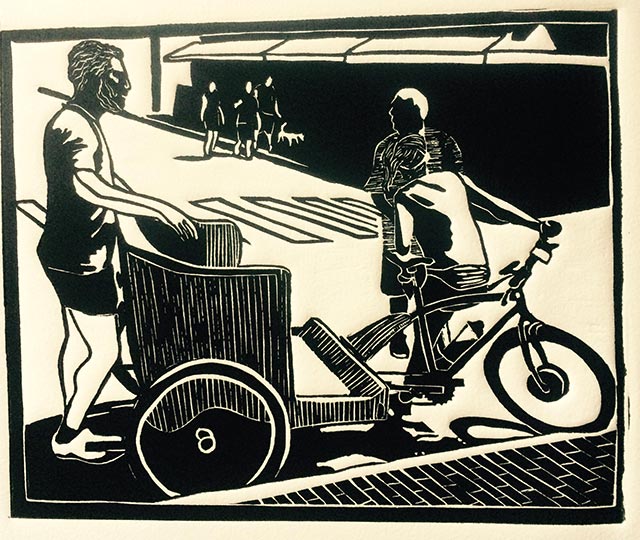

Spew (ink drawing on Merillo heavyweight paper, 2013, 14 x 24”)

by Steve Desroches

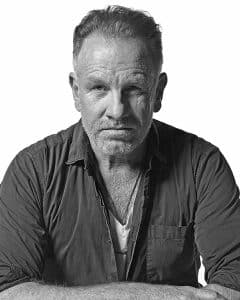

William H. Skerritt sees a story in most everything he sees as an artist and a scientist. A geologist by training and an artist by passion, Skerritt views the natural world as full of secrets hidden in plain sight, while the creations of humans stand in an attempt to make some order out of all of that beautiful chaos. We’re surrounded by stories if we just know how to read them. Pick up a rock; all of those lines, spots, and speckles are a record of millennia of a variety of natural processes. And the moment you hold that rock is but a mere pin point in a vast expanse of time.

“I see the duality of manmade things and that nature is constantly reclaiming its own,” says Skerritt. “You make a building and leave it alone and nature eventually reclaims that building.”

What goes into creating any geologic formation feels very much like the hands and mind of an artist to Skerritt. Each artist’s viewpoint is sharp and distinct, even if working in the same medium as thousands before them. Be it an etching or a white line print (two of Skerritt’s chosen methods), no two prints are identical, even when done by the same hands. In both cases, there are external forces at work with innumerable variations affecting the outcome. It’s part of the thrill to contemplate what went into the formation of either a cliff side or a drypoint print.

“I found that geology is as much of an art as a science,” says Skerritt. “In that a lot of it is visualization of the process you can’t see happening, but that you know happened.”

In his show Lines: Simple and Complex Parts 2 at the Hutson Gallery Skerritt focuses on his white line woodblock prints, linocuts, and ink drawings. And as with geology, the lines that divide tell as much of the story as what lies on either side. In particular, his drawing Spew features a massive arch that is a cross section of the Earth, with both natural and manmade elements, both of which emit contaminants into the atmosphere. One we can control, the other, like volcanoes, we cannot.

The graduate of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and retired geologist with the New York State Department of Transportation has found that through his work, art was often times the best way to communicate the science behind the concepts he was trying to explain to politicians, engineers, and others making decisions that affected the roads and highways of the Empire State. When working on a study of how to reduce skid risks, Skerritt found that his drawings of the variety of problems and solutions ultimately proved effective in describing a complex issue.

“I see the duality of manmade things and that nature is constantly reclaiming its own,” says Skerritt. “You make a building and leave it alone and nature eventually reclaims that building. Look at the Netherlands. They have to constantly maintain the dykes to reclaim the land. Nature is relentless.”

Just as the natural world never stops, Skerritt is always seeing a muse for his next work. As his life as an artist began through work in geology, he initially started creating scrimshaw, which he sold on Nantucket. But he abandoned the art form in response to increased environmental awareness about endangered species and the negative impacts of the ivory trade. It was then that he moved toward putting the drawings he once did in scrimshaw to paper and in various printing methods. And in particular, it was his childhood Cape Cod vacations that drew him to learn the white line print method he saw over the years on visits to Provincetown, where the method was created about 100 years ago.

The story, the process, the creation: it’s always on the mind and fingertips of Skerritt. His white line print The Cloche No. 2 in the show is a portrait of his wife shortly after she bought a hat during a stroll around SoHo in Manhattan. It captured a moment, and a subject, in a way that to Skerritt features his wife as he “knows her to be,” but for the casual viewer, it encapsulates a narrative with its colors and lines the same way it may be if strolling the beach picking up stones. You weren’t there for the moment of creation, but the end result is proof of the dynamics and energy that happened prior. Those moments are all around us.

“I find inspiration everywhere,” says Skerritt. “I sat down to eat not long ago and I looked at the asparagus and said, ‘I know what drypoint of the asparagus stock I can do.’ So I made a piece of the asparagus stock. I’m in the moment, and I am enthusiastic, and I don’t know where it’s going to go.”

Lines: Simple and Complex Parts 2 is on exhibition at the Hutson Gallery, 432 Commercial St., Provincetown, July 21 – 27. Part one of the show is still on view there through July 20. For more information call 508.487.0915 or visit hutsongallery.com.