Intersectional Identity in Call Her Ganda

by Rebecca M. Alvin

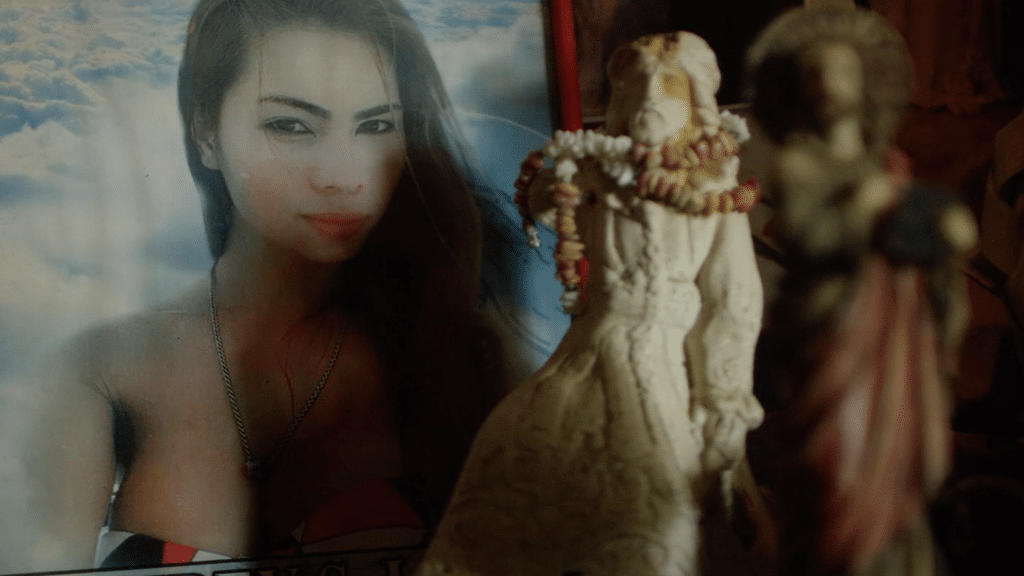

Above: A photograph of slain Filipina Jennifer Laude. Photo: Mike Simpson

Nearly four years ago, U.S. Marine Joseph Scott Pemberton committed a crime in the Philippines. After meeting in a bar in Olongapo City, Pemberton and Filipina Jennifer Laude went to a hotel room to have sex. Shortly thereafter, Jennifer was dead. She was found by her friend and the hotel receptionist, half-naked, strangled and drowned in the toilet. Pemberton, a native of New Bedford, Massachusetts, was tried and eventually convicted of killing Jennifer—the first U.S. serviceman to ever be convicted of a crime in the Philippines, despite numerous other cases during the 100-plus years of U.S. presence there. The murder of Jennifer Laude was not only a case of violent transphobia, it also re-ignited long-held tensions among the indigenous Filipinos around their relationship with the United States. It is this tangled web of racism, transphobia, imperialism, and national identity that became the subject of director PJ Raval’s new documentary, Call Her Ganda, which just had its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York last month.

“It’s been interesting because my previous films have all dealt with LGBT content of some sort, and this is the first one that I’ve done in the Philippines… I’ve always been described as a ‘queer’ filmmaker and no one ever really mentions that I’m Filipino or Asian-American,” says Raval in a lounge at the Roxy Hotel. “For me, it was all my worlds combining. And not only being Filipino, but being Filipino-American, which I think is a very specific point of view.”

Raval is here with Virgie Suarez, the attorney for the Laude family, and Filipina trans activist Naomi Fantanos, who was also a friend of Jennifer’s. Both women appear in Call Her Ganda

as key interviews and each has her own contribution to this intersectional story: Suarez as expert on the legal case and Fantanos as a voice for the cultural and political context for transphobia and LGBT+ activism in the Philippines. But Call Her Ganda provides additional perspectives on the Laude case by following Jennifer’s heartbroken mother, who is determined to get justice for her daughter, and Meredith Talusan, a Filipina-American trans journalist covering the story for Buzzfeed.

Raval says, “It was really great when I discovered Meredith because I thought, ‘Here’s someone who is going to take this investigative approach, which is pretty much what I am going to be doing with the documentary, but rather than making it about me I can make it about her. She can ask all the questions that I might want to ask.’” Raval laughs at the idea of hiding behind Talusan, but also says her participation was instrumental because the film becomes as much about her journey covering the story as it is about the Laude case itself. “It was important for me to tell the story of people from the Philippines and from the point of view of a trans journalist. I think another film could have existed where it was all from the point of view of the American marine, the family in the United States, but I was also very conscious of wanting it to be about following these character, these subjects and their own experiences.”

Pemberton was initially not apprehended by Filipino authorities because of a clause in the Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) between the United States and the Philippines. Much of the controversy around this case came from the desire of Filipino people to be able to protect their own citizens and obtain justice through their own legal system when American soldiers commit crimes in the Philippines. Prior to the Laude case, there had been another case in which a woman was gang-raped and beaten by U.S. soldiers and left to die in the streets. No one was convicted and the charges were dropped when the victim was given a U.S. visa. Pemberton has been found guilty, and according to Suarez, the case is now pending before the highest court in the Philippines. He is being held in the Philippines, but in a U.S. guarded facility, separated from the larger prison population, and with access to computers and online education—things Suarez says no Filipino prisoner would ever be given access to in prison.

As the film shows, this conviction is a major victory and it came about after intense protests broke out in the Philippines, something that was not well reported here in the U.S. Perhaps more significantly, the protestors were not simply LGBT+ activists, but rather a wide range of Filipinos who saw Jennifer’s death as a horrific crime that demanded justice. Even with lingering questions regarding whether or not Jennifer was a sex worker—something that along with her status as a trans woman would have made a huge difference here in the United States—the broader community was rightly outraged.

“There are women, there are farmers, there are fishers, there are families coming from the urban poor, and even the youth joined the protest, and the teachers, and members of the academe, and of course the LGBTQ community,” Suarez explains. “The case is reflective of the unequal relationship between the U.S and the Philippines… and so these are matters that are actually owned and embraced by different sectors.”

Raval, who had not previously spent too much time in the Philippines, despite his heritage, says he was surprised to see how active and visible the LGBT+ community is there. At one point in the film, we learn about a rich history of transgender shamans in the indigenous culture who were wiped out by Spanish missionaries who demonized their trans identities as a way of gaining Christian converts.

Fantanos is proud of the accomplishments of her community, despite obstacles. “It’s quite interesting because we’re living in a very dangerous time, with the Duterte Administration [which is very homophobic]. Luckily, the [LGBT+] movement has been very vibrant and alive for the last 30 years, so we were able to get an anti-discrimination draft law approved in Congress,” she says. “It’s a product of 20 years of legislative advocacy work, so we’re actually quite ahead of the U.S. in that sense.”

Raval’s skill as a documentary filmmaker is apparent in his ability to weave all of these issues together into a film that never shields its audience from the complexities of this case. In fact, in one particularly poignant part of the film, Talusan even travels to New Bedford to try to understand where Pemberton came from. Although the film does not include interviews with Pemberton or his family, Talusan does interact with people in New Bedford, coming face to face with the kind of run-of-the-mill transphobia that still exists even in liberal Massachusetts, as well as a stark difference in reactions to the case. Where in the Philippines and in Asia the case was an enormously important one, here it is met with an indifferent shrug.

“I think for me that trip was so important because I think what Meredith is exploring there, and what I was exploring there also, is that Pemberton is a person. Yes, he’s symbolic of all these things, but at the end of the day, he too has a mother,” Raval says. “It’s part of this larger structure and part of this larger history that is problematic. So in a lot of ways, his choice to go into the military, the fact that he’s brought overseas. How much is he educated about the Philippines? What is his point of view going in, what is he encouraged to do, what is he encouraged to believe and think? For me it was important to include a lot of the historical footage and see what his cultural training might be… We have to think about all of the social conditioning that’s happening and all the messages that someone receives, regardless of where they’re coming from.

For more information on where you can see Call Her Ganda visit the website at: callherganda.com.