by Steve Desroches

“Where’s my Roy Cohn?”

That’s what President Donald Trump asked in a moment of rage, according to the New York Times in January, when he learned that the White House lawyers were unable to dissuade Attorney General Jeff Sessions from recusing himself in the investigation as to whether or not members of the Trump campaign worked with the Russians to influence the 2016 election. Cohn is the lawyer who played a major role in the kangaroo court trial of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg that sent them to the electric chair for espionage, Republican Senator Joseph McCarthy’s right hand man during the Communist witch hunts and the subsequent “Lavender Scare” of the 1950s, the ham-fisted lawyer for the scandal-plagued Studio 54, and Trump’s attorney for 12 years, becoming Trump’s mentor. If Trump had asked that question in the summer over those years, the answer would most likely have been: “Roy Cohn is in Provincetown.”

Cohn first began coming to Provincetown right about the time he became Trump’s attorney in 1973, defending him and his father, Fred Trump, who were under fire from the Justice Department for violating the Fair Housing Act by discriminating against African-Americans in multiple residential properties they owned throughout New York City. They settled the case with no admission of guilt after countersuing the federal government and losing. So began an oozing partnership between Cohn and Trump, where the former taught the unscrupulous real estate mogul to approach every situation like a panicked gorilla: lying, litigious, and never, ever admitting you were wrong. Cohn also pledged and demanded loyalty to the point of Machiavellian codependency, and played a devilish matchmaker, introducing Trump to figures like Roger Stone and Rupert Murdoch.

Summers in Provincetown at that time were a wild convention of outsiders, rebels, artists, radicals, and the working class that gave the town its heartbeat, as well as shuffling tourist crowds that filled the streets, and often times scoundrels, as it was the last gasp of lawlessness on the Cape tip that allowed its libertine culture to grow to full bloom by the 1970s. Provincetown was also a place of secrets. And in those days, without the Provincetown Community Space on Facebook and the like, messages were spread the old-fashioned way, through street gossip, drunken aspersions, or whispered warnings. But for a variety of reasons, be it for personal freedom, a revulsion of mainstream society’s values, protection from discrimination, or for criminal pursuits, what happened in Provincetown stayed in Provincetown, long before Las Vegas turned that idea into a tourism campaign. That gave Cohn cover in Provincetown as a deeply closeted gay man who reveled in slithering around the town’s frenzied Bacchanalia, knee-deep in booze, hustlers, and hypocrisy, something made quite evident in the 1988 book Citizen Cohn, written by Nicholas von Hoffman, who also wrote the Life magazine story “The Snarling Death of Roy M. Cohn” that same year.

Even in Provincetown, Cohn would often have a beautiful woman at his side as a beard, one that was about as convincing as peach fuzz on an adolescent boy’s chin. Speaking of which, locals nicknamed the ever-revolving chain of very young men (so young it raised many an eyebrow) that always followed Cohn his “Boy Scout troop.” That being said, many in current day Provincetown don’t know Cohn spent as much time as he did here, as he often preferred the comfort of private parties rather than hitting the town, where he might be recognized or outed. His imprint on the town now is little more than a whiff of sulfur.

In those years in Provincetown, Cohn often did go unrecognized in a town full of all kinds of characters. But there were certainly those who remembered him from the McCarthy hearings or later for his high-profile work for Studio 54, which had him doing battle with the Carter administration and later trying to weasel his way into the Reagan administration via the closeted gay men like himself who were willing to turn against their own to satiate their own ambitions. In the early 1970s Deb and Dennis Minsky were a young couple on the cusp of marriage when they worked at Ciro and Sal’s, she a hostess, he a busboy. They both knew exactly who he was and what he had done. He paraded in on occasion, often without a reservation at the height of summer, demanding a table for him and his large party of young men, acting arrogant and pugnacious.

“Just looking at him was a challenge,” says Deb. “I don’t like Roy Cohn and I don’t like what he represented. He once offered me a $20 tip, which in those days was huge. I couldn’t accept it from him. I just said, ‘No thanks’ and walked away.”

There was still a substantial population of left-wing intellectuals and activists on the Outer Cape, including the Meeropols, whose patriarch Abel wrote the song “Strange Fruit” made famous by Billie Holiday and who, with his wife Anne, adopted the orphaned Rosenberg children, Michael and Robert. This substantial part of the Outer Cape population also knew exactly who Cohn was. Dennis recalls one fine summer day when Cohn was sailing in the harbor and overturned his boat. There was a small group of old leftists having cocktails on a deck overlooking Provincetown Harbor in the East End. Custom and culture dictated providing assistance to those in distress on the water.

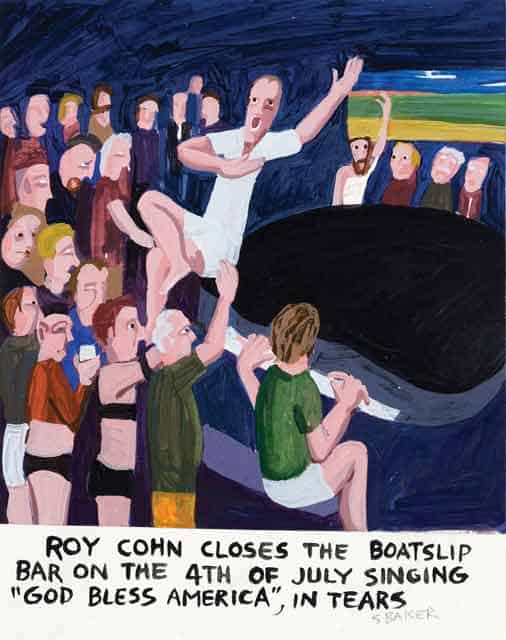

In large part Cohn could do whatever he wanted. He was powerful, well connected, and feared. A lifelong registered Democrat, Cohn was the darling of the Republican Party for his ability to get it done, by any means necessary. And he was the go-to legal defense for a variety of mafia top dogs like Tony Salerno, Carmine Galante, and John Gotti. While he might have behaved in a brusque and entitled manner, he kept a rather low public profile in Provincetown, even though in the last years of his life he rented a cottage from Norman Mailer in the East End and would throw parties that attracted celebrities and power brokers to the Cape tip. But the one antic that Cohn did in the most public fashion became the stuff of Provincetown legend. Cohn loved a piano bar and Provincetown, like now, was full of them. At last call he would rise to his feet or hop on the piano and sing “God Bless America” at the top of his lungs.

“He was creepy, creepy, creepy,” says legendary piano man Bobby Wetherbee. “He would sit in this corner in a deuce at the old Crown and Anchor with a boy that looked like a child. He seemed so little. Hunched over. Just a little guy. He never made himself known until it was time to sing ‘God Bless America.’”

The Crown and Anchor then was a very different place than now, though Wetherbee still entertains there. Back in those days it was owned by Staniford “Stan” Sorrentino and was frequented by people like Cohn and James “Whitey” Bulger. According to Wetherbee, Sorrentino lit up whenever Cohn showed up, though many in the bar felt repulsion. By the time Sorrentino was convicted of tax evasion Cohn was dead. Had he not been, perhaps he would have helped his friend who spent six years on the run before turning himself in to federal marshals in Mexico.

These recollections of Cohn often get lost in the ether of Provincetown’s storied history. But prior to Trump’s election, the person most responsible for a renewed consciousness of Cohn is the playwright Tony Kushner who made Cohn a character in the masterpiece Angels in America, the two-part epic play in which Cohn is haunted by the ghost of Ethel Rosenberg. Kushner and his husband spend a lot of time in Provincetown, owning a home here and walking the same streets Cohn once did. Kushner says that Trump being a “blowhard, psychotic narcissist” and Ronald Reagan being “sociopathic in some way” makes it easy to see Cohn’s influence and why such people would have a relationship with such a man as Roy Cohn. And with Trump in office, it’s like a shriek from Cohn’s grave.

“We’re in terrible danger,” says Kushner about the state of our democracy and republic. “There’s no hyperbole in saying that.”

Cohn was disbarred for unethical behavior and then died of AIDS in 1986, something he denied having until his dying day, even though he used his connections to get on early HIV drug trials while publically maintaining he had liver cancer. He left this world holding true to his belief of making the lie big and then continuing to tell it. Nevertheless, he died a broken, pathetic man, bitter that even with all his power he ended up in such sad condition. He was 59 years old.

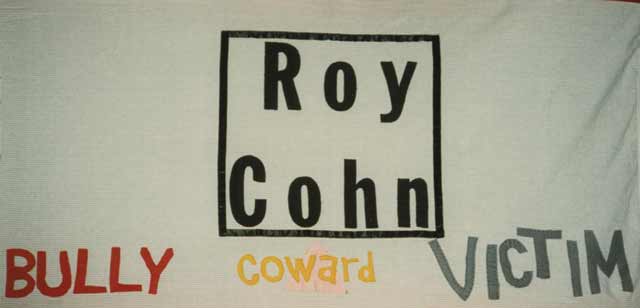

About two years after his death a panel that simply said: “Roy Cohn: Bully, Coward, Victim” was anonymously sent for addition to the AIDS Memorial Quilt. “I was so moved when I saw Roy Cohn’s panel on the Quilt,” says Kushner. “It took me seven and half hours to make the same point.”