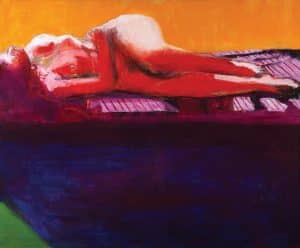

Helen Frankenthaler and the Provincetown Muse

by Rebecca M. Alvin

All images from the Collection Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, New York, except where noted.

TOP IMAGE: Frankenthaler in her studio “in the woods,” Provincetown, Massachusetts, 1968.

Fluid, colorful, organic. Simultaneously reflecting the feeling of nature without actually representing its physicality. Shapes and colors that appear to almost overcome the lines necessary to paint them. The work of Helen Frankenthaler stands in bold contrast to other abstract expressionists who preceded and indeed influenced her, Jackson Pollock, perhaps most starkly. While both Pollock, as the originator of “action painting” and Frankenthaler made works that evoked a kinetic spontaneity, their revelations about motion and the control of paint on the abstract canvas are entirely different. While Frankenthaler was inspired by seeing Pollock’s methods, working with his large canvases on the floor rather than on the wall, working with different kinds of brushes and paints than one traditionally associated with fine art, and the freedom of his gestures, her work pushed abstract expressionism into a new realm, one entirely her own. And summers in Provincetown, as it has been for so many other great artists, were vital to her development and growth, particularly clear from the works shown in the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM)’s grand summer exhibition of her works, Abstract Climates: Helen Frankenthaler in Provincetown, on view through September 2.

But while Frankenthaler could, and did, paint everywhere, the emotional content of what she painted was quite specific to the places and moments that stayed with her, what she referred to as “climates.”

“They’re really memories,” Motherwell concurs. “They’re really experience-memories of how it felt when she was there, rather than the actual view. And that’s why she’s not a landscape painter; she’s really someone whose work is inspired by landscapes.”

Although an abstract painter, it cannot be denied that Frankenthaler’s work is imbued with the elements of the natural world, most notably a connection to water, which can be seen in the way her paints are applied, the innovative soak-stain method she invented, and her manner of controlling and letting go of control of the flow of paint on the canvas. By diluting her paints (first done in the 1950s with oil paint and then later in the 1960s with acrylics) and pouring them on the canvas in such a way as to form puddles of paint to be manipulated by the artist directly on unprimed canvas, Frankenthaler’s work features washes of color soaked right into the canvas, rather than sitting on top of it, as we saw with her predecessors. In doing so, the work takes on a uniquely organic quality that speaks of a very deep, visceral connection to the natural qualities of water, regardless of the specific inspiration for the work.

In fact, it is difficult to look at the works and not find oneself—no matter how steeled against it one is—seeking out physical elements from the environment, especially when so many of the paintings have names that seem to ask us to do this, like Breakwater, Blessing of the Fleet, and her most famous painting of all Mountains and Sea. Abstract expressionism is not about representing the literal, physical reality of a subject, and yet the existence of such titles points to an interesting dynamic in the artist’s process.

“People like Pollock numbered their paintings, which really forced people to look at the painting and not at the title, and Helen just couldn’t remember the numbers attached to the paintings well enough for her to be able to reference her paintings that way,” Motherwell explains. But, she adds, “her titles got more and more abstracted, too, as she got older, I think as a way of trying to get people to not try to place the image onto the title. So I know that she felt conflicted about it.”

Frankenthaler came to Provincetown first in 1950 to study with Hans Hofmann. But it was several years later, after marrying artist Robert Motherwell, that Provincetown became a place of real importance to her. The show features work done in Provincetown between 1950 and 1969, offering a perfect encapsulation of the influence of the town and the times on Frankenthaler’s work.

“During that time her work changed dramatically from very structured, cubist drawings and more realistic paintings to complete abstraction and almost minimalism in the very last paintings from 1969. I think that one of the things that the show really demonstrates is her willingness to take risks and her willingness to experiment throughout her career,” says Motherwell. On a technical note, she adds, it was also a time that is important to her overall body of work because it was when she switched from the thinned oil paint she used early in her career to water-based acrylics.

But the exhibition also includes notes, letters, an engagement diary, and snapshots that offer a view of a particular moment in the artists’ colony and give a sense of what appealed to her, as well as numerous other artists, about Provincetown as a unique space for creative engagement. While Frankenthaler was extremely devoted to her work, even choosing not to have a telephone while in Provincetown so as to ensure dedicated time for painting without distraction, she also participated fully in the social and cultural life of the town and its artists, eccentrics, and intellectuals.

“Both physical environment and landscape and the cultural rituals that happened here fed her work in a way that no other place has,” says Motherwell. “The tides go in and out and the colors change depending on the light, and all that was, I think, really important in terms of giving her ways of thinking about the landscape and her memory of it that she was able to convey here.”

Abstract Climates: Helen Frankenthaler in Provincetown is on view at Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 460 Commercial St., through September 2. Lise Motherwell will give a talk “Frankenthaler in Context” on Tuesday, July 31, 6 p.m. Tickets ($10) can be purchased at the door. Numerous additional public programs related to the exhibition will be happening throughout the exhibition run. For more information call 508.487.1750 or visit paam.org.