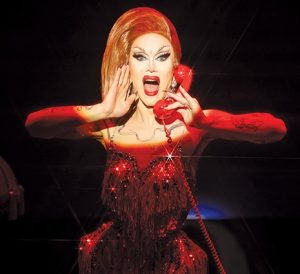

Singer Ari Up onstage with The Slits

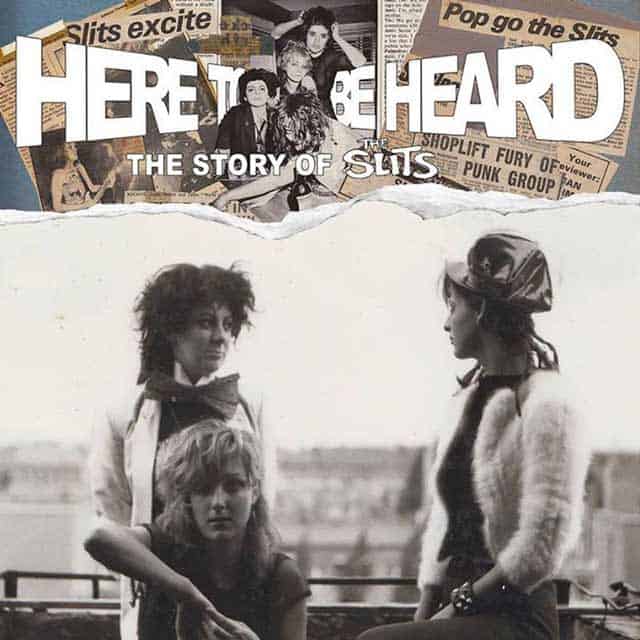

Punk, Power, and Palmolive in Here to Be Heard

by Rebecca M. Alvin

At first glance, Paloma McLardy appears to be just like any other 63-year-old woman you might meet on Cape Cod. Her accent may give away her status as an immigrant born in Spain, but there is nothing in a cursory interaction with her that would reveal her past. A revolutionary in sheep’s clothing, McLardy spent her youth in the squats of London in the late 1970s living with her boyfriend Joe Strummer (before he changed his name from John Mellor) of The Clash, fending off the advances of a teenaged Sid Vicious, and most importantly, fiercely banging on the drums as Palmolive, drummer for punk’s first all-female band, The Slits.

Of course no one can be reduced to what they appear to be at first glance, but while the decades between then and now have seen McLardy transform herself both inside and out, there is a certain thread that runs through it all, from her childhood in Spain living under dictator Francisco Franco through her punk days in The Slits and then the Raincoats to her current life as a Christian without a church living on Cape Cod and getting ready to come to Provincetown for the Women’s Week screening of the documentary about The Slits, Here to Be Heard this Thursday. McLardy may be a grandmother, but she has never been one to take sh*t from anyone.

“I hated the idea of someone telling me how I should think,” she says thinking back to her childhood living in a society tightly restricted by its fascist government, with women forced into traditional roles that left little room for her spirited personality to be expressed. She packed up and left for London at 17, did a year of college, and then found her first tribe in the punk scene where her combination of anti-authoritarianism and naivete gave her the freedom she sought.

She recalls, “I came to London with a lot of anger, for one, but also like just a ‘we can do it different, I don’t have to put up with it,’ you know cockiness of being a teenager, feeling invincible, and also like full of hope, you know for what I thought the young people in England represented to me.”

She didn’t start out as a musician, though. Her idea was to do a street show as a mime with some friends. That plan fell apart rather quickly and she found herself playing in a band called the Flowers of Romance with Sid Vicious. But after she rejected Vicious’ sexual advances, she found herself without a group once again. “He did not force me physically, but he wanted to, you know, sleep with me and then I wasn’t interested, so what he did do was kick me out of the band because I wasn’t complying. So then I decided to form my own group with just girls, ‘cause I didn’t want to have to deal with that,” she explains.

In a sense, Vicious did her a favor because that all-girl group turned out to be The Slits. It’s hard to imagine for young women today, but the idea of an all female group of musicians was still a rare thing, and a group that was also led, organized, and entirely controlled by women was unheard of. Women in rock music were largely relegated to roles as singers, often packaged in groups produced and managed by men. Of all the types of music a young woman could be into in the 1970s, punk was certainly the least “ladylike” of them all. So the short-lived career of The Slits was an inspiration to young women everywhere, a reference point for the early 1990s Riot Grrrl post-punk movement, and an example of the ways in which gender roles, (which had already been flouted in the pre-punk New York Dolls), could also be a place of rebellion within punk.

Speaking as someone there in the center of it, McLardy explains, “It’s almost like they were breaking some boundaries, those boys, but there was other things that you know they wouldn’t really tackle. And I thought, we don’t want to do that. I feel like we were a revolution within the revolution, you know? I really feel like we all cried out we want to be who we wanted to be; we don’t want someone to tell us how to be, but that meant very different things for someone like Steve Jones and Johnny Rotten or Paul Cook [of the Sex Pistols], you know, than one of us.”

While The Slits, by any measure, can be seen as feminist icons busting down the doors of the patriarchy within a particular subculture, they didn’t always see themselves as aligned with the larger feminist movement of that time. Again, it came down to independence. “We felt like if we called ourselves ‘feminists,’ the indication was that what we had to do was someone else’s dictate, which was like number one priority, no we don’t want to do that. We don’t know how we’re going to feel tomorrow. We want to be able to have the reins of what we are creating together. Having said that, the values that we had were very much in tune with the feminist movement. We were trying to say to women that you have a place in society, that you have a voice. For many women, like we were invisible! Our only roles were limited to supporting men,” she explains.

Palmolive was kicked out of The Slits in 1978, in part, she says, because she did not want to be managed by Malcolm McLaren, perhaps the most important manager in the punk scene. She eventually found her way to another revolutionary band, The Raincoats, before moving away from music entirely, rejecting that first tribe with whom she connected so deeply. As the documentary illustrates, she went on a spiritual journey, going to India, studying a number of religious possibilities before finding Jesus and later moving to Cape Cod in the 1980s where she attended Victory Chapel in Hyannis for some time before she again found herself searching for something different than what the new tribe provided. It’s a chapter in her life that still seems raw and she feels the need to explain when she is labeled a Christian.

“There’s a lot of Christianity that I hate because they really have gone away from the original intent… the words of Jesus are very different to what Christianity in America looks like. Many times, I have met wonderful Christian people you know, but I have met wonderful atheists, you know! I have had some bad experiences within the church, and I feel like they just made up a lot of stuff, added a lot of this stuff to be in power over people, you know?” she says. “Jesus was inclusive, and he hung out with the prostitutes and the tax collectors, which in that time was like the worst people you could think of, and he came out against the ‘religious’ people. So when you say I’m a Christian, I want to say, ‘well, what do you think a Christian is?’”

McLardy says she no longer belongs to any church because she feels she doesn’t really need a pastor to guide her in her own spirituality. It’s just one more example of her fierce independence, her questioning of authority, and her refusal to be simplified into any one type. She says there is part of her that will always retain the punk ethos. “Just not being afraid to be different is one thing, and also like a sense that really you can do anything if you put your mind to it, that doing things yourself and being connected to what you want to create instead of just following someone’s dictate, is rewarding in a way that a 9 to 5 job which just pays the bills cannot compare. You know, that it’s worth living your life for something that’s meaningful to you,” she says. “There was other things I don’t identify with, like I wrote a whole song about shoplifting, and I think it’s funny, but I don’t feel like [there’s] any truth to it,” she laughs.

Asked what Palmolive would say if she could somehow go back in time and meet her in London in 1978, McLardy laughs and says, “Well it depends how we met. If I have a conversation, I think we will get along really well, but if Palmolive then just saw me in the streets, she was quite judgemental, too, you know. Punk rockers were quite judgemental. If you’d look at someone’s shoes or someone’s hairstyle and say, ‘oh they’re an old fart, and we are the rights ones.’”

Here to Be Heard: The Story of The Slits will be screening at Pilgrim House, 336 Commercial St., Provincetown, on Thursday, October 11 at 3 p.m. Paloma McLardy (“Palmolive”) will participate in a post-screening Q&A. For tickets ($15) and information, call 508.487.6424 or visit pilgrimhouseptown.com.