by Steve Desroches

In that moment of creation an artist never knows how long the work will live. Legacy may not be the point, but nevertheless, each expression represents a point of view, a unique voice that can echo far beyond the life of its creator. The regeneration of imaginative cells is perhaps what some call the inspiration art can produce. Its what makes a painting, a book, or a photograph become part of our collective consciousness throughout generations. Some have a global reach, while others barely dip outside of a tiny village. But no matter. Each artistic work has atomic potential to continue to fly through our culture, creating new universes in its wake.

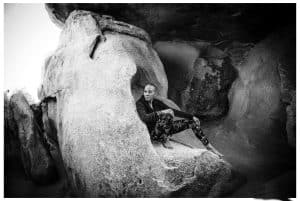

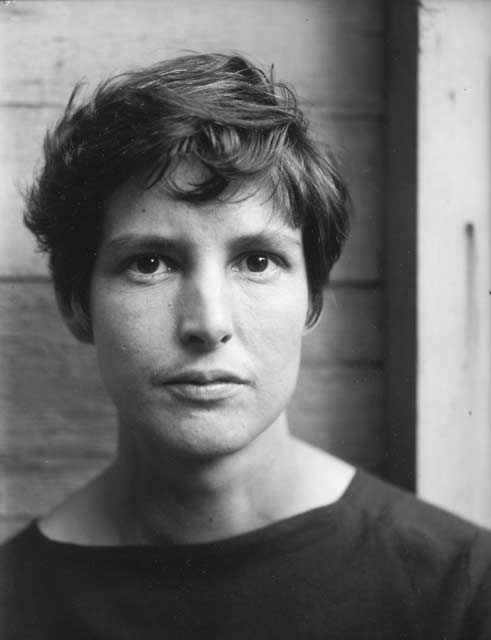

Such an ember drifted all the way from Provincetown to Helsinki via Berlin. Inka Leisma took a year off from her job as a communications specialist for the Finnish Tax Administration to live in the German capital. As Berlin is bursting with creativity, she reveled in the city’s cultural offerings. And it was in 2014 at the exhibition hall Martin-Gropius-Bau, Leisma went to see a major show of work by Walker Evans, the famed American photographer and photojournalist. Prior to traveling to the United States documenting the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration, Evans frequently visited Provincetown, capturing both the town and its bohemian culture. In this extensive presentation of his life’s work there was one photograph that didn’t just catch Leisma’s attention, but rather grabbed a hold of her and refused to let go. It was a portrait of Hazel Hawthorne taken in 1933, most likely in Provincetown. She had never heard of Hawthorne, and the corresponding label didn’t give any information. She was mesmerized. As she rode her bicycle home she repeated to herself, “Hazel Hawthorne. Hazel Hawthorne. Hazel Hawthorne,” so she wouldn’t forget the name. So began a thrilling obsession that brought Leisma to the dunes of Provincetown.

“I still don’t know what happened there,” says Leisma of that day in Berlin. “It defies explanation. Everything turned blurry. It’s very hard to explain. I just really felt like she was reaching out to me. It’s quite emotional.”

A quick Google search later and Leisma had found out the basics, much of which many longtime Provincetown residents remember. Born in 1901, Hawthorne (who later also went by Hazel Hawthorne Werner) first came to Provincetown in 1918 and divided her time between New York and the Cape tip, until she died here in 2000 at the age of 99. Over the course of her fabulous life, Hawthorne accomplished so much more than just sitting for Walker Evans. She was bohemian royalty. A feminist and environmentalist before such terms existed, she eschewed restrictive social conventions and expectations of the day. A cousin of Charles Hawthorne, the artist who founded the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown in 1899, Hazel herself was a major player in the art colony as both a writer and doyenne of the salon and artistic social circles in town. She eventually came to own Thalassa and Euphoria, two of the famed dune shacks where she wrote and entertained such writers as ee cummings and Jack Kerouac (some critics claim Hawthorne was an early influence on the Beat writers). Everyone knew her.

As Leisma dug into researching more and more, she learned it wasn’t just Hawthorne’s joie de vivre that made her so popular, but also her work, which attracted the high praise of her fellow writers like Edmund Wilson, John Dos Passos, and John Cheever. However, as is so often the case with women, she ended up a mere footnote in the biographies of her famous male counterparts. Her two novels, 1934’s Salt House, a fictionalized account of life on the Cape tip, and Three Women, published four years later, are long out of print and very hard to find. She not only wrote for Provincetown newspapers and magazines, but also The New Yorker as well as highly esteemed literary and poetry journals that published her many poems, essays, and short stories. The more Leisma learned, the more it troubled her that Hawthorne was being lost to history as memory of her and her work began to fade, even in the town where she once held court as the Queen of the Dunes. She became committed to ensuring Hawthorne’s like and work would not vanish. And her journey of discovery has been a remarkable one.

“You never know what’s around the corner,” says Leisma. “But you have to go because it’s so very good.”

After connecting with several relatives of Hawthorne’s via Instagram, Leisma first traveled to Provincetown in 2017 as well as to other locations in the United States, delving into archives large and small, including the famed Beinecke Library at Yale University, the New York Public Library, and Provincetown’s own public library. She returned in 2018 after securing a spot with the Peaked Hill Trust Residency Program for the Arts and Sciences to spend a week in the same dunes where Hawthorne once lived and wrote. Her project’s initial results are on her website: findinghazelhawthorne.com, but she’s also finished the first draft of a narrative nonfiction book about her global trek to present Hazel Hawthorne to the world. Funded in part by a grant from the Association of Finnish Non-Fiction Writers, her manuscript tops off at about 530 pages. Written in English, her goal is to have it published first in the United States.

Leisma rattles off details about Provincetown like a longtime visitor, proof she is a quick study and keen observer. Prior to seeing the portrait of Hawthorne, she had never even heard of Provincetown. Now, she is smitten, as when she sees the ocean in Finland she envisions the waves lapping on the beaches of Provincetown on the other side of the Atlantic. The town, and its people, were so wonderful to her, friendly and helpful with her work, inviting her into their homes to answer any questions she had and to wish her well. But it was those times in the dune shack that for her are the biggest gift of this project, fueled by the image of Hawthorne that spoke to her five years ago.

“It was as really magical as it sounds,” says Leisma. “Getting up when the sun rises and going to bed when it sets. Reading original documents, reading her work in the same place she lived. It was just magical.”

To learn more about Inka Leisma’s project visit findinghazelhawthorne.com.