Alex Kotlowitz Comes to the Hawthorne Barn

by Steve Desroches

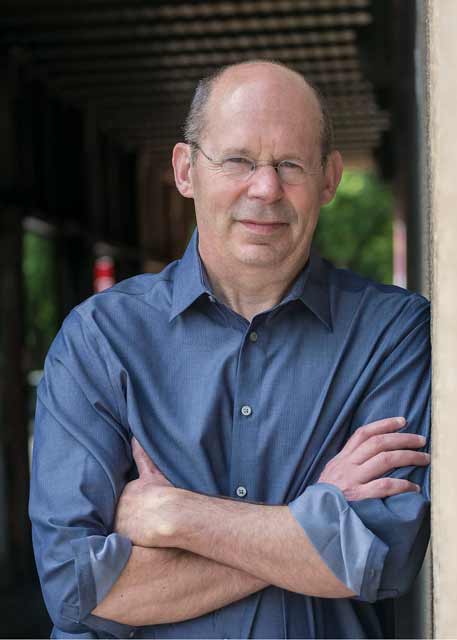

In 1991 journalist Alex Kotlowitz’ book There Are No Children Here became a national bestseller. The nonfiction narrative—with the subtitle The Story of Two Boys Growing Up in the Other America—introduced the country to Lafayette and Pharoah, two young boys growing up in Henry Horner Homes, a public housing project in Chicago. It chronicled in heartbreaking detail the violence these two children witnessed as their mother tried to protect them from the drugs and gangs endemic to the neighborhood in a city that often ignored the plight of its most vulnerable residents. The book sparked a nationwide discussion of poverty, racism, gun violence, and drug laws to such a degree the New York Public Library named it one of the 150 most important books of the twentieth century. Since then, Kotlowitz has become one of the most respect reporters on youth, violence, and poverty in the country, and he’ll be in Provincetown this Saturday night at the invitation of Twenty Summers at the Hawthorne Barn, where he’ll be in conversation with Adam Moss, the former editor-in-chief of New York magazine.

A professor at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, Kotlowitz’ latest book, An American Summer: Love and Death in Chicago, documents one season in one of the great cities of America, one that is plagued by violence. In the past 20 years, over 14,000 people in Chicago have been killed and another 60,000 wounded by gunfire. He explores how that affects individuals and neighborhoods, providing both a micro and macro perspective of the third most populous city in the country. While many major American cities have seen a decline in violent crime, Chicago’s statistics remain stubbornly persistent, something that has become a frequent topic of national news media as well as a politicized point among elected officials and 24-hour cable news networks. The city certainly has deep problems, but in part becomes caricatured as the public discussion often lacks nuance or notes of progress.

“It becomes part of the issue in that it’s become the reputation of the city,” says Kotlowitz. “This is a great city. I’m from New York originally, but I’ve fallen in love with Chicago.”

Statistically, Chicago is not in the top ten most violent cities in America, with Baltimore, Detroit, and St. Louis all ranking higher, says Kotlowitz. But he offers that point only for accuracy, not a deflection of the very real issues in Chicago. One of the reasons that violence continues at such levels is that Chicago is “profoundly segregated,” says Kotlowitz. One can visit Chicago and see a booming, modern city that appears peaceful, prosperous, and safe. Those neighborhoods that are not are, for all intents and purposes, walled off, keeping them stuck in a mire of desperation and hopelessness. And violence. Research shows, and Kotlowitz’ reporting confirms, that the residents of these neighborhoods show the same rates of post traumatic stress disorder as returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan. The same issues of mental health and self-medicating follow, making this very much a public health issue.

As much of his work has focused on violence and youth, Kotlowitz notes the disparity in the way gun violence and children are both reported on and discussed in the public arena. School shootings like those at Columbine, Sandy Hook, and Parkland dominate headlines for obvious reasons. But for decades, children in poor neighborhoods in which the residents are largely people of color have been seeing the same sort of violence, be it in the schools, parks, streets, or apartment buildings. The stress and trauma of sending your child out the door into a neighborhood where shootings are common is daily life for these parents. But it doesn’t get the same coverage or the same attention when we as a nation look for solutions.

“We don’t ask the questions in the cases of a city when the violence is almost routine,” says Kotlowitz.

Kotlowitz began his career at a small alternative weekly in Lansing, Michigan, but also did some work for Michael Moore’s magazine The Flint Voice (later known as The Michigan Voice). Most recently, Flint has been in the news for its ongoing public health crisis due to its contaminated water supply and failing infrastructure. But when Kotlowitz arrived, Flint was just on the precipice of collapse, a phenomenon that went into free-fall when General Motors left the city. It gave him an opportunity to carefully observe the decline of a once prosperous, safe, middle-class city to one with a high crime rate, drowning in economic stagnation and neglect.

As a reporter, Kotlowitz is drawn to people on the margins, as that is a good way to measure the health of a society, he says. The most persistent myth he’s seen over his career is that poor people and their respective communities are somehow responsible for their situation. That somehow it’s due to a character flaw rather than a dereliction of government and society to maintain a collective well being for all. A similar myth persists for those killed by gun violence in poor and black neighborhoods, often cast as somehow responsible for their own deaths. Kotlowitz’ work has doggedly told stories of those living in such neighborhoods to dismantle the elitist and racist distortions and has given the residents a fuller voice and the reader an outlet to a three-dimensional humanity of our fellow Americans.

As bleak as the story of Chicago can sound, Kotlowitz is optimistic. There are good things happening in the city, and he’s encouraged by the election of Lori Lightfoot as mayor, who took office on May 20, describing her as “tough.” His next book, A Walk In Chicago: Never A City So Real, comes out in June and is part of the same literary travel series in which Michael Cunningham wrote Land’s End: A Walk In Provincetown, where writers write about places they love.

“I’m a storyteller,” says Kotlowitz. “It’s what I love to do. A good narrative asks questions rather than answers them. And in this time when everyone seems to be screaming, a good story allows you to find your own way. You’re on your own when you read a story. You figure it out for yourself.”

Alex Kotlowitz and Adam Moss in Conversation is presented by Twenty Summers at the Hawthorne Barn, 29 Upper Miller Hill Rd., Provincetown, on Saturday, May 25 at 7 p.m. Tickets are $30 and are available at 20summers.org. For more information call 508.812.0278.