by Rebecca M. Alvin

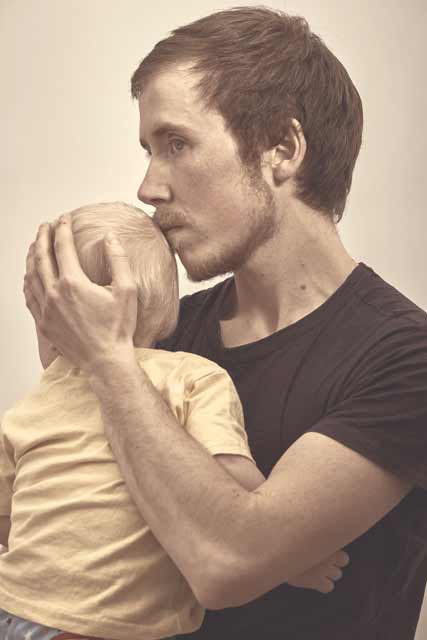

Jeanie Finlay’s new documentary Seahorse opens with the titular sea creature cavorting underwater, setting the stage for what is a very naturalistic film about one of the most natural aspects of humanity: the desire to have a biological child.

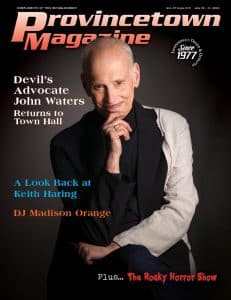

The fact that the subject of the documentary, Freddie McConnell, is a transgender man who wanted to conceive and carry a child may be the aspect that brings attention to the film, however McConnell insists his “transness” is not really as relevant as it might seem to the largely cisgender audience. Just hours before the film’s world premiere this past April in New York at the Tribeca Film Festival, Finlay and McConnell sat down to talk with me about the film, which now makes its way to Provincetown for two screenings in our annual film festival this week.

Provincetown Magazine: Obviously the film has this nature footage and it’s all very much natural world, and I wondered what your motivation was behind that?

Jeanie Finlay: I made a lot of the film on my own and when I was going down to Deal [England] to stay with Freddie, there’s a really beautiful coastline, so I used to run every morning at dawn… and would just meditate on the film. I sort of believe as a filmmaker, that the film suggests the way to tell it to you. So I would just think about what I’d learned from Freddie, how I was feeling, and I felt like the film is about time, changing of time. The seasons and the landscape of Deal is informative. We’re on the edge of England, and it just felt really strong to me to include the natural world, because having a family is the most natural thing in the world. And the images, they just felt like the right fit. So I filmed what I dreamed about, I filmed what I thought about. I filmed what I saw.

Photo: Manuel Vazquez

PM: There’s a point in the film, Freddie, where you say something about not wanting to make the pregnancy “public,” and it was sort of ironic because I’m watching you in a documentary. Did you struggle with that?

Freddie McConnell: It’s just a very deliberate timeline. So, again, I always knew when I set out to share the story, I wanted to do it on my terms. So often when a trans person shares something about their life publicly, it’s not on their terms in any way, and one of the important things for me was that this film would come out considerably after my experience of actually being pregnant, when I’m sort of back in my normal routine and normal life and I’ve been able to focus entirely on being a dad for the the first little bit. So, at the time, the way the film was made was very locked down and secret. My colleagues didn’t know. That was just sort of a personal thing. I knew I needed to stay healthy and on top of things, and I didn’t want to become a tabloid story. The way that these stories are told in the past is usually very exploitative and sensationalizing. So that was very deliberate.

PM: So there must have been an added pressure for you, Jeanie, that this is a very sensitive subject people don’t even have the right language to talk about.

JF: Making films is hard! It’s always hard! Making films is always challenging, but I thrive and embrace the challenge. I want to learn things. It’s very unusual for me to make a film where I’m invited… because usually I go out and find my story, track down the access, and make that happen. So this was a really different prospect. But the reason I said yes, was that when I met Freddie and talked to him about it, it was sort of like this mysterious stretch of time in front of us. It was risky. No one knew what was going to happen. Would Freddie be able to get pregnant? Could he get pregnant? What would happen? Could I document it? And actually, could I be there at the birth, and things like that. So, I think at these first meetings I felt a connection, a chemistry. I thought we were really different in a refreshing and interesting way, and I had so many questions that it made me feel really strongly that I’d like to make this.

PM: I think when people talk about transgender issues and transgender people, there’s a faction of people who just don’t accept it, but among people who are accepting, I think they often want to talk about it in very philosophical, theoretical way. And it seems like in the film there’s a couple of places where those conversations come up. Is that something you’re comfortable with doing?

FM: I suppose that there is a certain irony there because certainly my motivation for sharing the story in this way is to try to provide an alternative to having those kind of “debates,” or making it philosophical, because actually I think that’s what happens… People who are trans who are trying to help other people understand are trying to put into words something that’s fundamentally indescribable; that creates this huge empathy gap. And so, by having a film like this, you could sit in the cinema or in a darkened living room somewhere you feel safe and watch an experience that on the surface might seem really unusual and alien to your own experience, but then come away thinking, “oh well I can relate to that particular moment or that particular feeling, or I can relate to the mom in this, you know, my mom. Or you come away from it not thinking that all of your questions and all of your confusions have been totally solved, but perhaps that they’re not as important as you thought they were. And now that you have a deeper connection on an emotional level, perhaps akin to a connection you’d have with a friend where certain things just don’t matter if you care about the person, that kind of thing. That’s kind of what I wanted to create. So, I’m really happy to talk about that particular kind of dynamic, which I think comes from that human need to understand and to simplify and to make things black and white. And actually, what we need to do in these kinds of situations is just to accept that they’re really complicated and messy and hard — possibly impossible—to understand, so let’s just try to create empathy and try find the common ground. And I hope that’s what this film does.

PM: Many people when they are pregnant, their relationship to their parents changes. Did you find that your relationship with your mother or both parents changed?

FM: Yeah. I would say I was taken aback by how difficult I found pregnancy and that my mom stepped up and was incredible throughout, and I’ll never be able to repay her for that sort of support she showed me… And, ultimately, I think a new baby in any family, even with all the challenges that might exist and all the kind of baggage and history and that kind of thing, ultimately brings people together, and that’s been my experience, as well.

PM: Another part of that is, you also, after you have a child, you think a lot about your own childhood, and in the film you go through a box of memories. I imagine that would have been difficult to —I think you even say it in the film—to be “confronted with your dead name.” Do you feel more open?

FM: It’s an interesting question… I don’t actually struggle with looking into the past, I never really have. I keep all that stuff because I love it and I find nostalgia almost painfully poignant. But then again I think that’s quite a universal experience. It’s sort of this weird tension, it’s almost too much to look at, but my discomfort in those situations, and I think that was quite early on in the filmmaking process that we looked through that trunk. It was a fear that [we were] getting into territory that is often a point at which a film or a TV show about a trans person encounters tropes and cliches, and I worried, “Am I going be able to —this is a moment of truth almost, or a testing ground for what are we going to do with this film, what kind of story are we telling?” It was when our trust was still forming, and I was nervous that if I say my dead name or if there’s stuff that I feel —I’m comfortable with it, but it’s private and it’s not relevant—those sort of conversations that often don’t get had when it comes to telling a trans story. It’s just assumed you’ll cover this and you’ll cover this and you’ll show this. So, that’s where the discomfort comes from. It’s not my personal discomfort, it’s kind of like, can we tell the story in a different way?

PM: The film looks at your journey of pregnancy, but now you have like a year of being a parent. Would you share a little bit about what that’s been like?

FM: You know what, I won’t. It’s wonderful. It’s wonderful and we’re having a great time, but going into it this was another boundary that I had. This is my story of becoming a parent; it’s not my story of being a parent, and I don’t want to overstep any boundaries that my son might have when he gets older, anything that he can’t consent to actively that identifies him, or that begins to tell his story, I don’t think that’s fair.

PM: Would you do it again?

FM: The dreaded question. (laughs) I’m not taking anything off the table.

Seahorse is screening in the Provincetown International Film Festival Thursday, June 13, 12 p.m. and Friday, June 14, 10 p.m. For venues, full festival information, and tickets, visit provincetownfilm.org.