by Lee Roscoe

Marla Rice says that the four “powerhouse” artists who comprise her Rice Polak Gallery’s current show have “works which complement and connect to each other,” though they each have different mediums, styles, and content.

Layered photographs by Susan Mikula entitled The Interdicted Land worked from Polaroids or constructed from distressed film, shot using vintage cameras, complement the layers of Deb Goldstein’s intricate collages. Both conjure mystery, are not instantly accessible, take time to contemplate.

Willie Little works in two modes. There’s a series of “Nodder Dolls” with political themes, for instance a bobble headed baby Lady Liberty rocks above a slice of watermelon and a collection of Klan Confederate flags. Then there’s a group of paintings entitled Crossroads, made using metal particles, wax, and paint on wood, which he scrapes down and allows to rust for a time, literally, before setting them. This technique of oxidization is uniquely his.

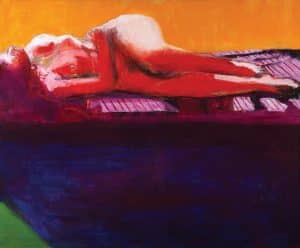

Little’s work complements René Romero Schuler’s thick layers of textured oil worked with brush and palette knife—out of which constrained female figures emerge. Are they joyful, or trapped by time and fashion? It’s up to the viewer. Similarly, Little’s abstractions intentionally reminisce on the South of black tenant farmers’ old buildings, but may evoke entirely other responses in the observer.

Schuler’s second grouping, wire figures of women, like Little’s dolls, explore self-image, in part pride lost and gained.

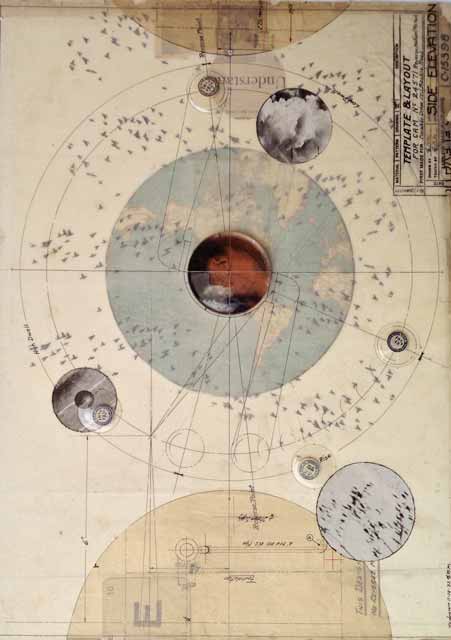

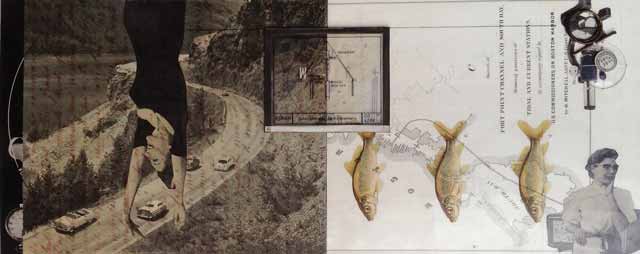

Rice usually hangs exhibits, but this time, one artist, Goldstein, will hang her “collage of collages,” as an installation according to a vision she has—ordering in sequence images she occasionally repeats, such as eggs or birds, which carry from one piece to the next. “My studio is like a landscape. If there’s something in my sight I will use it” and reuse it, cutting a part of an image for one piece and using the rest for another, she explains. Selecting from “paper ephemera, old newspapers, 19th-century letters with beautiful script from Italy, Iceland, France, magazines, (Life magazines are great), engineering diagrams, weather reports, street maps from the early 20th century,” it’s the foxing and heft of the paper which inspires her. “The paper has to have had another life from another time for me to use it,” she says.

She’s “petrified of color. It’s too complicated.” Instead she prefers the “variance of tone” of old paper, the monochromes and subtle contrasts that “create memory” and are dreamlike.

Starting with a central image, idea, character, or object, Goldstein says, “It’s like writing a story. The characters, or plot, take on a life of their own.” You may control it to a certain extent, but the tale begins to tell itself as “you find and hunt for the next piece.” So no, she does not know exactly where any piece will eventually take her. “It takes on a life of its own,” she says. “I have a lot of objects in my studio. I’m a scavenger. I look down and say here’s this rusty nail washer which will go beautifully into my piece. Once placed there it changes the piece symbolically, metaphorically, integrating into the piece so that it is no longer a rusty nail per se, but takes on a different meaning” as it moves the collage forward, enhancing it.

There are lenses in all her pieces: film, optical, watch crystals. There’s also always an “A” for her mother Anne, who was “an amazing painter, a watercolorist. She was a seamstress. She made incredible things for people. If I needed a couch, here’s a couch.”

As a child Goldstein herself drew and put things together, recalling fondly old-fashioned Lego blocks as “the ancient Legos of Mesopatamia.” She continued doing art through high school, college, and a number of art schools and workshops, such as a seminal one with collagist Jonathan Talbot. But she’s mainly “self-taught in terms of collage. By observing, reading, accumulating knowledge, looking at other people’s work,” her own competence grows. “I’m so proud of this show. It’s an evolution of my work.”

Joseph Cornell, pioneer of assemblage, and sculptor and collagist Lenore Tawney are particularly strong influences, but Goldstein wants her own voice. “Every artist struggles with that; you look at another’s work, are attracted to an image, method, style, or composition, and strive to translate those into one’s own interpretation, so people will say, ‘yes that’s a piece by Deb.’”

“You know when it works.” And when it does the result creates a wow moment for her, thus, Astonished Discoveries is the title of the show. There are 14 pieces. The smallest is 9”x9” and the largest is 21” x 15”.

The title piece itself contrasts light and dark with a curved road echoed in an old map of Boston Harbor. There’s a balance of curves, contrasted with a photo of a woman upside down and some fishes, just for the aesthetics. A scientific slide holds the contrasts together. A depicted microscope implies the theme of the title. There’s an Alice in Wonderland feel to the piece. No Fear of Flying uses an engineering drawing, birds, and pieces of maps, some seen through a watch crystal, combined with a card from an African game. A transparency of a hand in the midst of this is a comment on the art maker’s role. “I’m perceiving into the piece,” Goldstein says artfully, adding, “It’s about revolution, (the motion of circles), the sweep of your eye. A bird’s eye view.”

“In collage, the equation is one plus one equal three. It takes disparate images and objects to create something totally different in terms of idea and concept. The end result transforms the meaning and the composition…creates a transformative image, perspective, visual perception. It’s like living, life itself,” Goldstein says, “when certain things converge,” similar clarity occurs.

While she may, as the artist, receive that revelatory twist, that sum of the whole greater than the parts, what about the observer? She hopes each piece tells a story which the viewer may interpret in an entirely different way, according to their own vision. In order to get there, however, she cautions, “I have very small details you must come up close to see; then you have to back away to fully get it.”

An exhibition of works by Deb Goldstein, Willie Little, Susan Mikula, and René Romero Schuler is on view at Rice Polak Gallery, 430 Commercial St., Provincetown, through August 14. For more information call 508.487.1052 or visit ricepolakgallery.com.