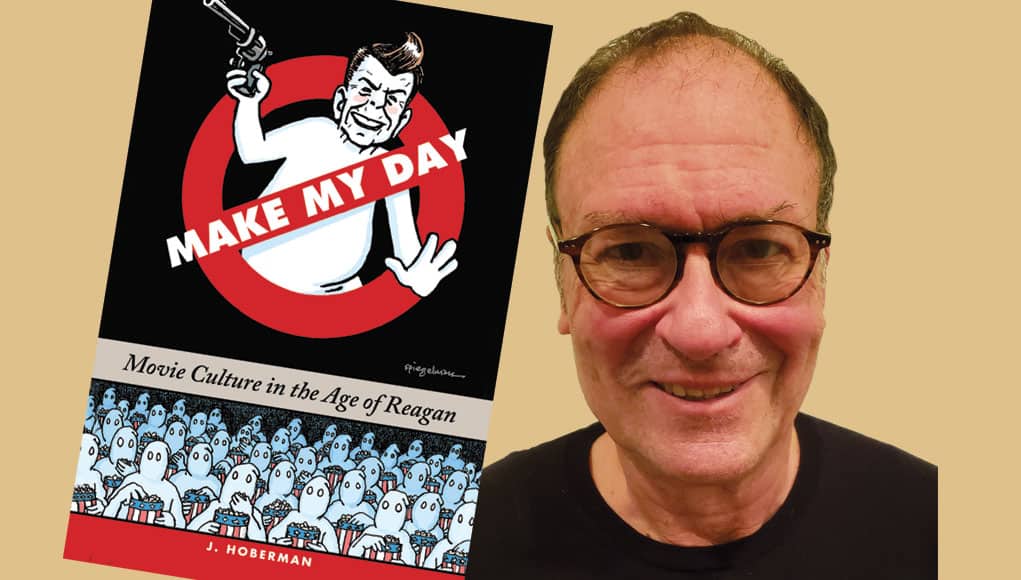

Reagan, Spielberg, and J. Hoberman’s Take on 1980s Cinema

by Rebecca M. Alvin

There’s a scene in the 1985 film Back to the Future where Marty (Michael J. Fox) has gone back in time to the 1950s and is trying to convince Dr. Brown (Christopher Llloyd) that time travel is real and that the doctor himself invented a time machine in the future. Incredulous at the suggestion, Dr. Brown asks Marty questions about the future as a test. He asks, “Who’s the president?” Marty replies “Ronald Reagan,” to which the doctor responds, “The actor? Then who’s the Vice President, Jerry Lewis?” It’s a joke that resonated at the time and still does today as it once seemed utterly ridiculous that the star of Bedtime for Bonzo could become the leader of the Free World. In writer J. Hoberman’s new book Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan, this film as well as others made between 1975 and 1989 are discussed within the context of the times in which they were made, all more or less connecting with the ascendance of Ronald Reagan and his brand of Republican politics.

“My sense of Reagan is that he really was the culmination of Hollywood,” Hoberman says. “Hollywood movies were made for the whole world, a kind of universalist credo which was largely commercial but also had a kind of idealistic component, too, so I think that Reagan embodies that. And it’s not like he even had to think about it, he internalized that… He was able to give this illusion of goodwill and optimism, which I think is something I believe he trafficked in, in a general sense.”

In film circles, Hoberman is well known as a key film critic who wrote for arguably the most important alternative newspaper in the U.S. before it stopped publishing last year, The Village Voice, for over 30 years and succeeded Andrew Sarris there as the lead film critic back in 1988. In addition, he’s written roughly a dozen books on film, including a key text of cult movies co-authored with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Midnight Movies. He’ll be in Provincetown reading from Make My Day at East End Books Ptown this Thursday evening.

Reflecting now on the films he’d originally seen and written about when they came out in the 1980s, Hoberman says for the most part, his opinions have not changed. “When I revisited the movies of the period, I don’t think there are any that I liked any better now,” he says. “And in terms of Reagan, I kind of realized that he was a more complicated figure than I had given him credit for at the time.” He’s quick to add that his dislike for Reagan has not softened, but writing the book has given him more perspective on the complexity of Reagan as a cultural icon and political leader.

In Make My Day, Hoberman takes quite seriously an era in movie history that many might see as simply escapist, blockbuster-driven, and ultimately meaningless. But in Hoberman’s position reviewing these films at the time they were released and with the benefit of being a mature moviegoer, rather than a child or teenager (which is who many of these movies were made for), he is able to put them in the context of the times, often reprinting and annotating in some cases his original writings from The Voice. While many of us who were in that targeted demographic in the 1980s might have thought of the Indiana Jones movies as escapist nonsense that made us all want to be archaeologists (a job that seemed to be the height of adventure and not an academic field involving patiently and carefully uncovering relics of the past and writing about them), Hoberman saw the undercurrents of racism and retrograde attitudes that permeated these films. We’ve all had that experience of revisiting films from our youth only to find that they are actually racist, sexist, homophobic, and morally bankrupt, ruining the phony nostalgia we had for them in our minds. Writing about Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom upon its release in 1984, Hoberman writes he “lost it” and then reprints the review, which states, in part:

“[Indiana Jones] is inordinately racist and sexist, even by Hollywood standards. There’s a kind of willful ignorance here, as though the magnitude of their success exempts Lucas and Spielberg from any moral considerations. Like white boys just want to have fun! As the film’s only woman, Capshaw is compelled to play a bitchy gold digger (her desire for fortune implies no glory) who takes her ritual lumps toppling backward off elephants, being terrorized by jungle animals (while the boys argue over cards) or yo-yoing up and down above the Sacred Lava Pit while wrapped in the embrace of the hero’s equally fetishized whip.

“Remaking the 40-year-old pulp serials they adore—without, apparently, pondering what it is that fascinated them so—these new Kings of the Earth have no qualms about reproducing 40-year-old assumptions as well.”

Much of the book focuses on the illusions propagated by Ronald Reagan and eagerly embraced by the culture at large. The nostalgia for the 1950s (exemplified in 1970s and 80s films Grease, Peggy Sue Got Married, American Graffiti, and Back to the Future) is directly connected to Reagan’s appeal. Hoberman writes in such a way that films are discussed right along with the actual historical events going on during their production and release, which does make the point that regardless of what intentions may have been, these films come out of a certain climate and reflect that.

Hoberman says he began writing the book early in Obama’s first presidency and was still writing when Trump became president so he was thinking about Trump all the time. It’s easy to draw parallels between Reagan, the movie star president, and Trump, the reality TV president, but Hoberman sees them as distinct in a number of ways.

“Trump comes from a completely different media ecology. I mean he wasn’t a movie star, he established himself as a tabloid celebrity first and then was able to reinvent himself, or actually save his career in a way by becoming a television personality, not just on reality TV … there was wrestling and so on. And those are not consensus-building activities. Something else is going on there,” he says.

Looking at the movies today and how they may reflect the same zeitgeist that brought Trump and various other Right-wing leaders around the world to power is a book for another day. Hoberman says he now considers himself “a recovering film critic,” because at 70 years old he doesn’t see too many movies anymore. He continues to write about film and culture for various publications, including The New York Times. Asked if he misses writing for The Village Voice, which for many was the paper of record for alternative culture, he laments not being able to work with the great, talented people he worked with there. “It was much more fun to write for the Voice because, you know, I do a fair amount of writing for the Times, and there’s so many things you can’t do and you can’t say, and at The Voice I was really free to do whatever I wanted and that’s really rare.”

J. Hoberman will be reading from his new book Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan at East End Books Ptown, 389 Commercial St., on Thursday, August 15 at 7 p.m. For more information call 508.413.9059 or visit eastendbooksptown.com.