How the Swedish Nightingale Swooped on to the Outer Cape

by Steve Desroches

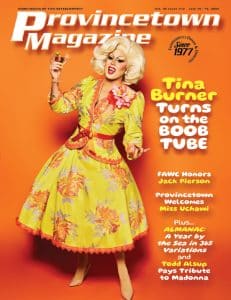

TOP IMAGE: Jenny Lind Tower in North Truro

Truro has gorgeous beaches, sweeping landscapes, and thick wooded areas, all of which help maintain its reputation as the last rural town on Cape Cod. While its natural environment may be the biggest draw for the tiny town, it does have historic buildings like Truro Town Hall, Cobb Memorial Library, Highland House, and of course Highland Light, a quintessentially Cape Cod lighthouse. But Truro is also home to one of the region’s most peculiar oddities – the Jenny Lind Tower.

You never really forget the first time you see the Jenny Lind Tower, as it seemingly comes out of nowhere and it looks so out of place, like a rook on a chessboard shooting out of the thick vegetation that surrounds it. There’s no road to it nor is there really any footpath. Most notice it from a distance when playing golf at Highland Links or if they go for a long stroll before seeing a concert at the Payomet Performing Arts Center, as its located between Highland Light and the old North Truro Air Force Station. It’s like a medieval castle from a Hollywood movie, so much so you expect a dragon to swoop by or Rapunzel to toss her long hair from its peak. It looks completely out of place for Cape Cod. So what exactly is it doing there?

“Yeah, well, we’re not sure,” says Bill Burke, historian and cultural resource manager for the Cape Cod National Seashore. “That’s where the rub is, isn’t it?”

It’s known how it got there, just not really why. The stone tower was originally part of the Fitchburg Railroad Depot on Causeway Street in Boston, and appropriately enough was built out of Fitchburg granite in 1848. After a fire in 1925, the station was torn down in 1927, which is when one of the turrets from the front faзade was moved from Boston to North Truro by Henry M. Aldrich, who was a lawyer who, like his father, worked for the railroad industry. It took two months and five men to complete the reconstruction of the 260-ton structure, though the original tower was 90 feet, so it was significantly shorter at 55 feet as it was not rebuilt in its entirety, says Burke.

Aldrich owned significant amounts of land in Provincetown and Truro, and once the tower was moved, he built five small cottages around for his family, which long ago were torn down. But why would he go through the time and expense? It seems a terrific eccentricity even for the Outer Cape, which long before Aldrich and to this day revels in its offbeat culture. Burke says the conventional wisdom and the most likely explanation is that Aldrich moved the tower in some sort of honorific for his family’s connection to the railroad and a bit of an honorarium for the beautiful train station that met the wrecking ball. The only documented use of the tower is when Aldrich and his family watched the total solar eclipse of August 1932 from the top. But it’s the connection to one of the biggest figures of 19th century pop culture that give the tower both its name and its mythology.

The Fitchburg Railroad Depot featured an auditorium in its top floor that at the time was the largest in Boston, with 1,500 seats and additional room for 300 to stand. It hosted the biggest acts and shows of the day, so when the famed Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind embarked on her first American tour in 1850 it was certain she’d play the venue. Already a major star in Europe, none other than P.T. Barnum smelled both money and his beloved media attention when he read what a star Lind was and how she sold out concert halls throughout the continent. He booked her for a 92-date tour without even hearing her sing a note. A showman at heart, Barnum knew how to attract publicity. He frequently and purposely oversold his shows to create an air of excitement as the crowds elbowed their way into venues and circus tents around the country. Such was the case when Lind played Boston, but on one particular night, angry ticket holders stuck outside began to riot, breaking windows and fans of the “Swedish Nightingale,” as she was known, and stormed the venue. A persistent myth, most likely started by Barnum, but with no documentation in any newspapers of the day, says that Lind took to one of the towers of the train station and sang, soothing the angry crowd. Thus her name’s attachment to the tower in Truro. And it’s become one of the most frequently asked about features of the 44,000-acre Cape Cod National Seashore.

“It’s a common question,” says Burke from his office at the Salt Pond Visitor Center in Eastham. “It’s one of those questions you get tired of as, after all, it’s such a long answer.”

That Lind’s fame would continue to echo in our culture is no surprise, as relative to today’s pop stars she was more famous than Lady Gaga and Beyoncй combined. And it was not just for her voice. Lind was as generous as she was wealthy. She gave most of the proceeds from her American tour to charities in her native Sweden and throughout North America. So it’s no wonder the name Jenny Lind is ubiquitous throughout the U.S. and Canada, including the towns of Jenny Lind, California and Arkansas, a large island in the Canadian territory of Nunavut, on schools and churches she helped build, and on streets signs nationwide, including Jenny Lind streets here in the Massachusetts cities of New Bedford and Taunton. She appeared in fictionalized form in the 1980 Broadway musical Barnum as well as the smash hit 2017 musical film The Greatest Showman.

This curious tower in Truro however stands as the most mysterious monument to the Swedish Nightingale and has intertwined itself with local lore, becoming a Cape Cod ghost story. That area of the Outer Cape is thought to be haunted by the ghost of Goody Hallett in a Hell-hath-no-fury phantom tale where she screams like a banshee cursing former lover Samuel Bellamy, pirate captain of the doomed ship Whydah, which sank in 1717. The cries, according to sailor’s tales, caused ships to sink in those dangerous waters off the coast, but ever since the tower went up the ghost of Jenny Lind calms the seas as she sings over Goody Hallett’s wicked shrieks. It is a surprise that the tower itself did not meet its demise when the property became part of the Cape Cod National Seashore in 1961 as the National Park Service mission then was to return the land to its natural state, tearing down many structures within the newly created park.

“It was probably too hard,” says Burke as to why the tower was not demolished. “It’s kind of in limbo. We’ve never formally evaluated it. It’s never been documented or studied. It’s not on the National Register of Historic Places. It would be the National Park Service that would do the process to put it on the register, but if someone else wants to we’d be fine with that. I’m not sure what else there is to learn about it. There’s a very small population that are really into that tower. A lot of them are railroad history buffs. Its just one of those oddities.”