by Steve Desroches

Top Image: The Mary Heaton Vorse House Photo: Tony Luong

“Our houses are our biographies, the stories of our defeats and victories.” – Mary Heaton Vorse

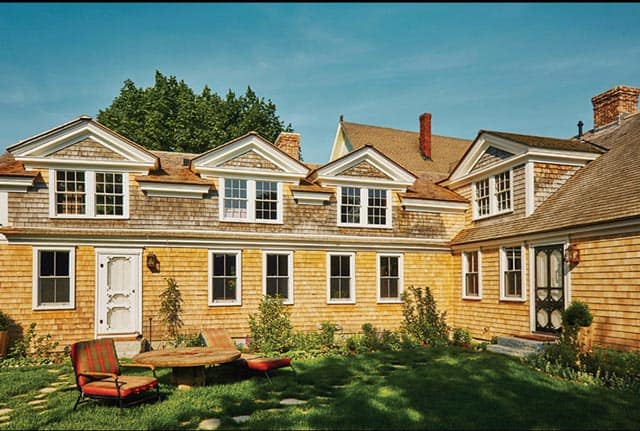

Mary Heaton Vorse fell under Provincetown’s spell as soon as she saw the little spit of sand rise out of the sea as she approached the town aboard a steamship from Boston in 1906. She was vacationing with her husband Albert Vorse, a journalist who encouraged her to explore a writing life after she floundered as an artist. After taking in the town on a horse-drawn carriage, Vorse knew she’d never leave. Born to a wealthy family in New York City, she’d seen much of the world, but nowhere compared to Provincetown. The next year, the couple purchased the Captain Kibbe Cook house, home to the famed whaling captain who had died two years before. Drawn to the house’s crooked shutters and coastal New England patina, Vorse knew it was to be her home, as she’d always wanted to live in an old house. And it would be her home until she died at the age of 92 in that house in June of 1966.

It was more than just a home to Vorse and her family, though. Her career shift from artist to writer proved wise, as she became a celebrated journalist, known at the time for her radical writing on feminism, civil rights, pacifism, socialism, and perhaps what she is best known for, the rights of the worker. In 1912 she famously covered a textile worker strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, as well as many other labor strikes throughout the country, at times becoming a target of violence to those opposed to organized labor attempting to prevent her from publishing her accounts. To say she was a woman ahead of her time seems trite. Rather, she was a woman who knew her power and took it.

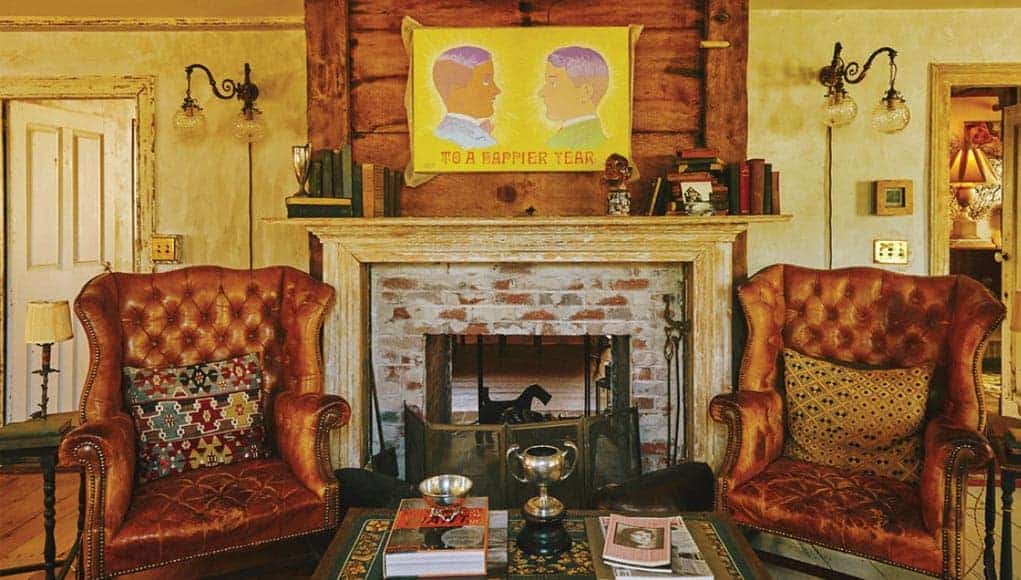

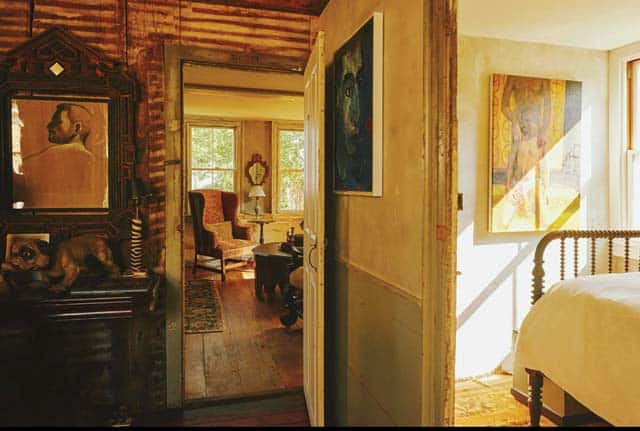

Over the course of her career she wrote over 400 magazine articles and 16 books, including her 1942 title Time and the Town: A Provincetown Chronicle, to date largely considered to be the standard bearing text of the town and its history. But through writing about the town Vorse wrote in part a memoir, too. As Harvard University English professor Daniel Aaron wrote in the foreword for the 1991 edition of Time and the Town, the book is about many things, but “most of all it is the biography of the house she bought in 1907.” It was there that she was a cultural maestro, hosting literary luminaries like Eugene O’Neill and Edna St. Vincent Millay. It was in there, around her big wooden table, that the Provincetown Players gathered to talk about their new, radical theater company. And it’s where communist activists John Reed and Louise Bryant debated the politics of the day before heading to Russia to bear witness to the Russian Revolution. That house at 466 Commercial Street was for decades a home to an important hive of radical, liberal thought and art. It’s why when it came up for sale, famed designer Ken Fulk just had to buy it.

“People talk about old Provincetown,” says Fulk. “To me that concept is in the bones of that house. I couldn’t bear the thought of what would happen to that house when someone would go in and tear it apart and put in granite countertops. It would erase what the house means, what happened in there. My goal is to maintain the legacy she started.”

Fulk has been a part of Provincetown for over 30 years now. And he spends most of his time here when he’s not traveling the world working on design projects, his most recent gig being a commission to redesign the Cloud Club in New York’s iconic Chrysler Building. Locally, he’s done design work at the Crown and Anchor, Liz’s Café, and the Commons, as well as an historic renovation of George Bryant’s former home where Fulk and his husband Kurt Wooton now live. But it’s not just his aesthetic that has the world paying attention to Fulk’s work; it’s his ethos, too. When he transformed St. Joseph Church in San Francisco, turning the 1913 National Historical Landmark into the St. Joseph’s Art Society, he grabbed global attention. The cathedral had been empty for 30 years. Fulk saved it and, in the process, gave San Francisco a new arts center. That kind of phenomenon is often the stuff of dreams when a community is faced with a beloved historic building in decline. The model for St. Joseph’s is in part what his vision is for the Mary Heaton Vorse House.

With the renovation complete, plans for events at the house were mostly put on hold due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Several virtual events have been broadcast from the house, but going into the future Vorse’s home will be open for visiting artists to stay in the eight bedrooms, and also to host events, exhibitions, and fundraisers, in partnership with the Fine Arts Work Center, the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, Twenty Summers, the Provincetown Film Society, and the Provincetown Theater. Space, and in particular housing, is often the hobgoblin of any new creative idea in Provincetown. The Vorse House, therefore, is a godsend. With limited resources in town and organizations often in competition for the same donor dollars, Fulk hopes the Vorse House releases some of the pressure and creates an atmosphere of cooperation for the town’s arts organizations and nonprofits.

“The big idea is to let anyone use it,” says Fulk. “To let it grow into what it can become. If you have an idea, let us know, and most likely the answer will be ‘yes, let’s try it.’ When I reached out to these organizations in town, they told me, ‘Yes! We have a thousand ideas.’”

The other day Fulk gave a socially distanced tour of the home to John Waters, who gave him the greatest compliment: he said it looks exactly the same. In Provincetown, Fulk leads by example, trying to combat thoughtless development and soulless design. So many homes in Provincetown have been gutted, stripped of not only their exterior, but interior character. When you have a home with original flooring and woodwork, Fulk doesn’t understand why someone would straighten out the staircase or the uneven fireplace mantle. Provincetown is not a fancy place, never will be, says Fulk. That character and charm is the design, says Fulk. And when it comes to the Vorse House, he credits much of the success to working with local contractor Nate McKean, a Provincetown native, who doesn’t just understand the bones of a Provincetown house, but its very marrow. This latest project is a bit full circle for Fulk, as many years ago he bought a copy of Time and the Town when he saw it in the window of the Provincetown Bookshop. In the future, his plan is to either leave the house with an endowment as a private, independent institution or leave it to PAAM. But for now, he’s going to revel in what new voices come out of the old house in town that has him as bewitched as Vorse found herself.

“I was mesmerized immediately,” says Fulk of his first visit to Provincetown. “I really became enamored with not just Provincetown, but its history. I’m still amazed when someone tells me how much they love Provincetown, but have never read Time and the Town. After all these years I still read it over and over. Her voice is so strong, and you can feel it in her house still.”