by Rebecca M. Alvin

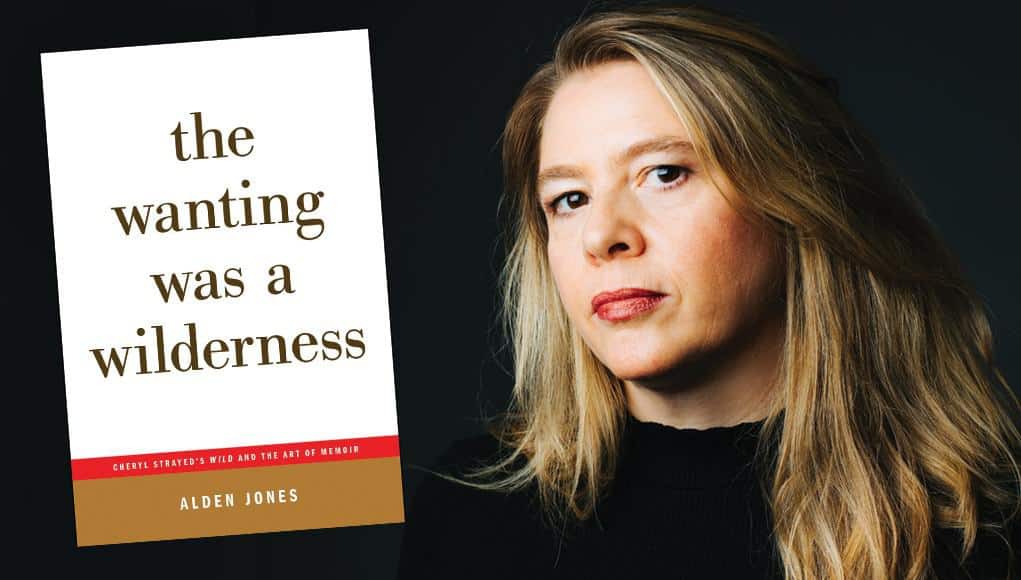

Top Image: Alden Jones. Photo by Adrianne Mathiowetz

When writer Alden Jones was approached by Fiction Advocate, a small book publisher, about writing something for their new series of books about books called Afterwords, Jones felt it was a great fit for her. “ I had just had my third child, so I was very overwhelmed and thinking about writing a big novel, and I realized I just didn’t have the bandwidth for a big project,” she recalls. They gave her a list of books they were interested in and told her to choose something. Although she had not read it herself, Jones selected Cheryl Strayed’s memoir Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail because the author was someone she already admired. (A writing professor at Emerson College in Boston, for close to two decades, Jones says she’s never had a student she didn’t assign Strayed’s essay, “The Love of My Life.” )

As she read Wild, she started thinking about events in her own life back in 1992 when, as a young woman, she participated in Outward Bound, a program for youth and adults that seeks to build strength and resiliency through wilderness excursions that test one’s limits. For Jones, the program was an intense experience that put her in touch with her sexuality, her identity, and both her strengths and weaknesses. It connected strongly with Strayed’s story of a solo 1,100-mile hike in the wilderness, that she’d embarked upon for self-discovery after the death of her mother, a divorce, and the development of a troubling heroin habit.

“Part of the reason I had put off reading [Wild], was that I knew it was going to bring up all these memories of my Outward Bound experience, which was 85 days and very intense and involved a love story and all that. And so this book assignment prompted me to say, ‘okay I’m going to have to deal with it,’” she says. “And the point of the author series is it was to give book critics room to both analyze the text but also meander in whatever way they want… So I thought, ‘okay, well, I’ll figure out how this book will be structured as I write it.’”

Two years into writing what eventually became The Wanting was the Wilderness, Jones’ life took an unexpected turn. “I got about halfway through and I was sort of going back and forth between critical analysis and my own experience, and I was like, ‘they’re going to have to come together somehow,’ but I wasn’t sure how. And then right in the middle of the book, I got divorced,” she says. “I didn’t write for about two years while I was dealing with all the life stuff. And during that two-year period, I was really thinking ‘why am I having this moment of reckoning? I feel like it connects to the book.’ And I was thinking the entire time about how the events of my life were selecting the content of the book.”

The resulting memoir is a 185-page combination of memoir, literary criticism, and how-to book on memoir writing. Written in a natural, flowing style, the reader is likely to read it cover to cover in just a few sittings, coming out with a better understanding of Strayed’s book and of the very nature of memoir as a genre, as well as some deep reflections on the personal growth and discovery we often come to through relationships with others as well as, perhaps more importantly, reliance on ourselves.

“I think if you haven’t figured out yourself as an individual, it’s like you look for those missing pieces in other people that you have relationships with, and that’s a problem. That was one of my problems, is that I was looking to other people to sort of feel complete and that I couldn’t really achieve true autonomy until much later in my life. And that’s why I had to push the story so far into the future beyond Outward Bound. It was really when I first gave birth [to my children], the actual act of giving birth was like, ‘I really can do anything!’ So that was like the final act in self-reliance,” she explains.

Memoir-writing is a distinct form with it’s own very particular pitfalls and considerations. Jones, who has written in a variety of genres, is keenly aware of what makes a good memoir. At the same time, she’s equally clear on the dangers that can turn a writer’s personal story into something that doesn’t resonate with the reader, which is after all the ultimate goal of publishing a book, if not of writing it in the first place.

Sometimes the problem isn’t so much leaving out details as it is over-sharing. Jones points to Madonna’s SEX, an explicit photographic book that came out in 1992 and was almost universally panned because, as Jones puts it, after years of teasing, suddenly Madonna was completely, explicitly layed bare with no illusions and no allusions. In contrast, in the memoir world, Jones cites Mary Carr, author of The Liar’s Club: “Carr is a brilliant example of someone who knows when to withhold. Withholding keeps the reader more interested both on a narrative level but also on a content level.”

Ethically, the memoir is perhaps the hardest type of book to write because you’re working with the truth as you see it—or as you remember seeing it—which inevitably means some of the people who were a part of your real-life story will end up looking bad in the book. But also, people you care about will read the book and it can change the nature of your relationship in a very real, lasting way.

“The line between fiction and memoir can be very thin. I mean there are certainly fictional elements in memoir, and there are always autobiographical elements of a novel,” she explains. In her own book she says she was very careful about how to portray other people fairly and not villainize them in order to elevate herself. “If you’re quoted in the memoir, it’s always [the author’s] story. So their interpretation of events and their interpretation of the characters is their interpretation. It’s not necessarily the objective truth. I addressed it in The Wanting was the Wilderness, that I could have chosen to simply use some really damning quotations to set up my crewmates as villains, like homophobic, horrible people, because that would have been easier to do by just cherry-picking certain things they said. And that would enable me to look like some kind of victim or somehow better than those people, but that wasn’t true. It wasn’t true to only show those situations and to not show my own flaws.”

Jones has had a place in Provincetown since 2001 and was supposed to be in town to promote the book for an event earlier this month, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, that plan was scrapped and the book release has been pushed to the end of August.

In the meantime, asked about tips for writers thinking of working with material for a memoir, Jones offers, “I think it’s a great idea to take notes right away, while you’re still in the material, but it’s almost never a good idea to try to write the entire story while you’re in the middle of the emotional experience. I do think it’s a very good idea to get some distance from it, but it’s always a good idea to take as many notes as you can.”

The Wanting was the Wilderness by Alden Jones (2020, Fiction Advocate) is now available wherever books are sold. Please support your local bookseller.