Gaston Lacombe’s Muse

by Rebecca M. Alvin

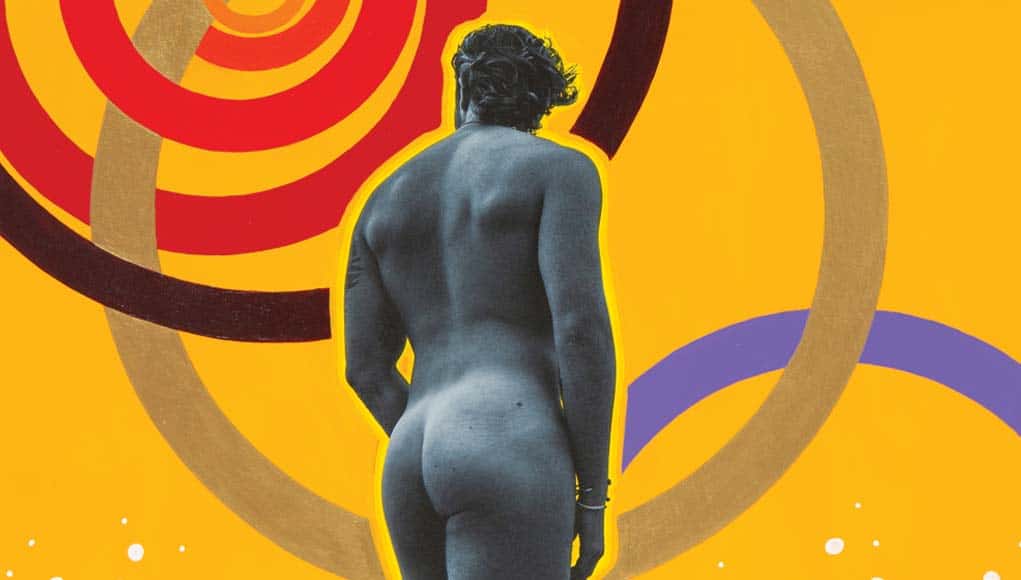

Top Image: Splash (mixed media photographic print, acrylic) (Detail)

When Gaston Lacombe arrived in Provincetown in 2016 he was in the midst of a dramatic transition. After being in a relationship with his husband for 21 years, living in Washington, D.C. as a successful photojournalist, everything came crashing down. The marriage ended and Lacombe’s dissatisfaction with the work he was doing reached an apex. He came to Provincetown at the invitation of a friend who had a house here, just to reflect and regroup. It was supposed to be a temporary refuge, but as is the case with so many who visit these shores, Provincetown wrapped Lacombe in an energy unlike anywhere else he’d been in a life that had already spanned several countries and continents.

“First of all, as an artist, I found a place where artists were seen,” Lacombe explains. “I had a studio in D.C. I was working in D.C. But it was a constant hustle and I constantly felt very much invisible. While here, people come here specifically to see art, to interact with it, to make it, to buy it! And that for me was a big revelation.”

Lacombe also was inspired by the number of artist-owned galleries. He cites as examples James Frederick, Curtis Speer, Adam Peck, and Kyle Ringquist. These artists work and sell their art here in Provincetown in their own spaces, and that provided a model for Lacombe as he set up his own studio/gallery and eventually made Provincetown his home base.

Of course, in addition to the embrace of artists here, Lacombe was struck by the freedom he felt to be himself, as a gay man, in a community like no other, what some (including Lacombe) have called “the gayest place on Earth.”

“Your brain is suddenly free of all stress and free of all hindrance, free of all this internal monologue: ‘Where am I? Who am I talking to? What am I wearing? Can I be here?’ You know, it’s gone. So that felt like, in many ways, the place I needed to be,” he explains.

Lacombe discovered a way to work with photography that was more satisfying and, he says, less prone to the frustrating problem of image theft online, and also considered more valuable. Photojournalism, he says, had become disposable in the digital realm where images are passed all over the place, often without attribution, and the focus is always on what’s next. His work was already shifting, but coming to Provincetown opened new creative avenues to him.

Lacombe’s work combines black and white photographs with acrylic paints on a cotton-based paper. The photographs are most often of male models and the natural landscape out here. Layered with personal references and memories, particularly dealing with shame, limitations, and internalized homophobia, they often evoke a simultaneous desire for what’s out of reach and a celebration of the male figure. Often featuring painted circles—sometimes concentric, sometimes intertwining— and organic, flowing shapes, Lacombe says it harkens back to his childhood in Edmundston, a small town in New Brunswick, Canada, when he recalls doodling and drawing abstract designs rather than figurative drawings.

“From a very young age, I was very artistically inclined. But growing up in a very rural, very agrarian, very Catholic environment that was not something a boy was supposed to do,” he says. It was in a workshop with Provincetown painter Pete Hocking that Lacombe found his way back to this childhood fascination. Lacombe recalls Hocking inviting students to draw what they would draw if they were children just drawing purely for the fun of it.

“When I was a kid, basically all I did was draw abstract circles and lines,” Lacombe says. “It was never my main goal to reproduce reality even at seven years old. I was not always making houses and puppies.” Instead, he made giant, completely abstract drawings, which is something he also painted during the lockdown when he didn’t really have access to models to photograph.

And yet, an important connection came for him during that time through a virtual meeting with a model named Justin, whose image is used to create an entire series of works that are the subject of this month’s exhibition, Muse. Justin lived in Provincetown during the early days of the lockdown. Lacombe and he had online discussions for six months and did meet briefly in person, but it wasn’t until September 2020 that they had their first photo shoot. While Lacombe says he finds unique inspiration in each model he works with, there was something about Justin and about the zeitgeist when they met that was exceptionally powerful.

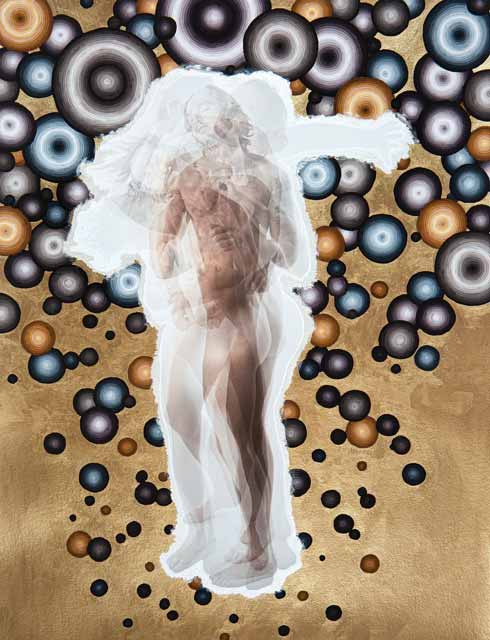

Most of the images center on a photograph of Justin, with the circular design elements painted around him, although there are some that are even more abstracted, with layering of photographs of Justin together to evoke movement, freedom, and release through dance. These works are part of his Dance Oblivion Trilogy, a set of paintings that also stand out for their less vibrant colors and reliance instead upon metallic paints, something very intentional.

“Last summer we were not able to dance. There was this great sense of loss that we felt because all the dance clubs were closed,” Lacombe explains. “When I use metallic colors in my work, it’s very much relating to the ancient religious traditions of using metallics in their work, with gold and silver, and bronze, and copper, because I want to show that this is sacred, this is precious, this is more important than other things… And for me the whole experience of going to a dance club is really a sacred space, especially for gay men. Where you meet, and experience music, and you can completely let go.”

For Lacombe, these images represent the lockdown experience.“That was a very strange time, when social relationships were stunted and just having the most basic contact with someone was dangerous, full of the unknown.” he recalls. “When I look at his photos I really have this strong sense of melancholy almost, like we could have been great friends, we could have, I don’t know, gone out to bars together, but we just had this brief meeting, and it was mostly online, and we were able to create work together, but he’s not here anymore [He moved to New York]. There’s always this sense of ships missing each other in the night, this melancholy, this nostalgia for what never happened.”

Gaston Lacombe’s exhibition Muse is on view at Studio Lacombe, Whalers Wharf, 237 Commercial St., Provincetown, September 3 – 27. There is an opening reception on Friday, September 3, 7 – 9 p.m. For more information call 202.460.6826 or visit studiolacombe.com.