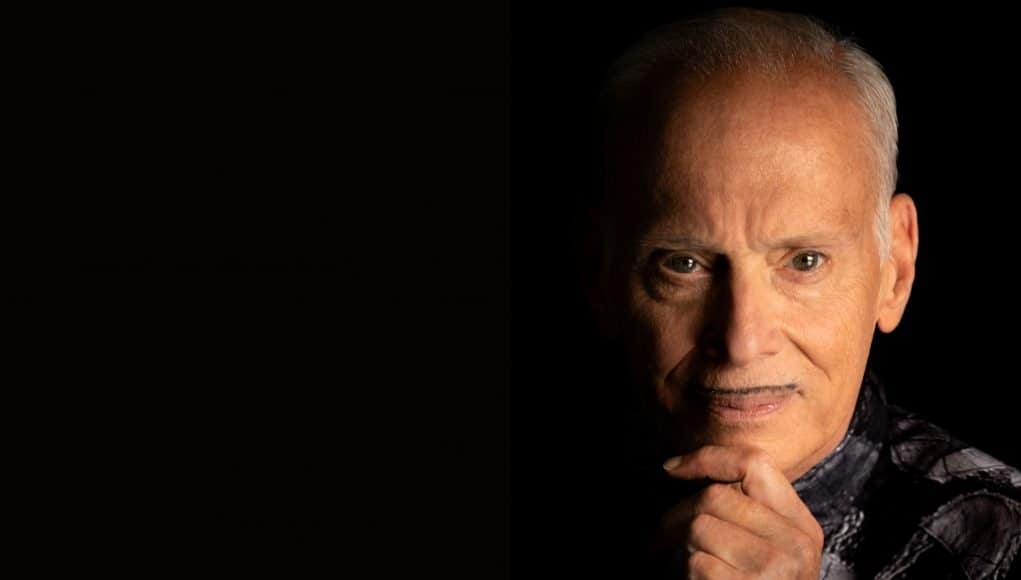

John Waters, Liarmouth, and Pink Flamingos at 50

by G.W. Mercure

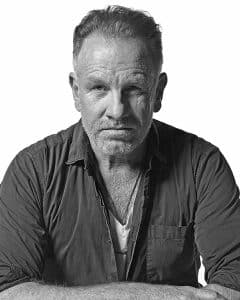

John Waters, the legendary director of Pink Flamingos, Hairspray, Cry-Baby, Pecker, and other films, is busy these days with stories that are new, old, and forthcoming. As a celebrated career marches into a seventh decade of making photographs, films, art, live performances, installations, and memoirs, can a straight line be drawn from the early work to Liarmouth, his debut novel, and beyond?

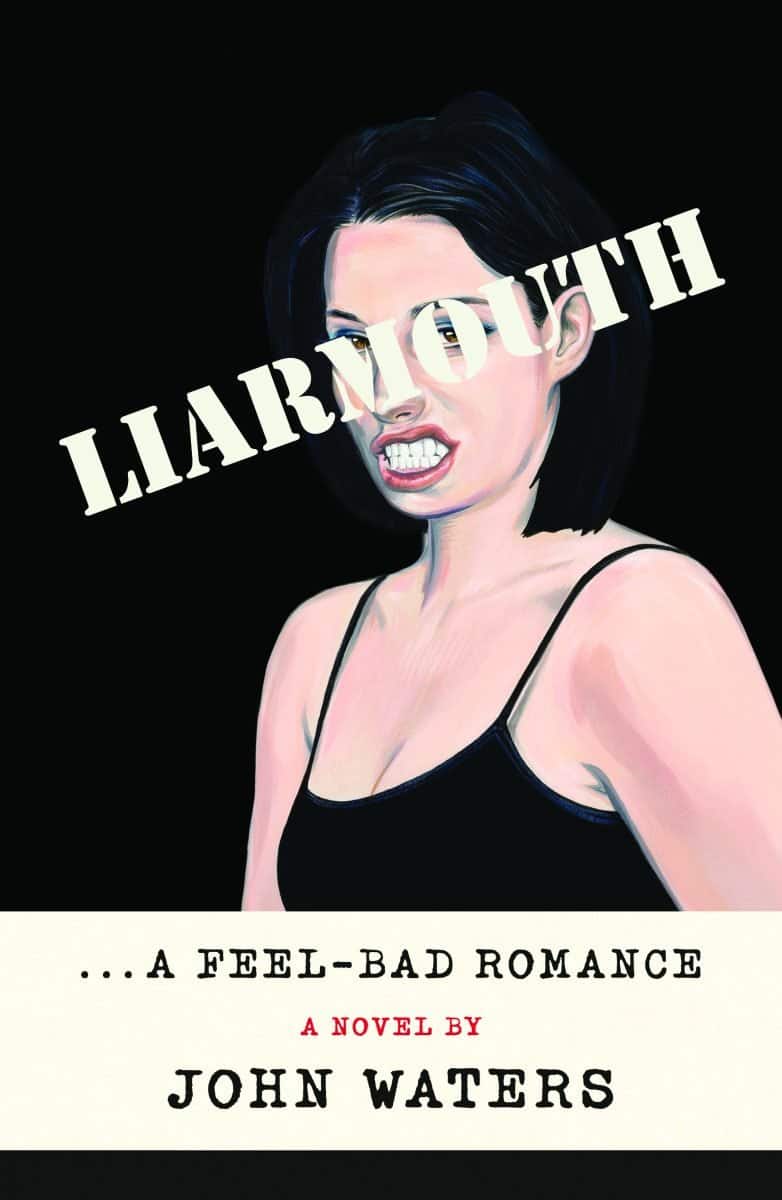

Liarmouth, Waters’ first work of prose fiction, is a reeling and filthy picaresque that might be considered frenetic if it calmed down a little bit. It’s a story that the Pink Flamingos version of Divine might tell. Consider it an amalgam of Apuleius and Nicholson Baker. If you’re still wondering whether it’s very much like the man’s films: there’s an anthropomorphic cock. It tells the story of asexual maverick and airport luggage thief Marsha Sprinkle, who may feel to an initiated reader like a creative descendent of Pink Flamingos’ Connie Marble. Waters thinks the comparison only goes so far. “They would be friends,” he says. “But Marsha Sprinkle would think she is superior.” He also notes “Connie Marble was the villain in Pink Flamingos; in this book, Marsha Sprinkle, oddly enough, is the heroine.”

What the novel and many of Waters’ films do have in common is motherhood. Mother-daughter relationships, in particular, are explored in Liarmouth and Pink Flamingos, as well as Female Trouble, Polyester, Serial Mom, and, to a lesser degree, Cry-Baby and A Dirty Shame. “There’s always drama, it seems like, in mother-daughter relationships,” he says. The drama in Liarmouth plays out in dual attempts at matricide.

In Pink Flamingos, the maternal relationship is not as central. In the film, Harris Glenn Milstead, the drag and cinema icon known as Divine, plays Babs Johnson, who is engaged in a contest with a neighbor to be the filthiest person alive. It’s a big year for Pink Flamingos. The movie will screen during the Provincetown International Film Festival this month for its 50th anniversary. Criterion will release a director-approved Blu-Ray special edition of the film on June 28th. And the Library of Congress has selected it for preservation through the National Film Registry, due to its cultural importance. “It’s hilarious!” says Waters. In the light of political correctness, he observes, “today Pink Flamingos is even worse!”

“I’m very proud,” he acknowledges, but the path of the film certainly didn’t predict such an apotheosis. “I’ve never won an obscenity case. Every time I’m found guilty. Every single time anywhere in the world!” He continues: “When it first came out, it was kind of a comment on ‘what couldn’t you do?’ That’s why we put in eating sh–t. It was the only thing. When you can finally f–ck (in a film), what’s left?” he says of the infamous scatalogical epilogue to Pink Flamingos.

Still, his motivation with the film was purely cinematic. The scenes that confronted the censors were never prurient. “If it was prurient, then they could cut it more,” he says. “Being censored helps you,” he says. “I’ve built a career—in the beginning—of using negative reviews and getting busted and all. Not on purpose, but that’s what I had, and it could work.”

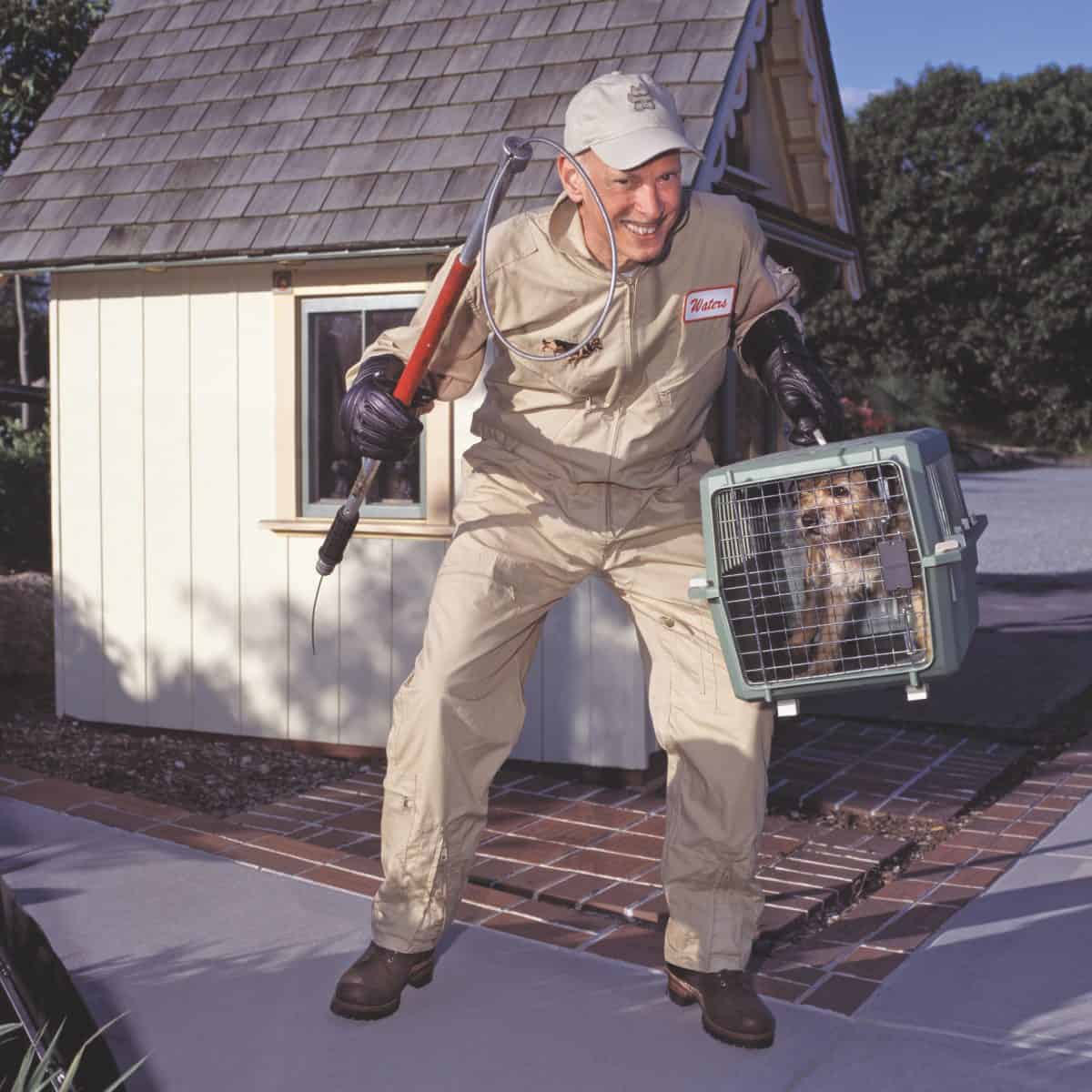

In addition to the landmarks for Pink Flamingos and the publication of the novel, Waters is the subject of a retrospective at the Albert Merola Gallery. The show features work from across Waters’ long career creating visual art. “I think it sort of sums up what I’m about.” The unique assemblies of photographs that are featured function like miniature movies. “It’s like all my work: It’s another way to tell a story…I put them together and write with them—you read ‘em left to right, like a storyboard.” One image featuring Waters dressed in a dog-catcher’s uniform will resonate with Liarmouth readers. The exhibition Probe runs through June 22.

What’s next for John Waters? A lot of things, with at least one commonality: They are certain to draw attention. “I hitchhiked for one book, took LSD for the last one…Turn straight, that would be the last stunt I could do for a book!” He would call the purely hypothetical (I think!) book Come In. “No gay man has ever done that for a book!” Projects that are less hypothetical include another novel, the details of which he is keeping close: “That’s the worst jinx you can have. Never talk about it until it’s done.” He feels the same about a potential film project, which would be his first since 2004’s NC-17 riot A Dirty Shame. “I hope to make another movie again. I’m in the middle of maybe one happening.”

Whether his next project is a film or a book, Waters will likely present characters who are not only devoted to being their true selves, but for whom it is an absolute necessity. And while it’s common to make films and television shows about the marginalized for the amusement of the centralized, with the result of marginalizing them even more, Waters’ films had those margins as their target demographic. The “Trash Trilogy,” of which Pink Flamingos is the centerpiece, was made for the outcasts and the freaks, and so was Liarmouth. “I think it’s for every character,” he says of Liarmouth. “I am interested in all the characters and I try to think like them. I’m always trying to poke fun at or satirize the inside world of movies and art or any world that has rules…But I like the world that I make fun of.”

The initiated, and even the casually initiated, approach a John Waters film wondering what on earth they are going to see. “The people that come to my shows and buy my books and everything, they want that: that’s what they’re buying when they come to me.” That he is able to elicit that expectation across a range of media and a half dozen decades is one of the things that makes him one of our most dynamic voices in filmmaking, art, literature, photography, and culture. To Waters, it is simple to understand. “I have so many different ways to tell my story. That’s all I’m trying to do: tell stories.”

John Waters will be signing copies of Liarmouth at MAP, 188 Commercial St. at 5 p.m. Thursday, June 16 and his 1972 film Pink Flamingos will screen as part of the Provincetown International Film Festival at 9:30 p.m. also on Thursday, June 16. For more information and tickets for festival events visit ptownfilm.org. His show Probe continues at Albert Merola Gallery, 424 Commercial St. through June 22. For more information on Probe call 508.487.4424 or visit albertmerolagallery.com.