by Rebecca M. Alvin

Provincetown circa 1950 was not like the rest of America at the time. With a long history of being simultaneously a rough and tumble New England fishing village and an active arts colony, the bohemian spirit was alive and well alongside working-class Portuguese fishing families creating a unique vibe unlike the buttoned-up, white-bread world of mainstream America. As the abstract expressionist crowd moved in, they brought with them their social scene, and intellectual and artistic sensibilities, and melded with the small fishing community that had always welcomed the different, the outcast, the misfit. Amongst the artistic circles led by Hans Hofmann and Robert Motherwell, many other artists found a place for themselves, sorted through their artistic identities, and either joined the abstract expressionists, railed against them, or quietly followed their own paths, which in many cases ensured they would be forgotten in Provincetown some 70 years later.

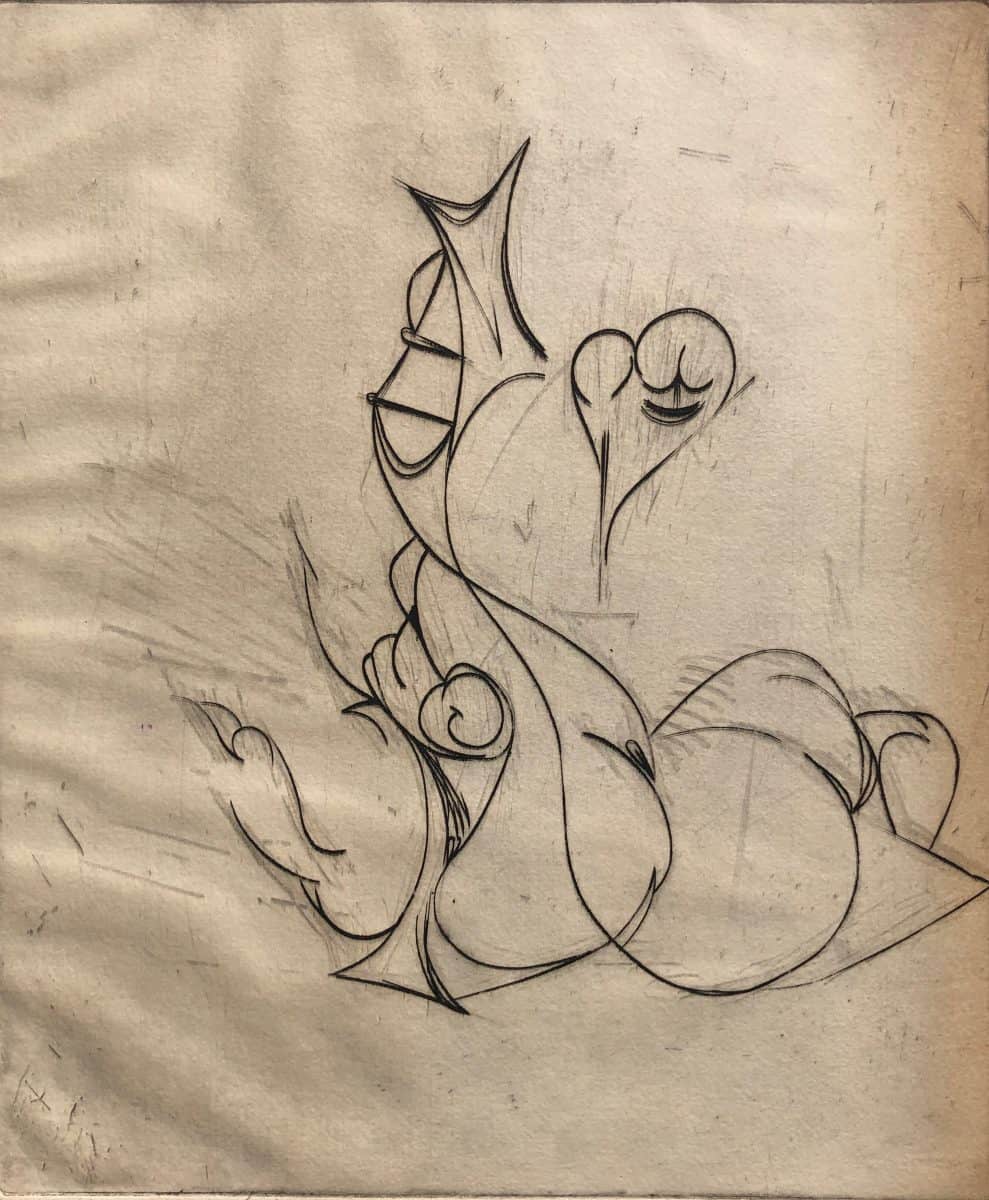

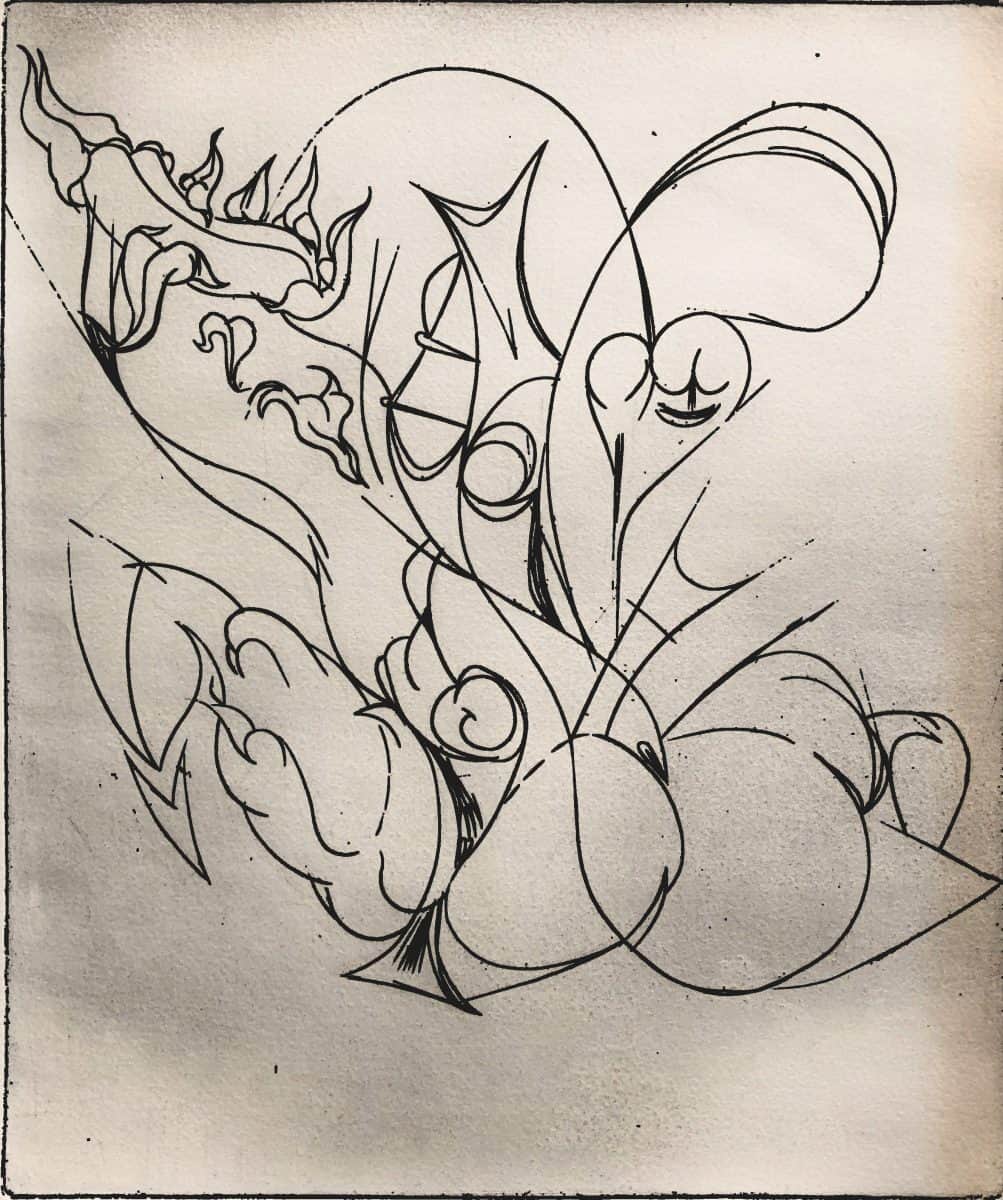

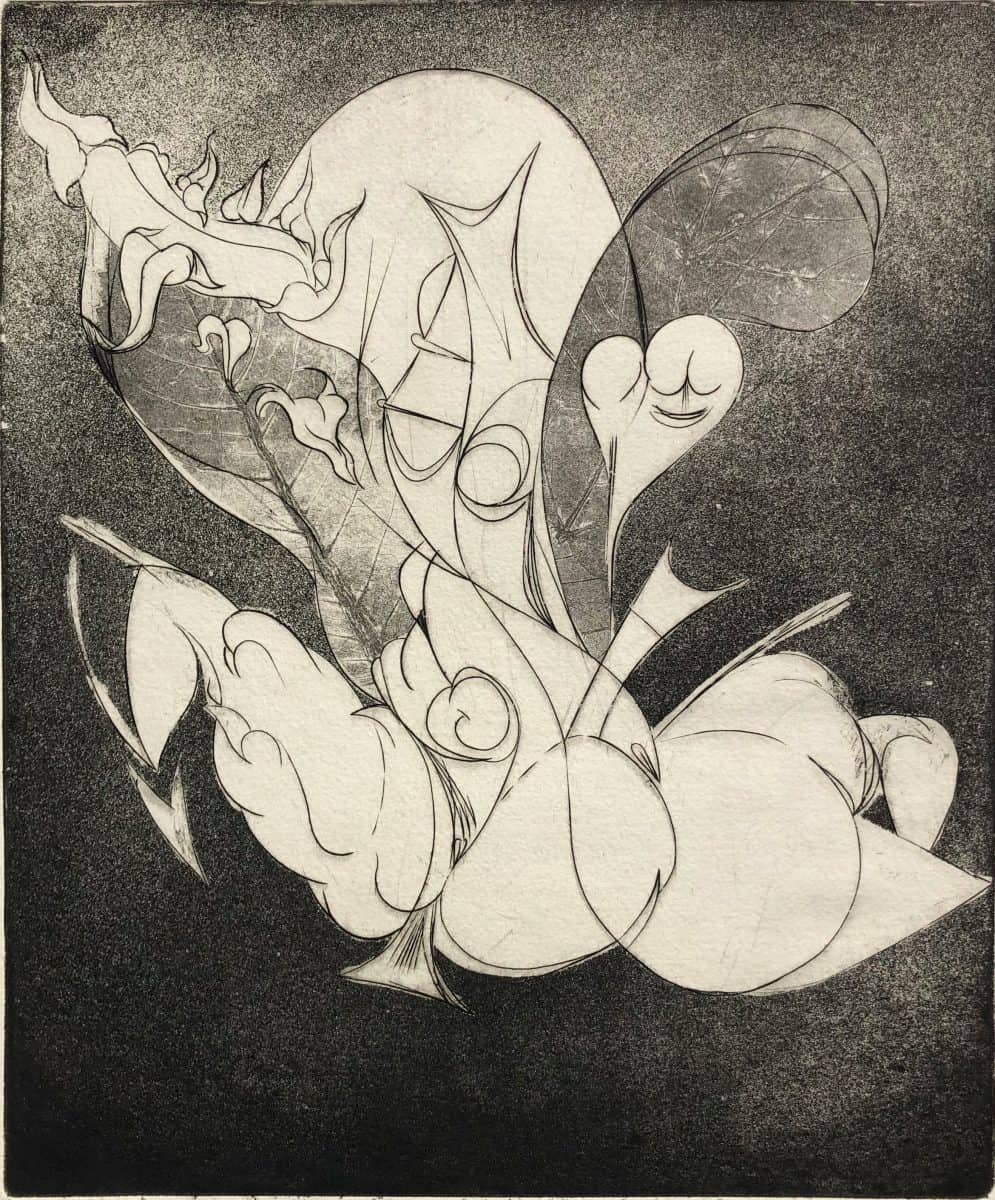

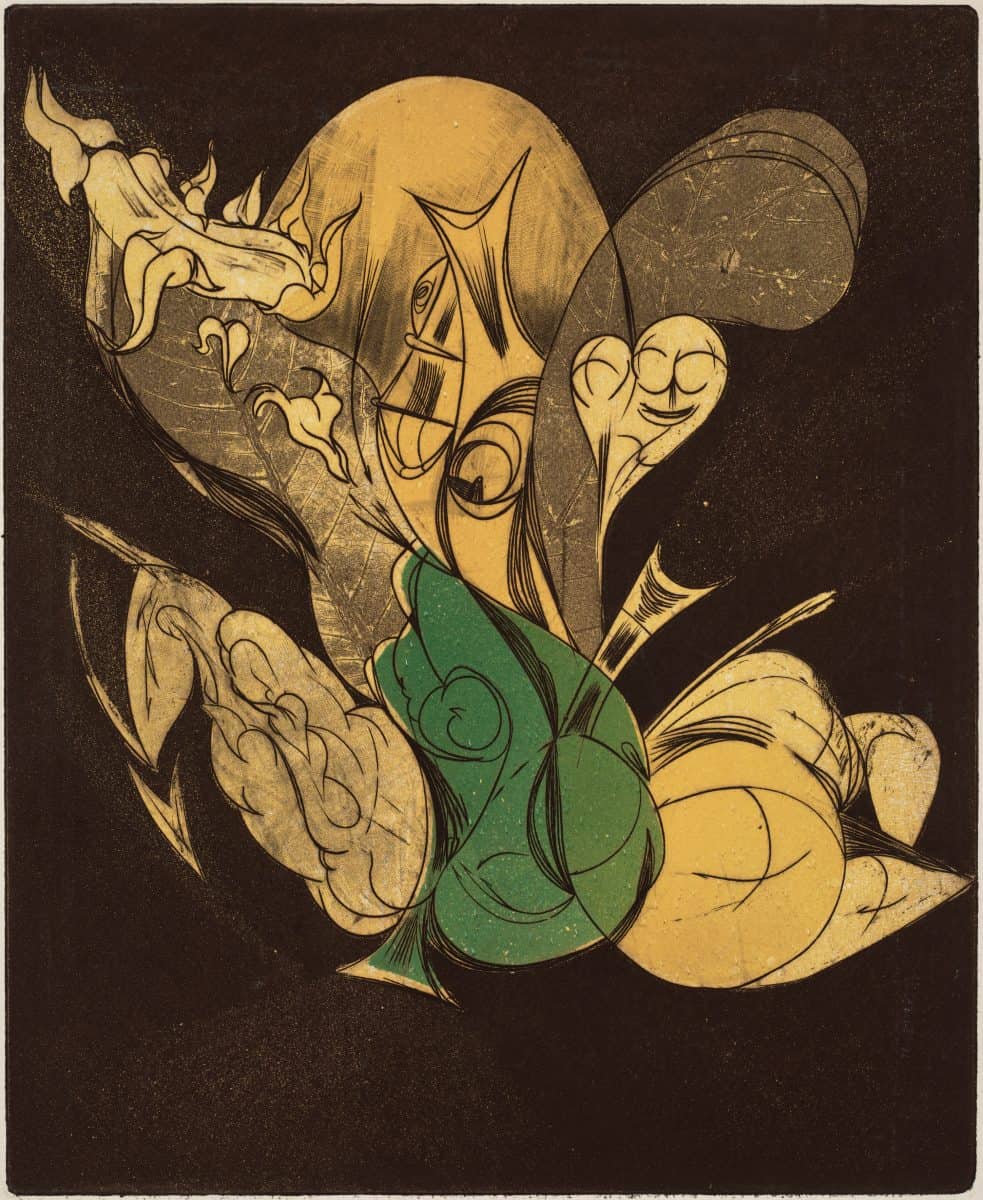

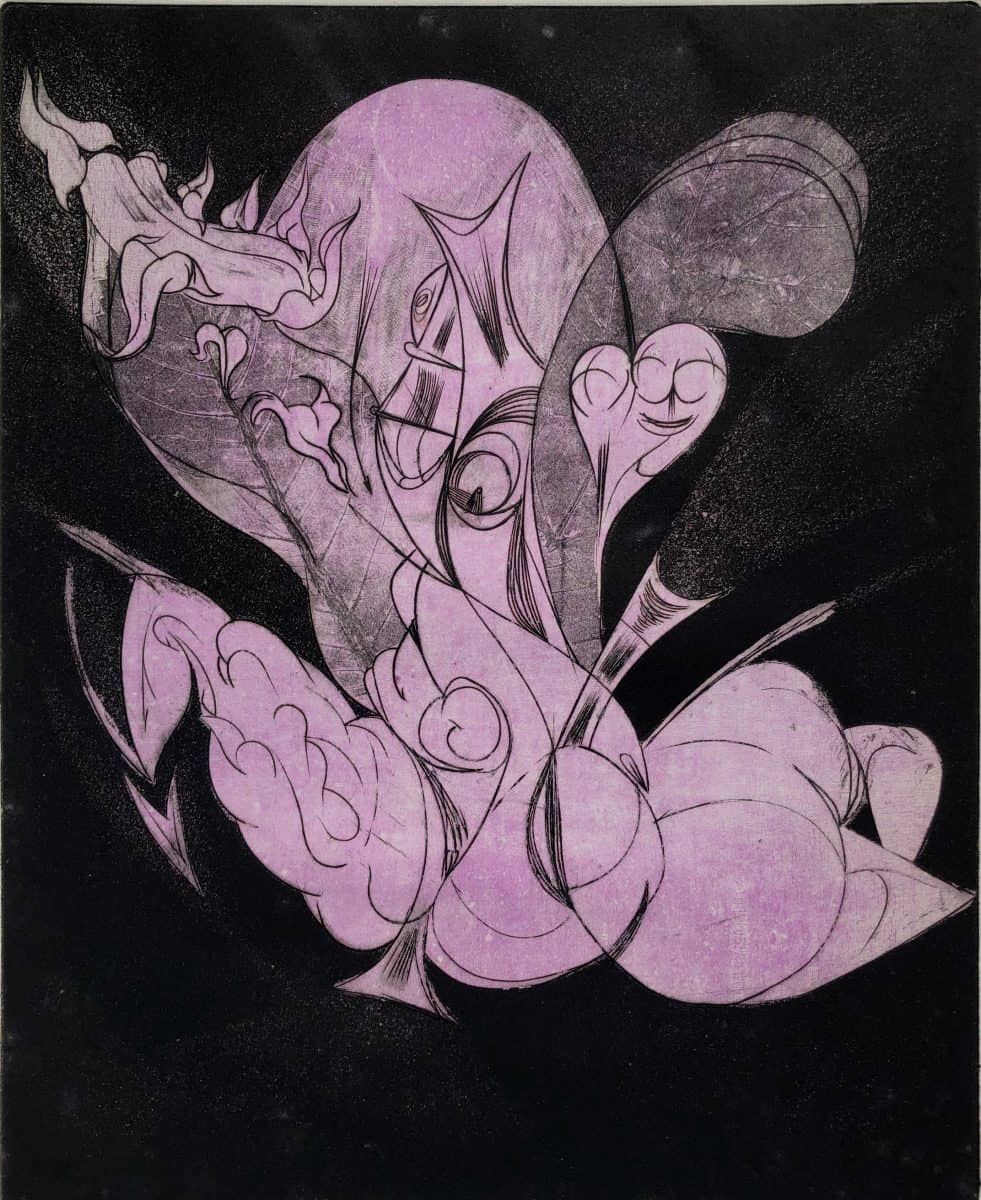

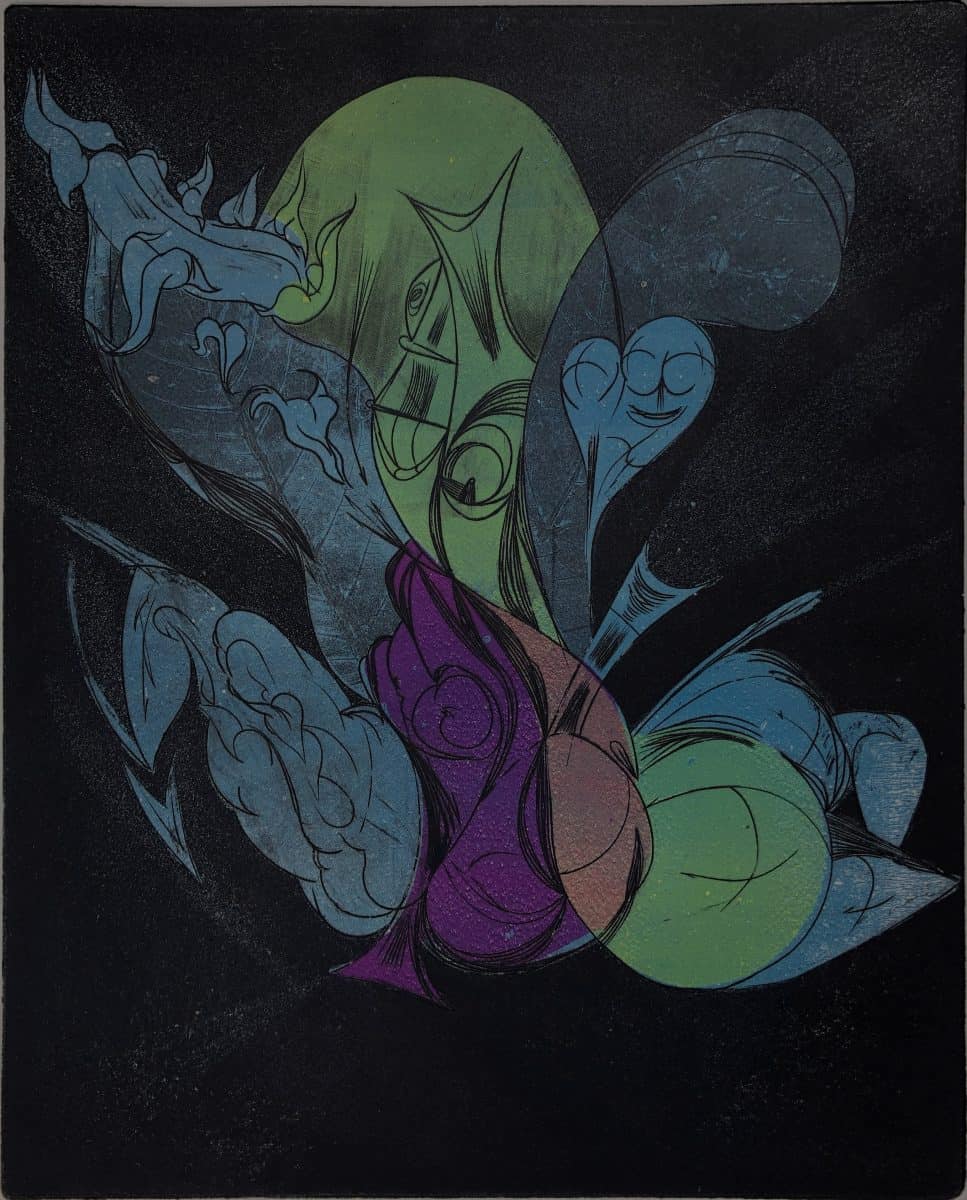

references for Barooshian’s work

The Boston-based Armenian-American artist Martin Barooshian was introduced to Provincetown by his girlfriend at the time, artist Reba Stewart, around 1950, and he continued to spend time here throughout the 1950s, enjoying creative, intellectual, as well as sexual adventures, as did so many of his contemporaries. But Barooshian was never a part of any specific group. Although he held many ideas in common with the abstract expressionist (such as taking inspiration from surrealism), he didn’t subscribe to what Michael Russo, trustee and curator of the Martin Barooshian Art Trust and also a friend of the artist, describes as the “ultra-masculine world of the abstract expressionists.”

Russo explains Barooshian was an outsider in every way. “He wasn’t a part of that. I mean he certainly wasn’t a Beachcomber,” Russo explains, referring to that venerable social club where so many artists made their connections and which, to this day, has always excluded women.

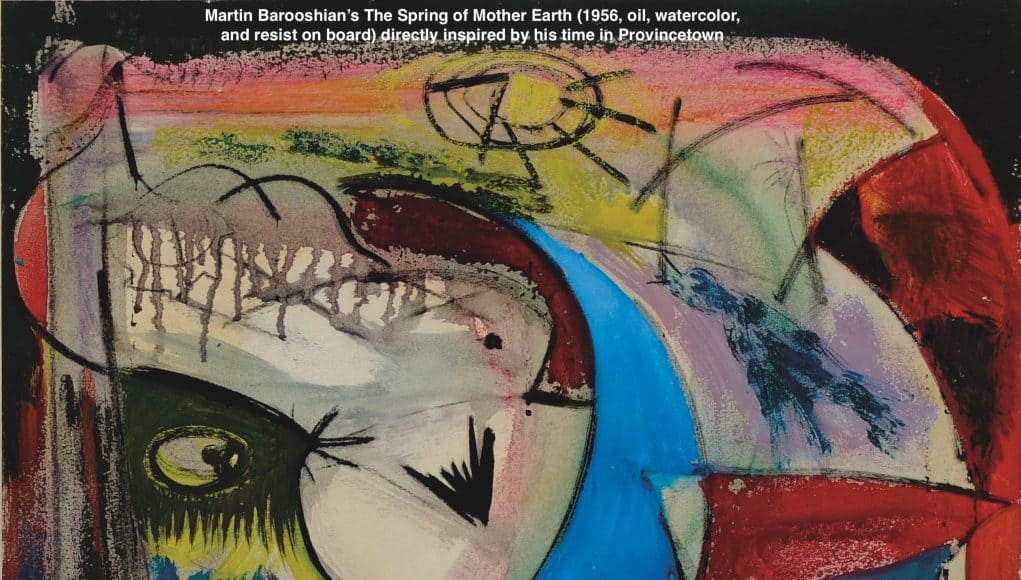

Born in Chelsea, Mass., he grew up the child of Armenian genocide survivors, and while he was not one to put himself out there as “an Armenian artist,” specifically, the legacy of such horror permeates his work, often signified by anxious looking clusters of people, or a man covering his face or chewing his fingernails in the corner of a painting of otherwise fluid, organic, abstract shapes. And the ornate, almost Baroque nature of his works (what Russo calls “maximalist”) can certainly be traced to the Armenian Orthodox Church’s symbolism. Although he traveled in the same artistic circles as Motherwell and Jackson Pollock, Barooshian’s work was more closely aligned with surrealism, a movement that, at that moment in history was considered dead. And so it wasn’t until almost 50 years later that his work was even represented here.

In 2001, Russo lived in Provincetown and worked for the Julie Heller Gallery. He introduced Heller to Barooshian and his work and she offered representation in Provincetown on the basis of the very same surrealist tendencies that had caused others to shun him half a century earlier.

Heller recalls Russo taking her out to Long Island to see work in Barooshian’s studio. “The surreal work was great, because how many opportunities does anyone have to see a nice chunk of surreal artwork?… With Surrealism, he really was very adept and creative and understood, you know, he knew what he was trying to do,” she says.

Intriguing as his paintings are, it is his prints and his deep knowledge of printmaking processes, gleaned from early work at the famed avant-garde Parisian printmaking studio Atelier 17 with its founder Stanley Hayter, as well as decades more of experimentation on his own that garnered him the most recognition. In fact, even from the beginning, shortly after Barooshian’s first visit to Provincetown, at just 22 years old, the Library of Congress purchased a series of his woodcut prints noted for their representation of modern Atomic Age angst with traditional techniques in 1952. And by 1954, his prints were included in a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

and then the final print and two other variations (bottom row).

The sheer multitude of techniques he experimented with, sometimes in a single print, is impressive, and sometimes mystifying even to other, more traditional printmakers, according to Russo. Having worked with Atelier 17 when it re-emerged in Paris after World War II, Barooshian thoroughly absorbed that environment of experimentation, and while many artists working there in the 1930s and 40s had embraced the automatic processes of surrealism (guided by pure, unfiltered thought, akin to stream-of-consciousness writing) that led them toward abstraction, Barooshian’s surrealist tendencies leaned more toward the exploration of dream imagery and psychological states embodied in figurative forms, bringing together aspects of both surrealism and expressionism in his stunning prints.

Specifically, his simultaneous color printing techniques (color viscosity printing) yielded prints that looked almost like woodcuts, created by pushing the limits of the technique and incorporating other methods, including hard ground, soft ground, mezzotint, and aquatint on a single plate. As Russo writes in his 2020 book/catalog of Barooshian’s early printmaking, “For Barooshian, printmaking was a non-linear and experimental process. As a result, most of his prints move through many states, with variations in composition, color, texture, and technique.”

Heller recalls from her discussions with him that he had an “encyclopedic” knowledge of not only printmaking in general, but each type and every aspect of the art form. “A lot of galleries don’t even know the difference between an etching or a lithograph or an aquatint, seriograph… He knew everything… and I would imagine he’d probably tried every process as an artist, which you can’t say that about other printmakers,” she marvels.

Russo’s book is an excellent introduction, but it barely scratches the surface of the prolific artist whose work is hard to describe, sharing qualities with 1960s psychedelic graphic design, the surrealism of Salvador Dalí, Gorky’s abstraction, and the densely symbolic work of Hieronymus Bosch. Earlier this year, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston added 35 of his works to their collection, including woodcuts, etchings, a monotype, and several drawings, and in a press release they declared these acquisitions “a substantial step in his rediscovery.”

Contemporary Provincetown artists who are familiar with Barooshian’s work, such as Joey Mars and Mary Giammarino, are drawn to his work because of the authenticity of his vision and the imaginative worlds he put on his canvases and prints. As Giammarino puts it, “when you look at the scope of all of his stuff, you know, it consistently represents him; his style is so Martin Barooshian, and there’s nobody else like him really.”

In January of this year, Barooshian passed away, but he was working almost until the day of his death at the age of 92, continually reinventing himself, taking inspiration where he found it, and creating work quite different from earlier iterations of his style. “He just continually saw the potential for creating something,” says Giammarino.

For more information about Martin Barooshian, see Martin Barooshian: A Catalogue Raisonné of the Prints 1948 – 1970 by Michael J. Russo, available on Amazon.com. For more information about Martin Barooshian’s work and legacy visit martinbarooshian.org.