by Steve Desroches

There are certain works of art whose creation marks a before and after moment for the genre, a game changer that starts a whole new era. And there are those that, in addition, become classics as the humanity or idea represented in the piece is so aptly communicated it resonates beyond its time and generation. It also takes a bit of kismet where all the stars align and things hit at just the right cultural moment. It’s at once hard to understate the influence the film Midnight Cowboy had on cinema while it’s also easy to take it for granted as its contributions can just be seen as the new normal while dismissing the actual big bang of the new universe it was creating.

on the set of Midnight Cowboy.

Photo: Michael Childers

All images courtesy of Zeitgeist Films

Now, more than 50 years after its release, it’s entirely appropriate to further examine the film’s influence and to do so as part of the Provincetown International Film Festival, an annual celebration of independent film, emerging artists, and those cinematic stories of the marginalized. Many of these contemporary voices and films can draw a direct line back to the 1969 film as is shown in Desperate Souls, Dark City And The Legend Of Midnight Cowboy, a new documentary by Nancy Buirski screening at the festival on Thursday. It is not a film about the making of Midnight Cowboy, but rather an exploration of the artists who made the movie as well as the cultural moment in which it was made and the reality of New York City at the time and what it said about a difficult time in American history.

“I find myself constantly using the word inevitable,” says Buirski. “The sense that you could start to question what authority was feeding you prior to the Sixties made this film inevitable.”

All images courtesy of Zeitgeist Films

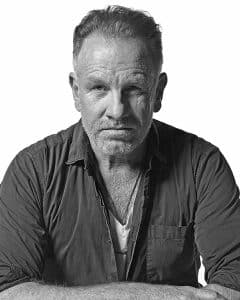

Desperate Souls illustrates the lead up to Midnight Cowboy as almost a cosmic event with infinite celestial bodies all speeding through time and space headed for a cultural collision. The influence of French New Wave and Italian Neorealism capturing the gritty reality of post-World War II Europe and the corresponding trauma, the personal lives of director John Schlesinger, a gay English man in a country where homosexuality was illegal, and screenwriter Waldo Salt, an American who was finding work again after being blacklisted for years during the Red Scare in Hollywood, the Vietnam War, and the cultural and political upheaval all coalesced to not only allow Midnight Cowboy to be made, but for it to become a critical and commercial success that changed everything forever.

Hollywood was in crisis at the time as they kept pumping out saccharine fare like Hello, Dolly!, Doctor Dolittle, and Cleopatra, all of which bombed at the box office and didn’t resonate with Baby Boomers who were dominating the market share. But Hollywood could no longer ignore the success of more realistic films that dealt with contemporary issues rather than escapism, like Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate that were making money. And thus United Artists, a major studio, rolled the dice with Midnight Cowboy, opening the floodgates for filmmakers thereafter, like Martin Scorcese and Brian De Palma, and giving American cinema a whole new look and focus.

All images courtesy of Zeitgeist Films

“Midnight Cowboy lead us into that direction,” says Buirski. There were independent American films before Midnight Cowboy that addressed taboo subjects and showed the darker side of life, says Buirski, but having a major studio back a story about a New York City con man and a Texas hustler with upper-class women as his clients was as shocking as it was revolutionary. On top of that, the film uncovers a lie about American capitalism, the hypocrisy of the ruling class, and the real lives of those society casts aside in a toxic stew of neglect, judgement, and condemnation. It told the truth at a time when lies were the currency of politics, war, and economics. But at its core, Buirski shows that Midnight Cowboy is a love story, albeit an unconventional one, between two down and out characters who have nothing in this world but each other.

All images courtesy of Zeitgeist Films

Having two men expressing affection and need for one another in a culture that was trying to hang onto traditional expressions of masculinity during wartime, shook the status quo, says Buirski. With Dustin Hoffman as the streetwise Ratso and Jon Voight as the pretty boy sex worker Joe Buck, the two present the characters with a startling vulnerability, wrapped up in Buck’s cowboy costumage, which he says the ladies love, but Ratso points out makes him a laughing stock and more appropriate for the boys on 42nd Street. In protest, Buck yells in defense of his western wear, “John Wayne! You wanna tell me he’s a fag?”

Even questioning John Wayne’s sexuality, the harbinger of what it means to be an American male, was a thunderbolt. And it was a beautiful cultural collision when in April of 1970 Midnight Cowboy won Best Picture at the Academy Awards while John Wayne nabbed an Oscar for Best Actor in True Grit. It was of course an even bigger moment as Midnight Cowboy was the first, and only, X-rated film to win an Oscar, a rating the producers asked for after psychiatrists reviewed the film and called it “too gay-friendly” and said it might invite those struggling with their sexuality to decide homosexuality was acceptable.

While the two main characters are not gay nor in a sexual relationship, Midnight Cowboy is often considered a gay movie not for its actual narrative, but its influence. “The film is not a film about homosexuality,” says Buirski. “It did show how terribly gays were treated at the time. I often say that the film was a Trojan horse for gay issues. It made it possible to make films about gay issues soon after.”

Desperate Souls, Dark City And The Legend Of Midnight Cowboy screens as part of the Provincetown International Film Festival on Thursday, June 15 at 10:30 a.m. at the Art House, 214 Commercial St. Tickets ($20) are available online at provincetownfilm.org. For more information call 508.487.FILM.