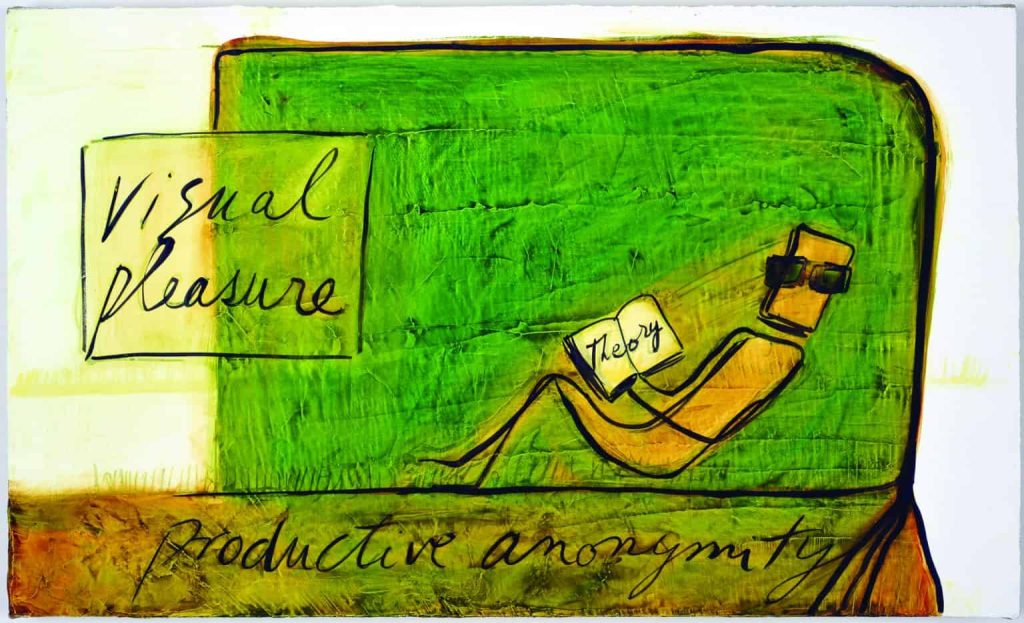

Visual Pleasure/Productive Anonymity, 2013 (ink and oil on gesso on linen, 18×30”)

by Lee Roscoe

Mira Schor grew up on the upper west side of Manhattan, the daughter of Polish Jewish artists (goldsmiths and sculptors) who fled the Holocaust from France to America just as Pearl Harbor brought us into war. She says art came naturally to her as she was surrounded by culture, by artists, and by their work, during the exciting time of the modernist movements of the 1950s. Two were important painters with ties to Provincetown: Chaim Gross, whose sculpture Tourists, is a landmark in front of the Provincetown Public Library, and Jack Tworkov, whose writings she edited in The Extreme of the Middle, published by Yale University Press, in 2009.

She started to draw and sculpt, young, and is now doing a series of works that translate small clay figurines and drawings she made at age 10 to paintings she is making now in her early seventies. (“It’s a conversation between the woman and the child,” she explains.) Coming in summer to her mother’s Provincetown house at age 20, she abandoned her university training as an art historian for a time, to paint and draw. She has done so every summer and finds the two months here some of the most productive. She calls Provincetown creations, her “summer art,” and her New York City work, her “winter art.”

“When I come here, I can focus on what is most alive, what matters to me most at the moment,” she explains.

Schor, who is well represented in Manhattan at Lyles & King gallery, will have her first solo show at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM), which explores her evolution as an artist through time, from the 1970s to now.

She says that her art is about herself and the changes in how she reacts to the world through time, so there is quite a large variety in subjects and styles. “The work has a complex history,” she says. Each phase differs, but the work always represents “who I am right at this moment,” she adds.

What ties them all together is “landscape, language and the figural,” and, she adds, “I’m very political. Sometimes overtly.” She talks of being influenced by feminism, by Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and by her own sister, Naomi Schor, one of feminism’s most renowned scholars. “People see them as objects, but I am interested in women’s intellects, what women contribute to history and philosophy,” she says.

Her paintings visualize abstractly figural females as “beings filled with language.” Originally writings, which she infused into her art, were “illegible, personal, emotional,” but over time the words became readable, political. She gives as an example War Frieze, “perhaps my most important work. The Gulf War lasted three weeks but gave me endless subject matter,” she recalls.

“When I’m asked to define myself, I’ve said, ‘I’m a painter for whom sculpture is at the core. Or, ‘I’m a conceptual artist [but one who] sticks with painting,” Schor says.

Her art is intellectual; she tries to convey ideas through images on canvas and paper. Ever experimental, she says she uses “every means at my disposal for whatever the metaphor conveys.” She began her career using paper, especially rice paper, for both its sculptural quality and its fragility; painting with gouache. She created self-portraits well before she found resonance with those who came before her: Frida Kahlo and Florine Stettheimer. And in the 1980s she was inspired by many new ideas in changing politics, in “the arts world; the language of art itself,” she says, interjecting “I’ve lived through many art worlds.” She was writing about art and reeducating herself and she went back to her academic roots, creating M/E/A/N/I/N/G magazine with Susan Bee as an art forum for artists. She changed her media to oil on linen and canvas. She calls them “oil assisted drawings,” because she says she loves drawing, and it is always a very important factor in the work. (Indeed, PAAM will have a special vitrine for her sketchbooks.)

For her oils, the underlayer is a drawing, and then she layers oils into a thin glaze on top, a translucent varnish—although sometimes she uses a thick palette and carves down to the drawing underneath. Blind Eye is a perfect example of her technique, complexity, and messaging. “It began with ink on a fresco-like surface of gesso,” she says. Then she scraped down to the drawing. It contains a powerful image of an owl upside-down and wrapped in what could be strands of orange-red blood. Beside the owl is an enigmatic shadowy female figure, possibly bleeding. Schor painted it when Trump became president and her paintings, she says, then “became a lot of black with orange and red. I use owls a lot because the owl is a symbol of wisdom,” she says. “Women are under attack; in some of my paintings women are attacked; in some they fight back.” She continues, “I have a sign in my studio (depicted in one of the PAAM paintings) which defines me and my work: ‘Create and Resist.’”

“It’s all related, the way I write, the way I draw. My art loops back on itself.” Landscape can inform figural aspects, creating a human shape out of a redwood tree or flats of beach—and figures can have their own context or can inform landscape. The work creates a language of dreams and nightmares; the work asks you to question.

The common thread of the PAAM exhibition is the art she created in Provincetown. How it is hung is the last creative act, she says, to show the painting’s unified story, for they should lead one into the other. Though her styles have evolved over time, she feels that there are connections within the paintings to prior phases, and that the pieces themselves interconnect. And Schor is curious to see how the viewer perceives the exhibition as a “complex body of work, challenging as a whole to an audience new to it.”

The exhibition Mira Schor: The Summer Studio is on view now through September 17 at PAAM, 460 Commercial St., Provincetown. Mira Schor will also be in conversation with exhibition curator Breon Dunigan, in a Fredi Schiff Levin lecture on Thursday, August 10, 6 p.m. For more information call 508.487.1750 or visit paam.org.