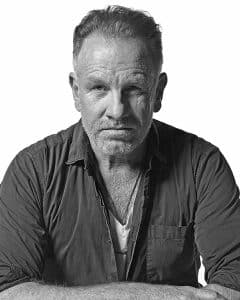

Artist Salvatore Del Deo in his studio. All images courtesy of Tatiana Del Deo

by Lee Roscoe

Whether painting the Outer Cape landscape, architectural details, flowers, portraits, clammers and fishermen, artists’ mannequins mixed in with real people, ballet dancers, saints, boat wrecks—whether on huge canvases or smaller– Salvatore Del Deo’s art feels massive, immediate, and intense, pulsing with themes of love, work, the joy in life, celebration of the common man and the common humanity in all of us. Original in composition and color, you know it’s a Del Deo when you see it.

He’s been a carpenter, fisherman, restaurateur, house cleaner to put bread on the table, and always an artist, a painter in oils, a Provincetown legend and an American Master. The Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM) is currently featuring his work through November 26. Del Deo says it’s all director Christine McCarthy’s choices. “She spent days in the studio. I don’t know where anything is now,” he laughs. Speaking a week before the show opened, Del Deo says whatever will be at PAAM will undoubtedly express the honesty and truth he strives for in his work.

(oil on canvas, 1998, 35 x 52”)

Cleaning up from the day’s painting in his half-dim, half-daylit studio filled with work in progress, he says about how he came to art, “I was born with it,” drawing portraits of his parents on shopping bags when he was seven years old.

When asked where he grew up, he responds, “It depends what you call growing up. I came alive when I came to Provincetown in 1946 at 17 to study painting.” He studied with Henry Hensche at Charles Hawthorne’s school, which, with Hans Hoffman’s school, centered the Provincetown art colony in the American art world at large. He also studied with Edwin Dickinson, and says he owes much to John McPherson, with his mixed Scottish brogue and southern accent, who“used to teach about form and the way the form built up the figure,” by having students look at sculpture. “Rather than anatomical it was more volumetric so to speak,” Del Deo explains.

Before Provincetown he lived outside Providence, Rhode Island, and could “drive for 50 miles and only see Italians.”

Del Deo has used a dune shack in the Cape Cod National Seashore’s Peaked Hill Bars National Historic District as a family getaway and alternate studio for over seven decades. (He does have a studio and home in Provincetown proper.) Del Deo says that he was given the shack by “Frenchie” Schnell (often spelled as Chanel), and that he has paid taxes on it and made improvements to it over decades. But, recently the National Park Service mandated that the Cape Cod National Seashore turn his and seven other dune shacks over to open bids for new renters, threatening to evict Del Deo and other longtime shack dwellers. (Not the first time eviction has been a possibility, in the 1980s a bid by the park to take over the shacks by eminent domain was defeated, and the buildings were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2012.) The shack dwellers, some of whom claim to have leases (and who have maintained and improved their abodes), want the first chance to keep leasing their habitations, and object strongly to evictions.

Del Deo says he is “ashamed of his country, that they would use taxpayers’ money to fund a study [by anthropologist Robert J. Wolfe, and then] throw out” his findings, which were, according to the Boston Globe, that the shack colony qualified as protectors of “Traditional Cultural Property.”

Bill Burke, park historian for the Cape Cod National Seashore, explains the National Park Service owns 18 of 19 dune shacks, and that as far as Del Deo’s abode is concerned, the Schnell family held a life lease in the name of a family member who died, thus opening up a competitive bid for a new lessee. [Ed. Note: After press time, Del Deo did decide to accept the lease.]

Regarding this bruhaha, Del Deo jests that rather than his art, this may be his legacy since the news of it has gone global. He speaks of the irony: if not for his late wife, writer and activist Josephine Del Deo’s 40 years of diligent advocacy, the Seashore itself might never have been created. The park has just offered him a five-year lease, but he says if the other lessees facing eviction are not included, he will turn it down.

He says he has been lucky, as a painter (commenting that “painters are privileged people” in being able to bring “notice” of the world to their canvases), and as a husband to his late wife Josephine. Married in 1953 for 64 years, it’s an epic love affair. “I had so many doubts. My wife always encouraged me. I would look at something and say this is horrible and she would say no, ‘you’re going to grow, you’re going to be a good painter.’” He adds, “I listened to my elders,” for when first in Provincetown he met Harry Kemp, the famed poet of the dunes told Sal about “this young lady in town who is a poet who will be your mate for life.” He pauses, saying, “And I helped her. I didn’t go to college. I don’t know grammar, but I know when something is good to read.”

At 95, he comes to the studio to paint every day. Del Deo brings his aliveness to his painting, and painting, it seems, gives him life. He never has anything concrete in mind when he begins. He may work on something old or start anew. “It’s always exciting to start a new canvas; it’s enticing to get into that white space—awesome but also frightening; sometimes I will put a tone on canvas to break the shock.”

Enamored of the joy of the process, he is unhappy often with the results. “A painter friend told me when you paint a picture and you think it’s so great, put your foot through it. I haven’t put my foot through it, but I’ m never happy with what I do.”

(oil on canvas, 1976, 48 x 72”)

He mentions how Provincetown itself both inspires and sometimes traps young painters by the view itself, that the architecture takes over. He does paint the town. “But it doesn’t satisfy me. I had to come to the inner core of this crazy land, there’s an anatomy here to this landscape of long horizontals, unlike other places.”

His eyes shine with the light of a man a third of his age, a young heart in an old soul well aware of his artistic antecedents. “My grandfather is Cezanne; he’ s the guy to go to,” he says, explaining he broke new ground discovering the “inner architecture of a landscape,” which it takes a long time to see. Yet he doesn’t like to be pinned to a style of painting. As he says, “Style is the death of art.” He is also inspired by Diego Rivera (he climbed a ladder in Mexico years back just to talk to him), and he pays homage to Manet and Degas.

He says, “Hensche and Hofmann came from the same tree. Titian is the father; he’s the tree and all these branches come off of it.” He explains that while the Florentines are known for draftsmanship and are more cerebral, the Venetian Titian “deviated from them because he wanted to attack the canvas immediately. And that is what connects with the abstract expressionists, as opposed to traditional painters, and makes the Provincetown school so unique—the dictum that the action in the painting is the painting; if you have something to say, that’s when you say it. So, I have just carried that on.”

Salvatore Del Deo: 75 Years in Provincetown is on view through November 26 at PAAM, 460 Commercial St., Provincetown. There will be an opening reception on Friday, October 6, 6 p.m. and before that, a Fredi Schiff Levin Lecture with Del Deo and his son Romolo on Thursday, October 5, 5 p.m. For more information call 508.487.1750 or visit paam.org.