Billy Forlenza Courtesy of Lynn Stanley

by Lynn Stanley

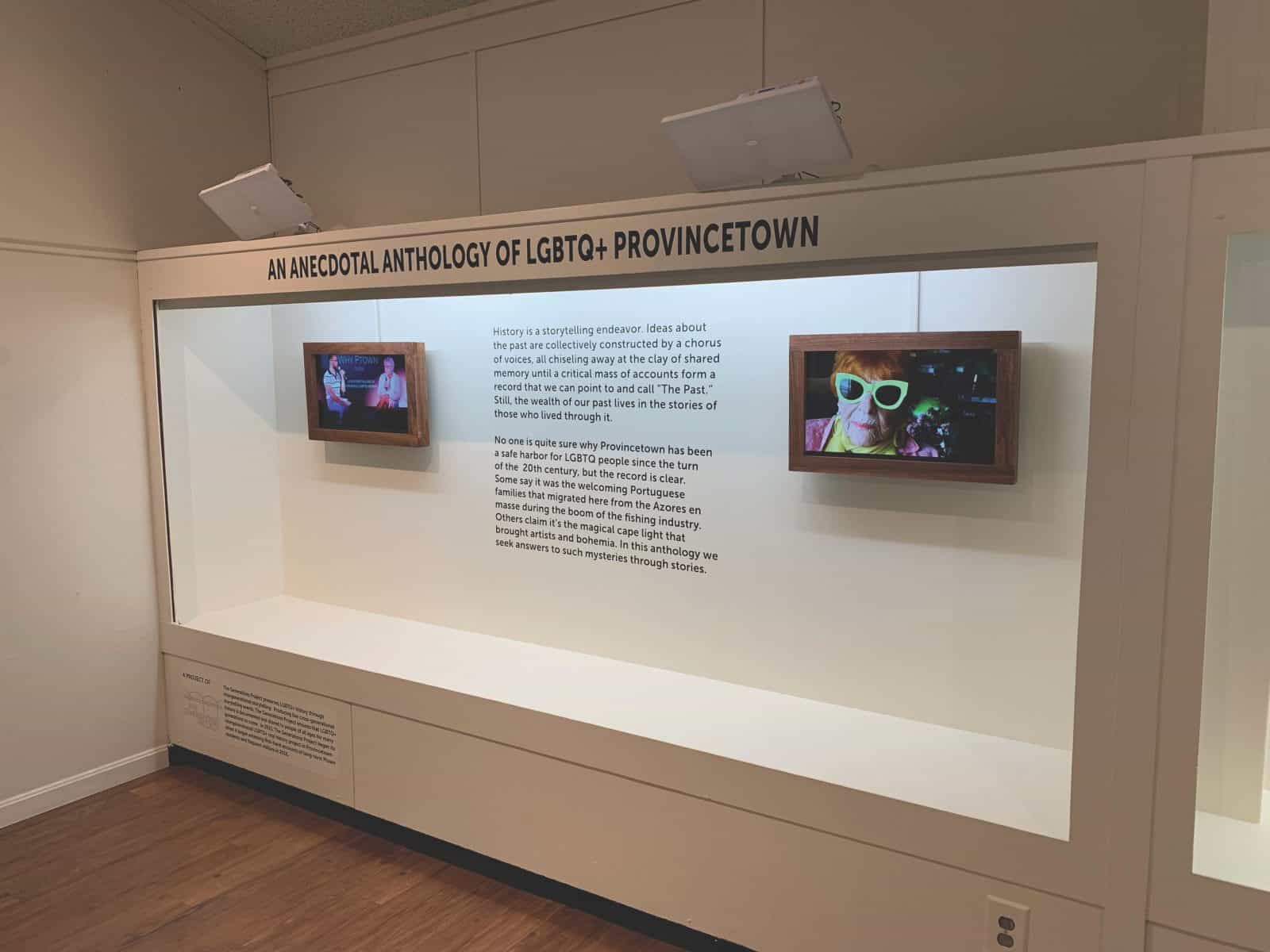

In a quiet corner of the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum (PMPM)—sandwiched between cases filled with centuries of the fishing village’s physical culture, and an exhibit that explores the relationship between the indigenous Wampanoag and the Mayflower pilgrims—you’ll find a series of monitors playing video interviews on a continuous loop, along with photographs, keepsakes, and newspaper clippings. This exhibition, described as an anecdotal history of LGBTQ+ Provincetown, was created in partnership with The Generations Project, and is part of that organization’s ambitious mission to reclaim and celebrate LGBTQ+ history through first-person narratives, archival materials, and personal mementos.

On a recent visit to PMPM I stood and listened to each story, and felt the floor shift a bit beneath me. These were the voices of people I’ve known for over 30 years. In a section called “Remnants,” the brilliant Jen Cabral recounts the story of her parents and the A-House. A display devoted to the fabulous Hat Sisters includes an interview with Tim O’Connor, who I met through his support of the youth programs at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM). There were artist interviews, too, including Marian Roth, Ilona Royce-Smithkin, and Jay Critchley, all describing the town’s impact on their work. I found myself thinking back to my first year in Provincetown and missing Billy.

I’d quit my job in New York City and my friend Susan had helped me move to an apartment in a captain’s house built in the1800s. From its windows I could see the lot beside the Ice House, and beyond that, the sea. I thought I was going to stay six months, tops. It was October, 1990, and Provincetown was “rolling up the sidewalks,” as my father used to say. I knew no one. I would be starting from scratch here. As I watched Susan drive away, a red-tailed hawk crashed into the boxwood hedge inches from where I stood. It caught a house sparrow in its talons and pitched skyward. Whatever happened here, it would not be ordinary.

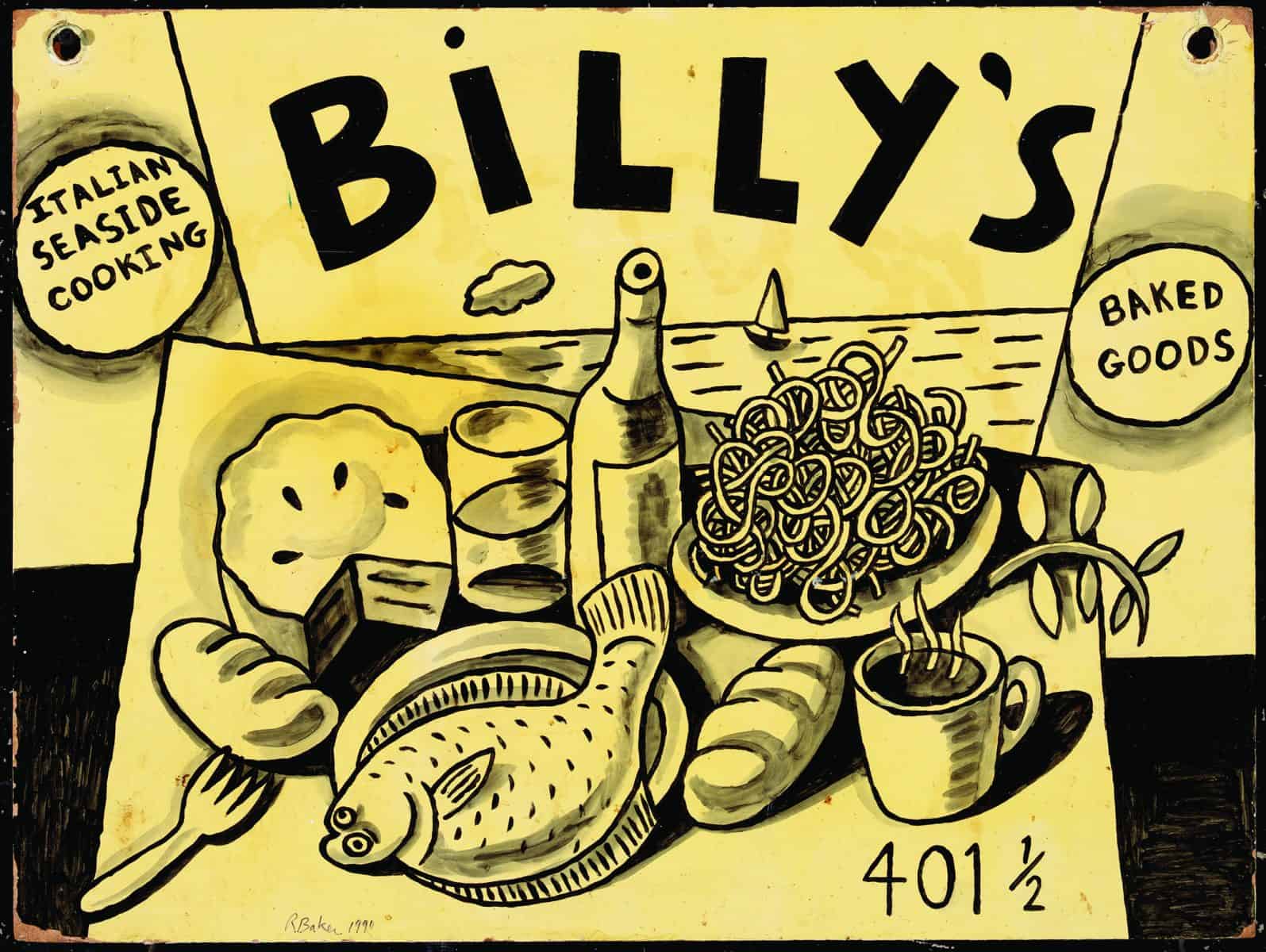

I went in search of food and found a tiny restaurant on the bay side, a few blocks away. The only other human inside stepped from behind the counter to take my order: spaghetti with meatballs. Then he disappeared, and I heard some crashing and swearing down below. He came back breathless, having just encountered a skunk family while throwing out the trash. I didn’t know Billy’s name, or that this place was his. He was just the guy in the kitchen who was also the waiter and the clean-up crew.

Billy lived on Pearl Street, not far from the Fine Arts Work Center (FAWC). I went to every event at FAWC that first winter, and at PAAM too, desperate for art and some semblance of community. Mark Doty lived on Pearl Street then, with Wally. Marie Howe came to FAWC to read. I’d show up at Billy’s and he’d say “Hey Doll,” and offer me some homemade soup. In the summer he grew basil on his back porch, like an Italian grandma. When Hurricane Bob hit, I and another friend crammed into Billy’s bed—trying to sleep as we prayed through the howling wind. I stayed at his house for days, waiting for the power to come back. The air smelled of broken, green wood and crushed leaves.

I came to Provincetown because I wanted to write poetry; I wanted to make art and I wanted to learn. I knew intuitively that I could do that here. Thanks to people I met, like Sally Randolph, Melanie Braverman, Mark, and Marie, I did write, and found my way to the Ada Comstock Scholars Program at Smith College, and then to the University of Michigan and an MFA. I worked odd jobs and survived, as one did back then. I left and I studied, and came back to town, eventually helping kids and teens and adults find their way through art too. All along there were people who helped me become the person I am.

If you look upBilly Forlenza in the Provincetown Artist Registry, you’ll find this: “[He] was a magnificent creative presence in Provincetown from the moment he arrived in the 70’s. He was beloved as a bright spirit, generous and energetic in his support of other’s creative efforts.” Billy was also a teacher. Before moving to Provincetown, he’d taught kindergarten in New Jersey, and classes called Creative Art and Movement. He later received a grant from the Massachusetts Arts Council to teach in the Cape public schools. Without my even knowing it, he lit the way.

Some say Provincetown is a spiritual vortex that pulls in those in need of a safe harbor. It’s hard to describe what the town was like then, or how Billy’s spirit was also a kind of magnet for beauty. It was all magical in a way that you can take for granted, because you don’t yet know what it’s like to lose it. The writer Fran Lebowitz talks about the New York of her youth in a similar, if less sentimental, way. Something like, We were young, and young is better.

This is why The Generations Project is so vitally important. When you hear a recollection, it feels a bit like looking at the night sky after the clouds part: a glittering—something holy and rare—that was obscured. Adam Golub, creative director of the Generations Project, envisions a growing collection of first-hand accounts, along with an interactive walking tour of the town, where visitors and locals can anchor the rich history of the LGBTQ+ community to the streets, buildings, and the natural land and seascapes that make this place so special. In this way, what might have been lost is saved, one story at a time.

In the winter of ’95, during my first semester at Smith, Billy died of AIDS. He always seemed so grown up to me—but he was only 43. I came back from school and we gathered and stood in the cold expanse of the moors, and threw his ashes into the wind. Since then, I have moved 12 times, and everywhere I go I hang Billy’s picture. He’s still grinning, standing in front of the house on Pearl Street. I carry him in my heart.

The Generations Project exhibition, An Anecdotal LGBTQ+ History of the Last Century of Provincetown, is on view at the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum as part of their permanent collection, 1 High Pole Hill Rd. The Museum is open through November 11, when the annual lighting of the Pilgrim Monument will occur at 6 p.m. For detailed schedule, information, and tickets to the museum, call 508.487.1310 or visit pilgrim-monument.org. For information on The Generations Project, visit thegenerationsproject.org.