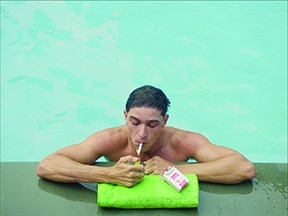

Isaac Powell in D’Oyen’s short film Lollygag

by Rebecca M. Alvin

The gift of uninterrupted time to work on a film project is something profoundly cherished by the few who are awarded fully funded residencies. The Provincetown Film Society offers such gifts through residency programs, including one in April for established queer-identifying filmmakers. This week, the two filmmakers who received residencies that included a week-long stay at the Mary Heaton Vorse House in Provincetown to work on whatever they want to work on, will each screen one of their completed short films for the community at a free screening on Friday, April 12 at Waters Edge Cinema.

The filmmakers, Brydie O’Connor and Tij D’Oyen each use the medium of film to express queer perspectives that range from O’Connor’s intimate portrait of legendary filmmaker Barbara Hammer’s widow Florrie Burke in Love, Barbara, to D’Oyen’s darkly comic exploration of a voyeuristic relationship in Lollygag.

They share a lot, even as their work is strikingly different. Tij D’Oyen started making films as a kid, but instead of moving in that direction after high school. he focused his attention on acting and attended the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, where he received his MFA in 2017. While in school there, he says deviating from one’s major was discouraged. So, it wasn’t until after graduating that he began making films more seriously, bringing with him his understanding of how to work with actors, as well as his love of international films that spoke to him.

“When I graduated, I quickly realized that the auditioning grind was not for me. And so I started making these sketches with my friends so we had things to show that we were acting in. And making those sketches reminded me and rekindled this excitement I had for filmmaking that I had almost forgotten because of those four years of just not doing it,” he explains. “Those sketches led right up to the pandemic. And then in the pandemic, I made my first short, which was like my first time having a cast and a crew and all that stuff.”

Likewise, Brydie O’Connor did not begin her directing career in the film-school model. She attended George Washington University as a history major, actually, but often found herself thinking about screenwriting and volunteering at film festivals on the side.

“I think I was just interested in film as like cultural artifacts, as an accessible way to share a perspective on the world, and a lens on things in the world that affect me and that I’m interested in,” she says. “It just felt like a way to be evangelical and to have conversations with a viewer across time. And just that idea of sharing ideas in this medium was really exciting to me.”

Florrie Burke. Photo: Marisa Chafetz

It was under these circumstances that she found the subject of her film, Barbara Hammer, one of the most important experimental filmmakers of the last 50 years. “I actually wrote my undergraduate thesis on Barbara’s early filmography in the seventies. And at the time, I was living in DC and I couldn’t access any of Barbara’s films. They weren’t showing at any galleries or anything in the area. So, I just reached out to Barbara directly, and she sent me her DVDs, and we were in touch through that, initially. And then I was lucky enough to meet her when I moved to New York,” she says.

O’Connor has been to Provincetown before when she showed Love, Barbara at a 2022 screening at now defunct AMP Gallery, which arranged a full program of work by and about Hammer, who had passed away from cancer three years prior. The film focuses on Hammer’s relationship with her wife Florrie, painting a portrait of a love for the ages, with each woman supportive of the other, each woman as committed to their work as they were to each other.

D’Oyen’s fiction film Lollygag couldn’t be more distinct from it. The film centers on a young queer girl spying on her attractive omnisexual neighbor. Shots of his stunning body clearly objectify him, but D’Oyen’s film is created with a more complex lens than the male gaze, or even the female gaze, allows. His main character is fascinated by her male neighbor, physically, but not because she wants to possess him sexually. There is a complicated relationship. She admires him and wants to have the sexual encounters he’s having, the provocative interludes with women and men that are not restricted to definitions of romantic, platonic, or sexual relationships, specifically. She sees in him something of herself, but also the other, the person she is not, and this takes into account personality, sexuality, and gender.

D’Oyen says the initial seed of the idea came to him when he was all alone in his New York apartment during the Covid-19 lockdown because all of his roommates had gone elsewhere.

“My window looks out across the street into another apartment. And there was this couple that would, every night, go into the bathroom and have sex. And they would press themselves against the glass in this way that—at first I felt very pervy for watching them, but then I realized, through the repetition of their act, and the way that they were pressing themselves on the glass and sort of like putting themselves on display, it was like they knew that they could be seen. And there was this dynamic of watching and being watched,” he explains.

But also, he adds, in hindsight, “The film for me is dealing with the taboo nature of queer adolescence and sexual discovery, sort of this ‘you can look, but you can’t have what you want.’ And I think for me, I would fantasize about the lives that all of my classmates were living. They could have their boyfriends, they could do whatever they wanted, and without any sort of repercussions. But I was forced to live my existence in my head. And I think in the film I wanted to twist it on its head and see like, okay, what happens if you go into the neighbor’s yard, into this fantasy land and it turns out to be not what you expected it to be? It’s gross and decaying and rotting and not the fantasy.”

D’Oyen creates cinematic distance in his film, placing it in an unidentifiable time period, mixing iconography from the past and present, and also using Greek as the language of the girl’s narration, even as the story clearly takes place in America, to further unsettle and displace us. It’s starkly different from the warmth and identification O’Connor fosters in her documentary, which makes it a marvelous combination when shown together.

Both D’Oyen and O’Connor plan to use their residency periods to work on feature-length films connected to the films being screened here. D’Oyen plans to develop a feature-length version of Lollygag, and while O’Connor’s short film is its own self-contained work, her feature project is a full documentary on Barbara Hammer, tentatively titled Barbara Forever, which will focus more on Hammer’s work as a filmmaker.

For her entire adult life, O’Connor says, she’s been working on a Barbara Hammer project. Not the same project, and they’re not the only projects she works on, but there is always a project about the late avant-garde filmmaker going on in O’Connor’s creative and intellectual life. From her thesis, to the short, to now the feature documentary, O’Connor has been deeply connected to Hammer.

“I really admire Barbara as someone who is like an alternative-history-maker. I come from a history background and that’s what I studied. And that was kind of my entry point to Barbara, and so to see her create films in this new way, this way she hadn’t ever seen, you know, a life or community being documented on screen, and to kind of create her own language and to share that with the world and those around her was something that’s just, to this day, so incredibly compelling to me and so inspirational.”

The two films screening in the showcase offer authentic voices that each reflect just a portion of the many threads that make up queer cinematic perspectives. And while in recent years, there have been more and more mainstream fiction films made by LGBTQ directors and featuring LGBTQ characters, there hasn’t necessarily been a great opening up to queer modes of storytelling. It’s one thing for a lesbian filmmaker to make a rom-com or poignant drama about two women, or for gay characters to infiltrate heteronormative narrative films from Hollywood. It’s an entirely different thing to open up the very nature of narrative storytelling to alternative voices who have never been married to the status quo structures and filmmaking norms that make up the dominant cinema. It’s exciting not only for LGBTQ filmmakers and audiences, but for the future vitality of the medium to open up and allow queer innovations that all filmmakers and audiences can benefit from.

The Queer Film Residency program screenings of Love, Barbara and Lollygag is on Friday, April 12, 7:30 p.m. at Waters Edge Cinema, 237 Commercial St., 2nd Fl., Provincetown. For tickets (Free, but must be reserved online) and information call 508.487.3456 or visit www.provincetownfilm.org/cinema.