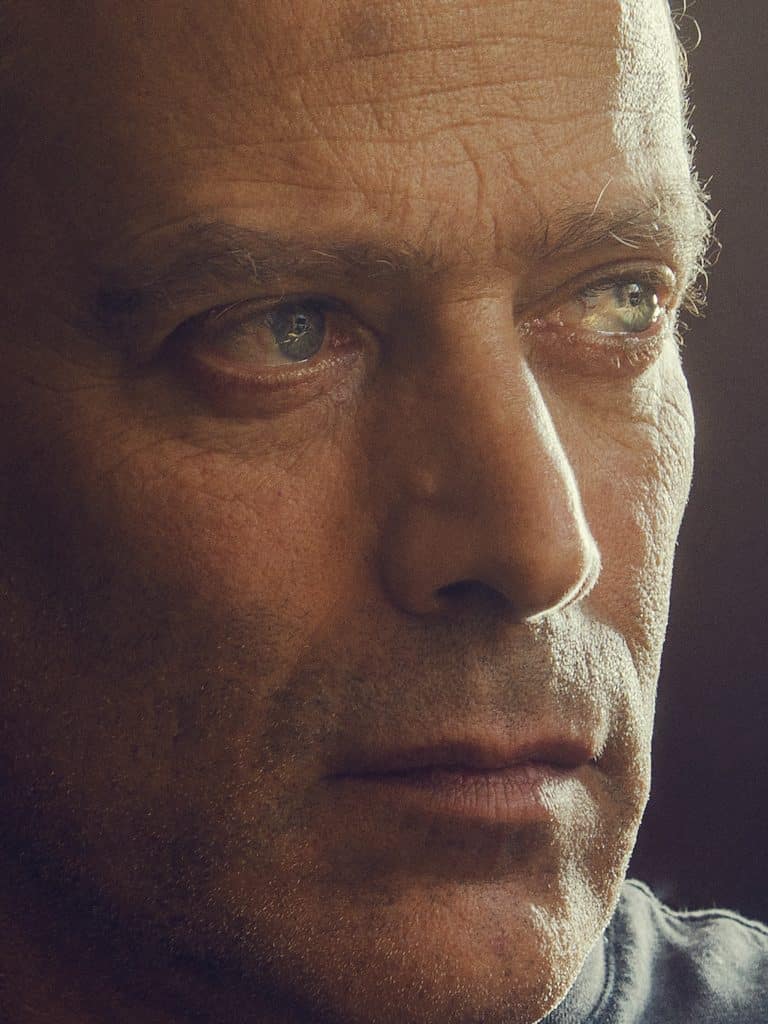

Photo: Chris Anderson

Sebastian Junger’s In My Time of Dying

by Rebecca M. Alvin

By now we are all familiar with the stories of what happens to us when we die. White lights, dead relatives appearing out of nowhere, and then… what? We don’t know because those who go that far into the dying experience either never return to share the details or they are snapped back to us, usually through heroic medical interventions just before whatever comes next.

Journalist and part-time Truro resident Sebastian Junger, author of bestselling books The Perfect Storm, Fire, A Death In Belmont, War, Tribe, Freedom, and his latest, In My Time of Dying, was one of those snapped back to us from the brink, right here at Cape Cod Hospital. And yes, he did see those common things, but for him it was more a question of how those visions happened than why.

In My Time of Dying is not a record of some religious or spiritual awakening. He approaches writing about his own near-death experience from a rare type of aneurysm that burst in his abdomen in 2020 with a research-oriented mind, that of a journalist trying to get to the bottom of things, and relying on science to do so.

“I mean, there’s explanations and there’s stories. And you know when you’re in the realm of explanation, when you can test it, right?” he says, offering as an example the theory of gravity, which can easily be proven by throwing a rock out a window. “When you’re in the realm of story, you can’t test for stories. That means they’re not explanations of how the world works. They’re stories that help us, that help humans, emotionally. And there’s a really basic difference. And some people write books about stories, which is fine. I mean,

the Bible’s a story, right?”

That’s not what Junger was looking for. “If I had wanted a story about what happened, there’s plenty of wonderful, reassuring, comforting, inspiring stories out there that I could go to. I mean, there’s a whole buffet of them out there in the culture, right?” he says. “But I wasn’t looking for a story, yeah. I wanted to know what happened.”

When researching for the book, which combines his first-person account with research, Junger says he found out there’s not a whole lot of variety in what people across the range of identities, geographic locations, genders, and spiritual beliefs experience as they find themselves dying.

“They looked at variants in all kinds of categories—socioeconomic, religious, male, female, older, younger—there wasn’t much. I mean, there was some variation,” he explains. “There’s three or four different sort of experiences. And just like when people fall in love, it doesn’t vary. You might go to this restaurant or that restaurant, but basically, the experience of falling in love with someone is sort of like gay or straight, older, younger, whatever. It’s sort of the same. And so culturally, you know, there’s variations, but I think that the essential human experience is quite the same.”

The explanation, incomplete as it is since there is no way to test theories for what happens after death, took him through the biological, neurological impacts of trauma and extreme blood loss to the theories of quantum physics, which hold that we exist in a multiverse. For him, the most difficult to explain was the appearance of his long-deceased father (who was actually a physicist) above him, as he was dying, but unaware of how bad it really was.

He writes: “I was feeling myself getting pulled more and more sternly into the darkness. And just when it seemed unavoidable, I became aware of something else: My father. He’d been dead eight years, but there he was, not so much floating as simply existing above me and slightly to my left. Everything that had to do with my life was on the right side of my body and everything that had to do with this scary new place was on my left. My father exuded reassurance and seemed to be inviting me to go with him. ‘It’s okay, there’s nothing to be scared of,’ he seemed to be saying. ‘Don’t fight it. I’ll take care of you.’

“I was enormously confused by his presence. My father had died at eighty-nine, and I loved him, but he had no business being here. Because I didn’t know I was dying, his invitation to join him seemed grotesque. He was dead, I was alive, and I wanted nothing to do with him—in fact, I wanted nothing to do with the entire left side of the room.”

Now, four years later, Junger says there was a lasting effect on his relationship to his father. “His appearance above me in that situation was, in some ways, out of character, because he was sort of fully human, you know, with all this sort of parental love and availability. Like, that wasn’t how I experienced him [when he was alive]. He was very much in his head, and that emotional, human part of the spectrum, he didn’t have great access to.”

Clearly, Junger survived, and for that he credits the incredible team at Cape Cod Hospital, as well as the generosity of those who had donated blood in the past because he did lose “an entire body’s worth of blood,” he says. For better or worse, Junger remained surprisingly aware of his surroundings as he was not unconscious, and was not even sedated until later. This incredibly painful experience had a lasting impact, in part because of the —quite accurate—recollections he has.

“It was very confusing at first, and very upsetting,” he says. “I was pretty troubled. I mean, I went from super anxious afterwards that it could happen again to a kind of existential paranoia: Did I really survive? Am I really here, like, some really out-there questions that felt real to me, and that subsided, and, to my surprise, it was replaced by this incredible depression.”

He says prior to then he’d never been depressed and didn’t fully understand the experience of those who had suffered clinical depression. “It turns out that I was going through some classic stages of trauma, and that medical trauma is a known thing, and what was happening to me was quite well known and and so I talked to someone—a professional about it for about six months, and that helped a lot. That actually was very helpful. And one of the things she said was, you know, basically you have to stop thinking about it. Like, we always think that to resolve something, you have to think about it more until you reach this resolution. It’s like no, that’s nonsense. If it’s upsetting, don’t think about it, because you now have worn a little groove in your head, an anxious little loop, and you don’t want to step into that loop, right? Or you’re just going to tell yourself the same scary story over and over and over again.”

As a former war correspondent, Junger has been close to death before, but this time was different. He says it was far more traumatizing than his experiences covering combat, and it changed his thinking about death.

“I’d thought about it and decided nothing happens. Like, the reason we don’t know what happens after we die is that there’s nothing to find out,” he says. “I just assumed that that’s what happens. And it seemed, if you sort of stop to consider the nightmare of unending eternal consciousness without exit, that seemed like the good scenario.”

Maybe we don’t know what happens because it would be unbearable to know that there is no actual end. Maybe it’s our brain’s way of protecting us to keep us in the dark. Or then again, maybe there’s no there there. For Junger, the comforting story of relatives taking you into some other world when you die is not one he can buy into. But, he says, “the explanation offered by quantum physics of some of the stuff we don’t understand, some of the telepathy, some of the occurrences of dying people seeing the dead, you know, and then the enigma of what happens at the quantum level, with superposition and things like that, entanglement, like all that can be tied together by one central proposal, which is that consciousness affects everything and is part of the manifest universe, the physical universe,” he reflects. “It’s overwhelmingly likely that there’s nothing after death, but it’s possible…There’s no way to run the odds. Like, what are you going to base your odds on? I mean, it’s not likely that this exists in the first place. We’re already in the realm of almost infinite unlikelihood that there’s a universe, right? And that we’re in it. So, already, the odds are so wacky that you really can’t describe any likelihoods.”

Sebastian Junger will be speaking at the 1st Cape Cod Book Festival in discussion with author Jacquelyn Mitchard at the Cotuit Center for the Arts, 4404 Falmouth Rd., Cotuit, at 10:30 a.m. on November 2. For tickets ($18 – $23) and information, visit capecodbookfestival.com. His book, In My Time of Dying is available wherever books are sold.