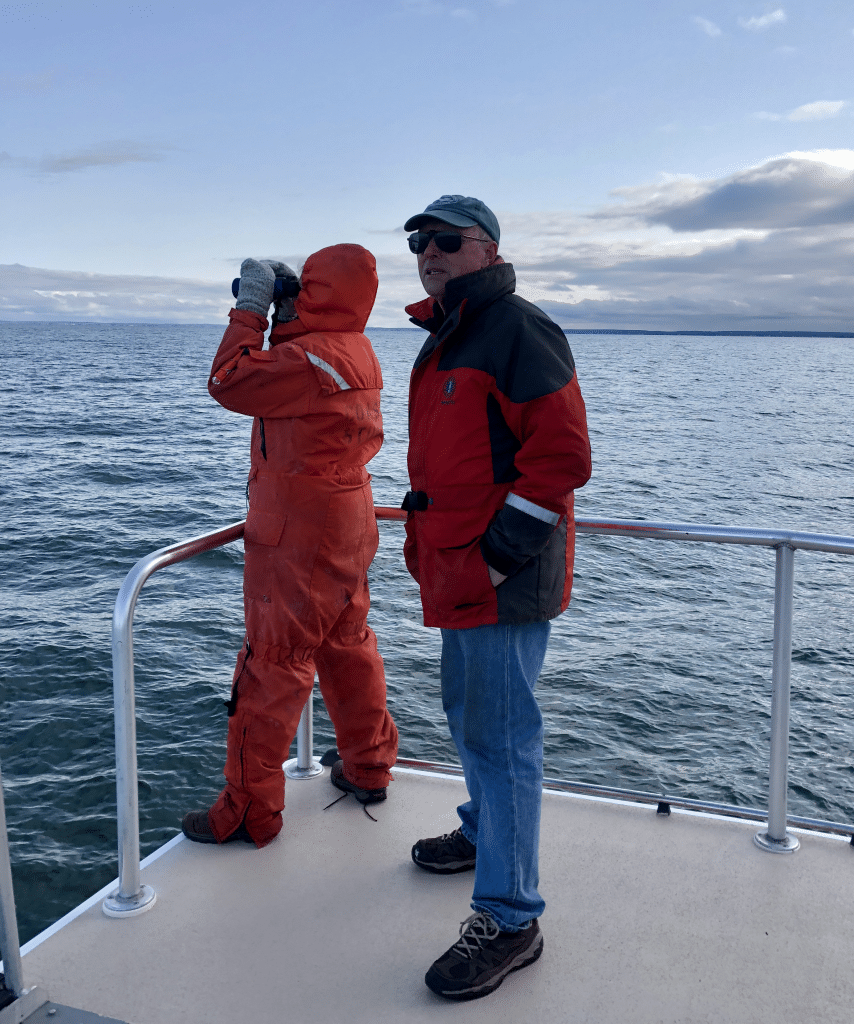

All images courtesy of Center for Coastal Studies

by Lee Roscoe

Charles” Stormy” Mayo says his career resulted from serendipity and luck. The bio-hero retires from the Center for Coastal Studies (CCS) in Provincetown this month, where he has been its program director, senior scientist, and chair of the Department of Ecology over the course of his time there since co-founding it in 1976 with geologist Graham Geise and Mayo’s late wife Barbara Schuler Mayo who suggested it. At the time he’d been thinking of leaving science to build a schooner. (He eventually built it and it is now floating in Provincetown harbor.)

Each of the three PhDs had a distinct interest. Stormy was interested in plankton and fish, Geise in the “physical environment, waves and tides,” and Barbara was expert in benthic ecology, “particularly organisms living in hadal zones, tens of thousands of feet deep,” Mayo says.

“I opposed incorporating [the organization] because it suggested a large white concrete building of three floors with all of us wearing white lab coats. Now it makes sense because we have grown so immensely.” But back then they assembled to teach not-for credit classes informally on the beach. “We came from disparate backgrounds and disparate interests—we figured we ought to expound.” And amazingly, he says, some people who would become significant figures in ocean science came to the classes, including the Center’s current executive director, Rich Delaney.

After Barbara passed away in 1988, leaving him with two children to raise, and Graham moved on (to return later), Stormy operated the Center solo with help from volunteers. “I kept no daily journal that would give us the history,” he says, but sometime in the 1990s through the 2000s, “a number of people saw the center as a potential site for interesting work in other fields.”

Now some 50 staff and a dozen adjuncts study pretty much everything to do with the marine environment from water quality to coastal geography, to fisheries, marine policy, and coastal education. But what Mayo and the Center are most famous for is the study of, and disentanglement of, whales. “The primary reason we work on whales is because of the Dolphin Fleet,” Mayo says. (It still collects data for CCS, and Mayo said it might not exist save for them.) He started out as the only naturalist on the first experimental tour when Captain Al Avellar took his boat to watch sea birds and whales. It changed Mayo’s trajectory. He says, “[this] access to whales was not available elsewhere.” He started out working on humpbacks (“That was the whale-watch whale and still is,” he says), collecting data on individual whales; each humpback’s flukes are like fingerprints. And in the 1980s he began to collect data on individual North Atlantic right whales, whose head bumps or callosities can help “fingerprint” them, and on their ecology, and it “became consuming.” (Colonists named it the “right” whale because it was the right one to catch—slow moving and floating after death.)

Mayo was first to discover a population of the nearly extinct right whales in Cape Cod Bay in the winter, though he stressed that Native Americans and early colonists would have known this population in the past. Fifty to eighty percent of the population (estimated at only 350) come to the bay, he says. They are threatened (as are humpbacks and other whales) by ship strikes, entanglement by fishing gear, climate change, and for right whales, low calving rates. The good news, he says, is that “the work we do feeds into the collective work of all scientists who work on them to make the kinds of stories that help the conservation of the species.” He praised Massachusetts and our Division of Marine Fisheries for working with the Center to provide some of the strictest protection for marine mammal habitat on the planet, shutting down the area when animals are here, mandating that ships cannot go more than ten knots, and fixed fishing gear can’t be placed in the bay.

He has the sea in his bloodlines. His Yankee mackerel fisherman family goes back to the 1600s on the Lower Cape. His father, who captained the rescue boat in the first efforts to free a whale, christened him “Stormy,” because he was born in the middle of a heavy gale. He is likely related to other Mayos who were whalers and famous lifesaving men and admits his immediate ancestors probably took right whales “when they happened to appear close to shore and were easy to harpoon.”

What drives his compassion for the animals; has he completed his mission? “I am passionate and emotional, but I am also fascinated, and maybe that’s the driver for all of this. I certainly care about the conservation of the ocean system, [but it is] intrigue with how the pieces fit together,” which motivates him. Indeed, The Center’s coordinator for Global Whale Entanglement Response, Dave Mattila thinks Mayo’s “greatest contribution has been his unbounded curiosity and what that brings out in others.”

Mayo wonders if climate influences food distribution such as plankton by changing the vertical fluxes of the ocean system, by changing the thermocline; are solar radiation, ocean current, freshwater intrusion, factors in the changing distribution of whales? How do animals make a living and breed within this complex system? If that fascination is the driver and you call that the mission, then the mission is not completed, because there are always questions,” he says, reminding us that “science is about asking questions.”

Mayo will continue to work on other projects such as investigating why some whales choose to come here and some do not. He said, “I don’t pay much attention to my life. I kind of live it. I don’t think a lot about the past or the future, but I spend an awful lot of time indulging in the present. If the ‘good presents’ stack up one on top of another, you have a good past.”

He is proud of the collective work of the Center. “Our work has been a model for others in the field, both in the detailed work on individuals and on ecosystems. The final battles for most species are not necessarily the larger battles of ship strikes nor hunting, but a battle for the ecosystem that supports these animals and us.” There is much more to come.

The Center for Coastal studies will celebrate Stormy Mayo on Friday, May 10, 7 – 10 p.m. at Provincetown Town Hall, 260 Commercial St. The event features live music from SugarBucket, desserts, snacks, and a cash bar, as well as a roast (speakers must sign up in advance). The event is free but registration is required. For more information and to register, visit coastalstudies.org/news/celebratestormy.