by Steve Desroches

It is 36 years ago this month that the Center for Disease Control first identified an unusual outbreak of Pneumocystis pneumonia in five gay men in Los Angeles. On July 3, 1981 The New York Times ran a story with the headline “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals” on page 20. The CDC first called the disease AIDS in 1982, and the following year, after more than 500 Americans had died, it became frontpage news in the national paper of record. So was the beginning of the public consciousness of HIV and AIDS and the epic story of activists fighting not only the largest pandemic of modern times, but ignorance, bigotry, and government apathy that only made it worse.

Photo: Ken Schles

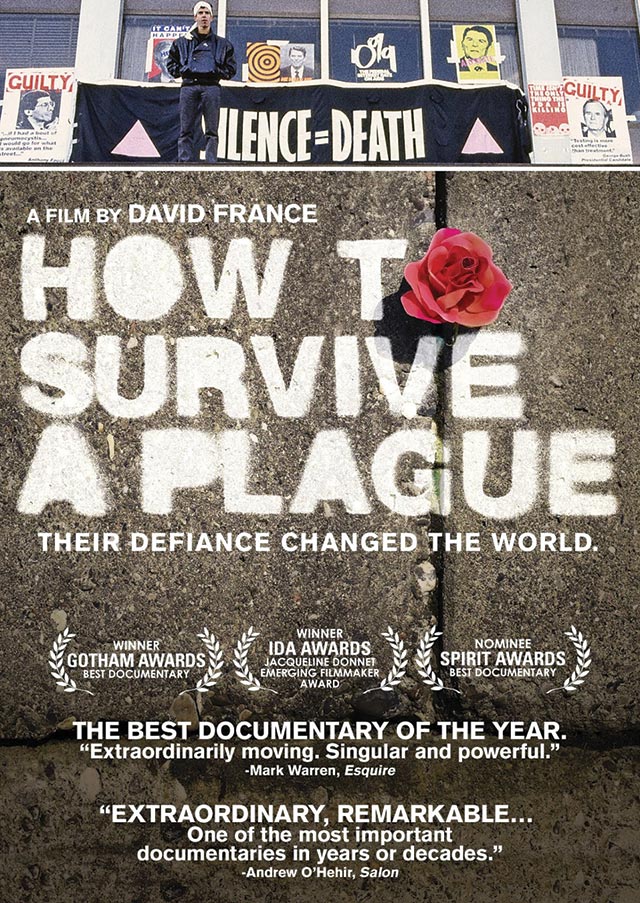

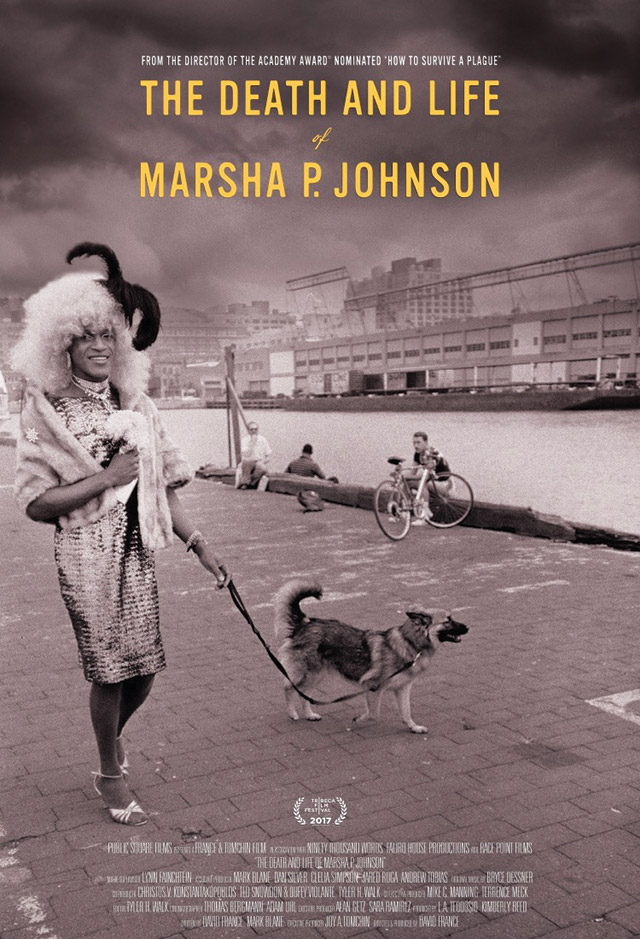

Reporter, writer, and filmmaker David France moved to New York City that summer of 1981 and reported on the earliest days of AIDS as well as the corresponding LGBT rights movement, culminating in his 2012 Academy Award-nominated documentary How to Survive a Plague and the 2016 book of the same name. France will be in Provincetown this weekend to appear with writer and political commentator Andrew Sullivan for a conversation titled Dispatches from the Plague Years as part of 20 Summers at the Hawthorne Barn. Specifically, the discussion between the two accomplished writers will focus on 1981 to 1996, when protease inhibitors became available providing the first successful treatment for HIV and AIDS since the beginning of the crisis. France notes that this combination drug therapy is today keeping 18 million people alive.

“It came very slowly,” says France of the development of the protease inhibitors. “One can only guess if any money had been thrown at it earlier what could have happened. Could we have gotten this in five years? Maybe.”

As a reporter—first for the gay press and then later for mainstream publications such as The New York Times and Newsday—France had a vantage point to observe ACT UP like few others. First reporting on the issues of the day in real time, and now with distance and time, France’s work still captures the frenzy and chaos of those 15 years with his ability to catch a tornado in a bottle through writing. From ACT UP’s meetings at the Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center to protests to interviews with the main players like Larry Kramer, Peter Staley, Ann Northrup, Mark Harrington, Iris Long, Bob Rafsky, Bob Barr, and more, France was reporting from the front lines. He was also present for one of the most shocking and controversial, and perhaps effective, acts of protest in American history: when on December 10, 1989, 4,500 ACT UP and WHAM (Women’s Health Action and Mobilization) protestors gathered outside St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York to oppose Cardinal John Joseph O’Connor statements against safe sex education, condoms, homosexuality, and abortion. Several dozen protestors went inside for what was initially supposed to be a silent protest but erupted into shouts and disrupted the mass in progress. Condemnation was swift and the action shocked the nation.

“It caused a wild backlash, including from every gay rights group in the country,” says France. “ACT UP made no friends that day. ACT UP scared people; people were more afraid of them. They realized fear was an interesting tool. Now they had everyone’s attention.”

Indeed they did. And while other protests and actions garnered attention – like the dumping on the White House lawn of ashes of people who died from AIDS or unrolling a giant condom on rabid homophobe North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms’ home – ACT UP grew in influence and scope. The men and women of ACT UP effectively got the United States to respond to the AIDS crisis on every level. And France, along with Sullivan, can tell that story honestly and clearly, not shying away from warts and all.

“Oh, yes, Obama was a student of those things,” says France. “And rightfully so.”

Twenty Summers presents Dispatches from the Plague Years featuring David France and Andrew Sullivan in Conversation Friday, June 2 at 7 p.m. at the Hawthorne Barn, 29 Upper Miller Hill Rd. For tickets ($25) visit 20summers.org; for information, call 508.812.0278 or e-mail info@20summers.org. There is no parking at the Hawthorne Barn or on Miller Hill Rd.