by Rebecca M. Alvin

Top Image: Photo: Dona Ann McAdams

After the initial shock of the whole world going into lockdown mode in the spring of 2020, many people began to look at their lives and their new access to that most important resource: time. The impulse to be “productive” grew, and in between Netflix recommendations and obsessing over COVID-19 data, Facebook feeds were loading up with posts about friends learning new languages, reading Proust, growing gardens for the first time, writing novels, redecorating their homes, learning to craft-brew or sew or play an instrument.

In the arts community, this need to utilize the time that so often eludes us as artists working in a capitalist system that frequently devalues our work was particularly resonant. Finally, the world had stopped for us to catch up, so what would we do with this time? What brilliant creations could we make, should we make?

For artist and writer Karen Finley, just the word “productive” itself is problematic. “Instead of saying ‘productive,’ I’m going to say I’ve been very ‘generative,’” she says.

Finley, who will receive the Rose Dorothea Award from the Provincetown Public Library this Friday, came into the limelight when she and three other artists (Holly Hughes, Tim Miller, and John Fleck)—known as the NEA Four— had their National Endowment for the Arts funding revoked in 1990 on the grounds that the subject matter of their works was obscene. Finley was the named plaintiff when the case went to the Supreme Court in 1998, where it lost, and consequently the NEA stopped funding individuals. But Finley has continued her provocative, compelling work, never afraid to call attention to the issues that matter to her, particularly in the realm of human bodies, sexual identity, and freedom of expression.

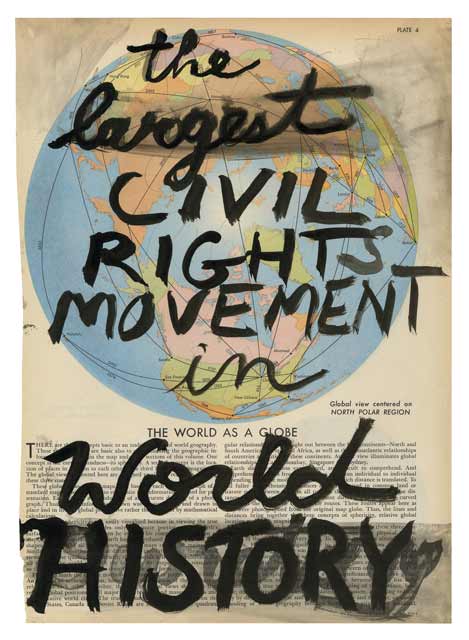

Working in performance and visual art, Finley is also the author of nine books, including the groundbreaking Shock Treatment (1990; reissued in 2015) and her most recent one, Grabbing Pussy (2020), which as you might suspect, takes on former President Donald Trump and the implications of his presidency, which continue to permeate the public sphere in dangerous ways. That book is abstract and poetic, beautifully articulating the rage, frustration, and hypocrisy of our current social and political landscape, a startling example of her political engagement as well as her artistic sensibilities as a writer.

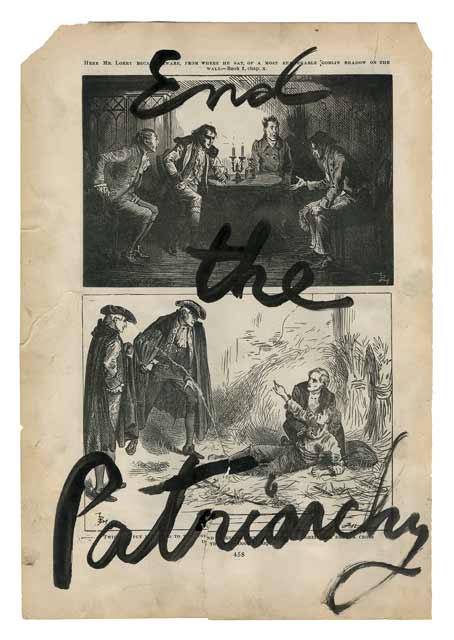

Finley has little tolerance when questioned about art’s influence in the world, whether or not it’s enough, whether or not it can change hearts and minds. It isn’t that she doesn’t understand the question. It’s that it is asked of artists so frequently and presumes a kind of ineffectiveness of artistic output seeking to stimulate sociopolitical change. The presumption itself is problematic. “I think that’s a very large question. I think that artists are typically blamed that what they’re doing is not enough, so that question is to say that my work then is disappointing…That question is based on capitalism or a certain form of what that is,” she says.

“If you can even think that in Afghanistan, the $2 trillion in military might could have been artistic might. Or that on CNN all these things that we’re seeing, if there were even five minutes a day on culture or what an artist is doing, what a poet is doing, what the influence would be… I guess I question the idea of how do we monitor what influences?” she explains.

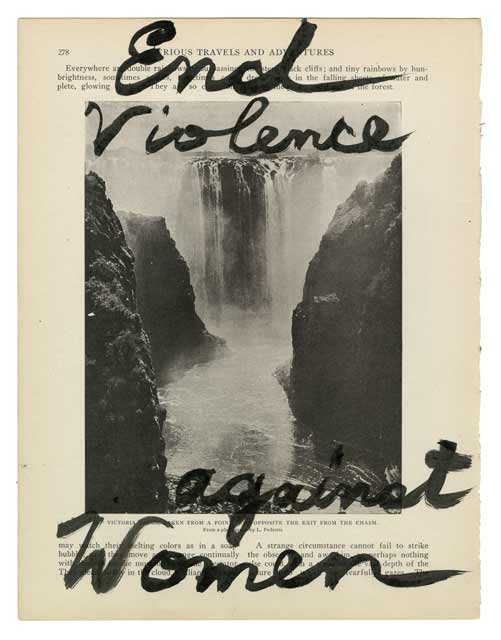

Here we are in the midst of a turbulent decade in which the Supreme Court has not touched Roe v Wade, technically, but has disregarded it by allowing the State of Texas to ban all abortions occurring after six weeks of pregnancy, about the time when most women are just taking a pregnancy test to even know if they are pregnant. It came as a sort of gut-punch to many women when the Supreme Court allowed the Texas law to stand with barely any comment on it. How is it that we are still arguing for the basic rights of women to own and control their bodies in 2021?

“I think that your question is so important. I mean, yes! Not just 20, 30, 40 years ago, but going back for thousands of years, so it is in the same place. I think the one thing that’s different is that the younger generation, I just feel that there are many more people who understand the issue,” says Finley. “I’m very despaired about it. I do a lot of visual and installation work, and I’m really trying to be figuring out what are motions, or what is it that we can do as artists here for Texas? That’s what I’m thinking of. So for me, I don’t usually spend time always looking and thinking like I’m spilled milk—’Oh my goodness, this is still going on here?’—Instead, my energy is thinking what is it that we can do now? How can we mobilize? What’s happening in Texas? What kind of imagery can we do?”

Despair, disappointment, and frustration are rampant among socially conscious individuals who see rollbacks of previous victories coexisting with amazing progress in other areas. But Finelyis not entirely surprised.

“I always felt that this was a possibility. I’m not a historian, but I have observed in history that there are these tensions or conflicts that happen and it’s very, very disturbing. What is one supposed to do then, just close the door and call it a day? No. You just have to continue to get out and fight all over again,” she explains.

Looking at the historic Supreme Court case back in 1998, Finley also offers another perspective on what might come out of this moment. While that case, she says, was definitely about shutting down expression of identity—sexual identity in particular—things have changed for the better since then. “After that loss, things started also then changing in society. I mean no one would have thought that gay marriage [would be legalized]… but that happened. So I wonder also in observing what is happening now, will there then be this incredible movement to actually even change for the good or betterment for women? You know, for all bodies, because it also has a relationship to what’s happening now with trans bodies, especially youth not being able to have medical service or medical care in some states, like in Arkansas. So there’s a real relationship with that of controlling bodies.”

Finley is honored to be receiving the Rose Dorothea Award, which is given annually by the Board of Library Trustees of the Provincetown Public Library “to a person with a strong connection to the Outer Cape who has made a significant contribution through the written word.”

She has been coming to Provincetown, she says, since 1985 and has written books here, created works here, shown and performed here, previously belonged to the now-closed DNA Gallery, and has engaged in the community in so many ways.

“I’ve been coming there a long time. What’s that, 35 years? And I would come up and stay at little bed and breakfasts,” she says. “I mean maybe there was a summer here or there that I didn’t go, but, like even just this year, it was so wonderful for me. And actually the work that I made there is in a show in London now. So it’s always been very generative for me… It’s just a wonderful place for me.”

Asked what she’s working on currently, Finley casually offers a litany of descriptions of projects, shows, books she’s doing, a collection of her writings on AIDS, and future activities. Told she actually is quite “productive,” Finley laughs and says, “I try every day to live a creative and poetic life. And that means that it’s about observation, of always being attuned to what is happening, observing, looking, spending time with and reflecting. And I try to have that in my life… An artist needs a certain amount of time and space to create. And so that’s my form of rebellion.”

Karen Finley will receive the Rose Dorothea Award and give a reading at the Provincetown Public Library, 356 Commerical St., on Friday, September 17, 6 p.m. as part of the Provincetown Book Festival. There will also be a reception afterward. Masks and proof of vaccination status are required for this event and all other Book Festival events.For more information call 508.487.7094 and to reserve a free ticket visit provincetownbookfestival.org.