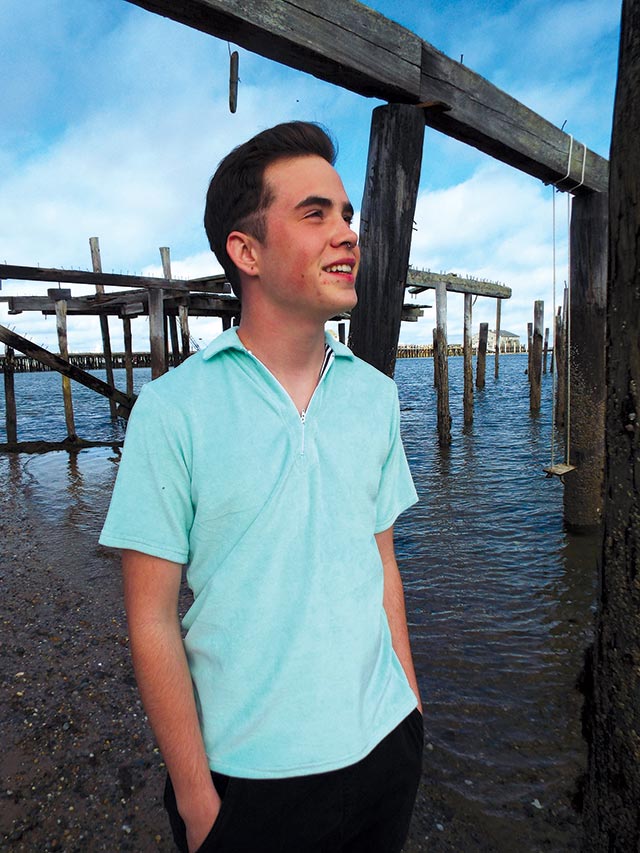

Teddy Lowery

by Steve Desroches

Teddy Lowery walks into Far Land Provisions wearing a navy blue t-shirt that says “Make America LGBTQ Again” and a multi-colored print cardigan sweater, which he wraps tighter around himself hiding the play on the Trump campaign slogan. The Bossier City, Louisiana, native isn’t covering the message intentionally, but rather because he’s cold. Really cold. It’s 86 degrees back home, and for it to be 50 degrees in May feels more like winter to him than spring. But he does confess that if he wore that shirt at home there would definitely be dirty looks, and possibly worse.

Lowery is the first to arrive in Provincetown as part of the Summer of Sass, a program developed by resident and comedian Kristin Becker to connect young LGBTQ adults ages 18 to 24 with host families on the Outer Cape to let them experience a community that values them for who they are. He’s only been in town for four days, but is taking to Provincetown quickly.

“The town is so quaint and it’s so cold here,” says Lowery. “I saw two girls holding hands walking down Commercial Street this morning. That was pretty cool.”

Provincetown has of course long been a refuge to the outsider, especially to the gay community. And Becker wanted to be more active in bringing LGBT youth from some of the most oppressively conservative parts of the country to Provincetown to be a part of this town’s unique culture. Born in Buffalo, New York, but raised in Shreveport, Louisiana, which is across the Red River from Bossier City, Becker understands all too well what life for LGBT people can be like in the South.

In the spring of 2016 Becker kicked off the “Loosen the Bible Belt Tour” traveling the Deep South with Pastor Jay Bakker, the pro-gay-rights son of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker. A lesbian comic and an evangelical Christian minister taking to the stage together in places like Montgomery, Alabama, and Oxford, Mississippi, attracted quite a bit of attention to say the least. Over the course of that tour Becker met local LGBT activists planting the seed for the Summer of Sass.

“As lesbian as it sounds I just put it out in the universe,” jokes Becker. “I really thought it was the perfect concept.”

Becker wrote to several of her contacts throughout the South about her idea and received instant positive feedback from several, including Adrienne Critcher, political director of People Acting for Change and Equality (PACE), an organization working for LGBT equality in northwest Louisiana. Critcher founded PACE over a decade ago after her son came out as gay and faced intense homophobia in Shreveport. Lowery had never heard of Provincetown before Critcher told him about both the town and this new venture. He was instantly intrigued and interested.

Now 18, Lowery came out when he was 13 years old, just before his freshmen year of high school, which he describes as “the most miserable year of my life.” Taunts of “faggot” and harassment were daily occurrences for him at Parkway High School. He failed physical education as he skipped the class often due to anonymous death threats saying he’d be killed if he showed his face in the locker room. A lot of the “yee-yee boys,” a nickname at his high school for rednecks, drove their pick up trucks flying the Confederate flag off the back, but when a classmate put a rainbow flag sticker on their bumper, the school made them remove it as it was seen as “pushing their lifestyle on others.” Completing enough credits he graduated early this January to leave all of that behind. Now, in his first week in Provincetown he’s already begun a job at the Human Rights Campaign Action Center and Store and will soon have another gig at Coffey Men, a Commercial Street men’s clothing store.

“I was really just looking for a change,” says Lowery. “Kind of running away from the dirty South. I got this awesome opportunity.”

A big part of the motivation for starting the Summer of Sass was the persistent labor shortage in Provincetown. For many decades, Provincetown has relied on imported labor from elsewhere, now usually from Eastern Europe and Jamaica. Concerns that Congress will limit the visa programs the town relies on have been a consistent worry for years now, and even when caps are lifted many jobs still go unfilled in Provincetown. Finding employment wouldn’t be an issue, says Becker. But what about housing? It’s largely gentrification and lack of affordable housing that has driven out a working and middle class on the Outer Cape, and kept many young Americans from coming here to work for the season in the first place. So Becker reached out to the community for host families, or for those willing to rent a room at a reasonable rate. Understanding that not everyone could afford to do so, Becker nevertheless felt this is a case where Provincetown as a community could show whether the long-standing reputation as a “safe harbor” was still the case.

“For as much as we talk about who we are as a community, we have to ask ourselves do we live up to those values,” says Becker. “Is it all just lip service or are we a community that actually lives the values we proclaim to have?”

So far, offers for housing are slow, but steady, as are other offers of help, like volunteer mental health counseling as well as those eager to interview for employment and support from the Provincetown Community Compact, the philanthropic organization founded by Jay Critchley that produces the Swim for Life and other community-building projects and fundraising events. Lowery is living with Rod Vaughan, well known as a banjo musician, singer, and former bartender at the Porch Bar, and now working for the United States Postal Service. A native of West Plains, Missouri, in the Ozark Mountains, not far from the Arkansas border, 45-year-old Vaughan instantly recognized the stories he was hearing via Becker.

“I’m from the South and I know what it’s like,” says Vaughan. “I came out at 18 or 19. There was no one to talk to about that. I told a friend and she said to me, ‘When you get AIDS I’ll never speak to you again.’ I had to leave.”

Plans are to roll out the Summer of Sass slowly as interest increases. And things are kept rather informal, with Becker acting as a conduit for those who contact her. All prospective hosts go through background checks, and while the program is for young adults, all are asked to act as mentors for these young people, many of whom have experienced trauma, familiar to many in Provincetown.

Again, its starting slow and small to see how sustainable the idea is and how much community support it can maintain. The second participant, Sam Mitchell from Tyler, Texas, arrives this week to live with Bethany Gregory and her family in Truro. As a transgender young man, Mitchell continually faces bullying and isolation in his East Texas hometown. The fear is real, as the murder rate for transgender people each year reaches a new high surpassing the previous year’s numbers, with many of those crimes being committed in the South. Becker originally said no, as Mitchell is only 17, with a birthday coming up in August. But his stepmother pleaded with her, saying he needed above all else to be somewhere he would be accepted, just to feel what that felt like.

“It broke my heart,” says Becker hand to chest with teary eyes. “How do you say no? I just couldn’t say no. We can’t say no.”

For more information or to get involved with the Summer of Sass visit loostenthebiblebelt.com.