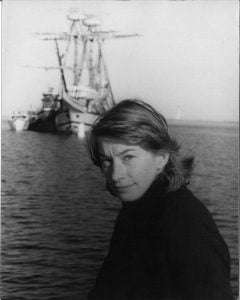

The Story of Katherine Ann Power

by Steve Desroches

In 1970 Katherine Ann Power went from being an honors student at Brandeis University to a fugitive on the FBI’s Most Wanted list. It was a rapid and furious journey. Born and raised in Denver, Power was a Girl Scout, the valedictorian of her Catholic high school where she won the Betty Crocker award for cooking. When Power arrived on the Waltham, Massachusetts, campus in the fall of 1967, she quickly turned her political passions into action working with Students for a Democratic Society, protesting the war in Vietnam, and organizing for civil rights. So far, the story sounds familiar, even ordinary: a young undergraduate finding her voice and place in the world and working to effect change. But things took a violent turn.

Power and her roommate Susan Saxe, along with fellow student and Vietnam veteran Stanley Ray Bond, devised a plot with William Gilday and Robert Valeri (who, like Bond, were former convicts), to arm the Black Panthers and fund future anti-war activities. On September 20, 1970, they robbed the National Guard armory in Newburyport, Mass., stealing 400 rounds of ammunition and weapons, and then set the building on fire. Three days later they robbed the State Street Bank & Trust in Brighton. Boston police officer Walter Schroeder was first on the scene and was shot by Gilday, later dying from his wounds. Power drove one of the getaway cars. While the three men would be captured shortly thereafter, Power and Saxe escaped arrest. Saxe was caught in 1975 and served five years in prison. Power was a fugitive for 23 years, assuming the alias Alice Louise Metzinger, and living a rather regular life in Oregon before turning herself in to authorities in 1993.

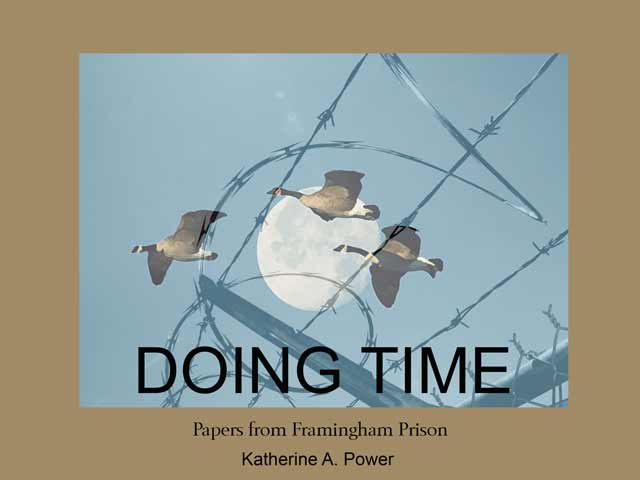

Power ultimately served six years in prison after pleading guilty to two counts of armed robbery and manslaughter. How did she, as someone who was so committed to peace and equality, take part in a violent action that resulted in someone losing their life? How does that happen? It’s something that Power still reflects on and will be addressing when she reads at AMP this week from her book Doing Time: Papers from Framingham Prison and the memoir she is writing titled Surrender: A Journey from Guerilla to Grandmother, a work she wrote much of here in Provincetown over several years.

“I really believe the politics of rage arose from a sense of powerlessness and to act louder than our own grief,” says Power. “There had been the shooting at Kent State and Jackson State. It seemed like a no going back moment. There were frequent bombings of recruiting offices. There was the bombing at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. People began acting out of outrage. After all, that was what our government was doing to us.”

Power’s story has taken on that recognizable romanticism in our culture, even becoming the inspiration for an episode of Law & Order guest starring radical lawyer and activist William Kunstler. But she’s a real person, with a full range of experiences and emotions. It is of course hard to reconcile violent acts and the reasons each perpetrator may have in explaining themselves and taking responsibility. Life on the run felt like being hunted, says Power. Even once she moved to Oregon and found more stability, not having to move constantly, keep a job for no more than a year or so, even having a social security number as well as having a son, her past eventually clouded out everything.

“I really believe you cannot have moral authority with your children without telling them about your life,” says Power.

As she examined her life and herself in all its totality, she not only made connections between her political radicalization and her actions, but also her personal life. Her father had severe depression and mental health issues that made him violent, says Power. She felt she was at times the protector of her family, and that role morphed into a sense of duty, but this time in fighting the abuses of the U.S. government, she says. She herself had episodic depression, which eventually became so severe she didn’t leave the house and stopped speaking. She eventually went to an all women’s therapy group where they were asked, “Where is your soul in all of this?” From then on she knew she needed to turn herself in.

No matter how self-aware Power has become about the events of her life and no matter how much she now advocates for peace and non-violence, there will be a substantial number of people who will only see her as someone partially responsible for a man’s death. Claire Schroeder, Walter’s daughter and herself a police officer, at the time of Power’s surrender said to the New York Times, “I was a senior in high school and I thought the Vietnam War was wrong but I don’t recall going out and robbing banks and killing people to express myself.” And then adding, “My father’s murder seems to have had a great deal more impact on my family’s life than it has had on hers.” Later in life she said that while Power may have changed, their lives intersect at the murder of her father, and always will, but that she wishes Power to have the life she wants to have. To some she is a criminal, others a reformed, productive member of society.

“One of the things I have learned is that I have earned my karma,” says Power. “And that’s a price of my karma. My story has also inspired people and that’s a part of my karma, too. “

Katherine Power will read at AMP, 432 Commercial St., Provincetown, on Wednesday, October 10 at 4 p.m. The event is free. For more information call 646.298.9258 or visit artmarketprovincetown.com.