by Steve Desroches

It took a little over two weeks for America to start laughing again after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. As Americans stumbled through the haze of trauma, shock, and grief, laughter seemed not just distant, but perhaps also a cultural casualty of that awful day. The following week Graydon Carter, the editor of Vanity Fair, wrote a premature obituary declaring the death of irony. So, too, did Roger Rosenblatt in Time magazine and many others in the media. Those who observe and comment on our culture didn’t see a clear path toward how comedy would recover and said so almost in panicked tones. At its absolute best comedy can heal, and laughter is a necessary salve soothing the tragedies of life. We need to laugh. But who was going to crack the first joke to a nation still in tears.

It was on September 29 that two comedy institutions tried to get America laughing again, with very different results. Saturday Night Live began its 27th season with a solemn, cold open featuring members of the New York police and fire departments and then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani declaring the city would begin to return to normal. When Saturday Night Live producer Lorne Michaels ask Giuliani, “Can we be funny?” the Mayor quipped “Why start now?” And the audience laughed. But just a few blocks uptown at the Friar’s Club, at a roast of Hugh Hefner, things went differently when comedian Gilbert Gottfried took to the dais and joked, “I have to leave early tonight, I have a flight to California. I can’t get a direct flight. They said I have to stop at the Empire State Building first.” The audience hissed and booed, and someone yelled out “Too soon!”

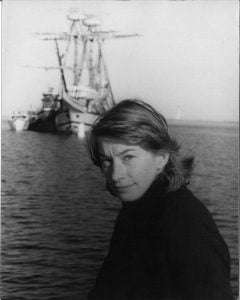

Tragedy plus time equals comedy. That old adage rings true, especially considering how jokes about past horrible events roll off the tongue, be it the Lincoln assassination (Other than that, how was the play, Mrs. Lincoln?) or the Hindenburg disaster with people yelling out “Oh the humanity!” for the littlest thing, proving irony is hard to kill. Timing is everything in comedy, in more ways than one. And everybody has their own internal clock as to when a joke is funny, be it a few days or years or never. The bigger the taboo, the bigger both the laughs and the controversy, something journalist Julie Seabaugh sees all the time, as her beat is exclusively comedy. And she explores just how far you can push comedy in an upcoming documentary Too Soon? The Comedy of 9/11, an excerpt of which will be shown at the new End of the Earth Comedy Festival this weekend.

“It was a big moment,” says Seabaugh about those comedic moments after September 11. “It was pretty pivotal, especially for comedians.”

Based in Los Angeles, Seabaugh writes about comedy in all its formats, but primarily live performance, covering those who make people laugh for a living and turn it into an art form. Those comics who can successfully ride the edge are masterful to watch, and in particular, those who can make people laugh using something as gut-punchingly tragic as 9/11 are fascinating. It’s why when her filmmaker friend Nick Fituri Scown asked her if she’d like to make a documentary about this most verboten of topics she said yes, coming on as producer. The 20-minute sneak peek screening of the doc focuses on the satirical newspaper The Onion and its first issue after 9/11. The staff of The Onion celebrated their move from Madison, Wisconsin, to New York City with a party on September 10 of that year. That first New York City based issue was their debut to a city deep in mourning with headlines like “U.S. Vows To Defeat Whoever It Is We’re At War With,” “Rest of Country Temporarily Feels Deep Affection For New York,” and “Hijackers Surprised To Find Selves in Hell.” They, too, initially received messages of “too soon,” but followed by many more of gratitude for breaking the sadness and tension smothering New York.

Regardless of the topic, comedy is especially hard in these times of cancel culture and keyboard warriors. A joke can end someone’s career now, or at least derail it, even if the comic themselves is intimately tied to the tragic source material. Saturday Night Live cast member Pete Davidson was seven years old when his father, a New York City firefighter, was killed on 9/11. At a Comedy Central roast of Justin Bieber he made jaws drop when he joked, “I lost my dad on 9/11, and I always regretted growing up without a dad, until I met your dad, Justin. Now, I’m glad mine’s dead.” For that joke, and others, he caught a lot of flack. He responded that he jokes about what’s most painful until it doesn’t hurt anymore. The Internet can frequently have a toxic effect on comedy as it removes all context, intention, and tone, says Seabaugh, as those who comment on a joke often weren’t even at the show. It’s like reviewing a play you never saw. All that’s left can be uninformed sanctimony.

“Comedy in part is something you need to experience live in the moment with someone connecting with the audience,” says Seabaugh. “A lot of the people who say a joke is inappropriate the most have never been in a comedy club.”

There is no other journalist in America who documents comedy more than Seabaugh. Author of Ringside at Roast Battle: The First Five Years of L.A.’s Fight Club for Comedians, Seabaugh grew up on a farm in rural Missouri without cable television. As a journalism student at the University of Missouri she first got the idea to be on the ha ha beat when stand up comic Dave Attell came to campus and she and her friends took him to The Heidelberg, a favorite haunt for the journalism students, for Jägermeister shots. The rest of the night went as one might expect it would with Jägermeister as fuel, but both her head and stomach hurt the next day, one from drinking and the other from laughing.

“I woke up the next morning on my friend Dan’s floor,” says Seabaugh. “And I thought, ‘I like this comedy thing.’ It’s free speech, and all you need for comedy is a microphone and a brain. You can have an audience where people disagree on things, but laughter is unifying. It gives me a certain optimism. In comedy you can talk about anything, often those things that people on an everyday basis find difficult to talk about.”

The End of the Earth Comedy Festival presents an excerpt of the documentary film Too Soon? The Comedy of 9/11 followed by a panel discussion featuring Julie Seabaugh on Saturday, October 12 at 3 p.m. at the Pilgrim House, 336 Commercial St., Provincetown. Tickets ($15) are available at the box office and online at pilgrimhouseptown.com. For more information call 508.487.6424.