Rebecca Hutchinson’s Flower Sculptures

by Rebecca M. Alvin

Top Image: Rebecca Hutchinson’s Five Part Bloom, fired and unfired porcelain paper clay, handmade paper, organic material, 68” x 68” x 12”, 2017. (Detail) Photograph by Carly Costello, from the permanent collection of Lawrence & Marie Wolin.

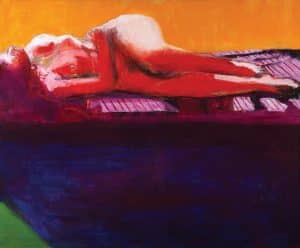

Flowers are underestimated. But they are actually layered in their meanings. They can simultaneously evoke funerals and weddings and new life and birthdays and prom corsages and romances and apologies and love and loss and regret. They can be used to signify femaleness, reproduction, and sex, and yet they are fit to grace any table in our sharply divided country, without a hint of controversy. But beneath the pretty and conventional veneer, in the right hands, flowers can be extremely potent messengers, as they are in the Art of the Garden: Double Bloom exhibition at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum (PAAM), which pairs the work of Joan Snyder and Rebecca Hutchinson and was curated by Cherie Mittenthal.

The first thing you’ll notice about Hutchinson’s wall sculptures in the show is the tension between the wildness of her paper and clay flowers and the structure of the frames out of which they seem to grow. A flower garden mixes together these ideas of chaos and order; plants are sown in lines, but they blossom into great bursts of life that cannot be contained—not really—even within the willow-branch lattices and frames they push through. As Hutchinson puts it, it’s “determined growth that moves beyond structure.”

Hutchinson’s sculptures are magnificent, evoking the beauty of flowers in a dense garden of roses, wildflowers, and even tulips, but in a subdued, pretty palette. Within these pieces there is a commentary however; the tensions between natural wildness and containment are palpable.

“There is a sense of order with the grid format. The wood is gridded, that gives me a structure to build on. But, conceptually the work is about embracing the defiance of order, and the growth patterns defy the section of the wood,” Hutchinson explains. “So there might be three sections of wood made, or four sections of wood made, but the growth pattern defies those boundaries, and that is intentional. Conceptually, that is what has interested me in the last several years, that there’s a homogeny, there’s a sense of… collective harmony to the overall piece despite that the framework is made of three or four or five different sections of wood structures.”

Hutchinson’s work hangs alongside those of Joan Snyder, whose mixed-media paintings also incorporate materials that push them into three-dimensional space and play with this idea of geometric lines coexisting with the chaos of nature. For example, in her Rose Grid (2014), she paints a grid of 16 boxes— four across and four down—defied by the organic, swirling, unruly patterns drawn within them, some of which even boldly cross the gridlines. Both artists are focused on flowers and gardens, however it’s not only a thematic connection.

As Hutchinson puts it, “For me what’s important is not just the imagery of the bloom activity, it’s kind of the raw, direct choice of material and the way material is used,” she says. “It’s like confident and raw and bold in both of us.”

For Hutchinson, the materials and the processes by which she creates these works are important and connect strongly with her artistic goals. Each piece is constructed of various materials she’s harvested, as well as ceramic or clay, combined together in a layered process that’s important to the work itself.

“All of the materials are either ceramic or handmade paper, [and] I harvest willow from my property, and that’s what the woodworking is. There’s always a woodworking frame that I build on,” she explains. “I’ll just share that harvesting is a real key component to the philosophy of the work, harvesting with some sensitivity. So what I’m doing is I’m choosing fast-growing wood, which is the willow, and then the handmade paper is also involved in harvesting. And I’m going to thrift stores, and I’m choosing 100% natural fiber old clothing. So blue jeans and flannel shirts, linen shirts, or perhaps stained and torn table linens, and all of that is cut up and put into my papermaking beater.”

The process of making paper from the pulp is a complex one, but this pulp is not only made into the paper used in her sculptures, it is also incorporated into the clay, making it much more lightweight and therefore better suited to these hanging sculptures. It is only after the materials themselves are made that Hutchinson begins actually making the flowers we see.

“I love not only gardening, but also observing how plants thrive, how they meet a boundary, how they defy the boundary, how they deal with excessive aspects in the environment,” Hutchinson says.

As the child of two parents who were scientists, Hutchinson stresses the importance of observation in her process, as well as a rich understanding of her materials. “Looking at you know, species, how they build nests; it’s a combination of mud and fiber, it’s collected material from site, or often I say, from ‘the vernacular,’” she explains.

All of this amounts to work that is not only about process and form, but also translates to a deeper meaning that is intrinsically connected to her choices in material and the blending of those materials.

“The sculpture has evolved, in all honesty, in scale and in all aspects: in my investigation and experimentation of shape, of my sensitivity to the concept of defined boundaries, particularly right now where we are all overly involved, politically, in thinking about siloed activities and homogeny. And I’m interested in the blend of hybridity. So that blend of hybridity becomes also socially relevant to me,” she says.

Hutchinson is a professor of ceramics at University of Massachusetts—Dartmouth and she has also taught locally at Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill, where she and Snyder were first exhibited together some years back. Her work has been shown widely, including in the Taiwan Ceramics Biennale, the San Francisco Museum of Craft and Design, the National Museum for Women in the Arts, SOFA (now Intersect Chicago, represented by Duane Reed Gallery), the Daum Museum of Contemporary Art, the Vendrell Biennale (Spain), the Danforth Museum of Art, the Lowe Museum of Art, the Canton Museum of Art, and the Fuller Craft Museum.

Art of the Garden: Double Bloom is on exhibit at PAAM, 460 Commercial St., Provincetown, through July 18. To reserve a timed ticket or for more information call 508.487.1750 or visit paam.org.