by Rebecca M. Alvin

When in 2020 the whole world basically shut down because of a fast-spreading virus, it was hard not to notice the timing as everyone from Plymouth to Provincetown had been planning ways to commemorate that year the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing on these shores, bringing with them disease and eventual destruction to Native communities. While the folks in Plymouth worked on their own commemorative projects, here the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum opened a new exhibit, OurStory: The Complicated Relationship of the Indigenous Wampanoag and the Mayflower Pilgrims, designed by Wampanoag creators from Mashpee that told the story of the first encounters with Europeans from a Native American perspective. Signaling a larger change and progress in correcting the historical record, the Museum installed it as a permanent exhibit, not just a one-time show at this key moment.

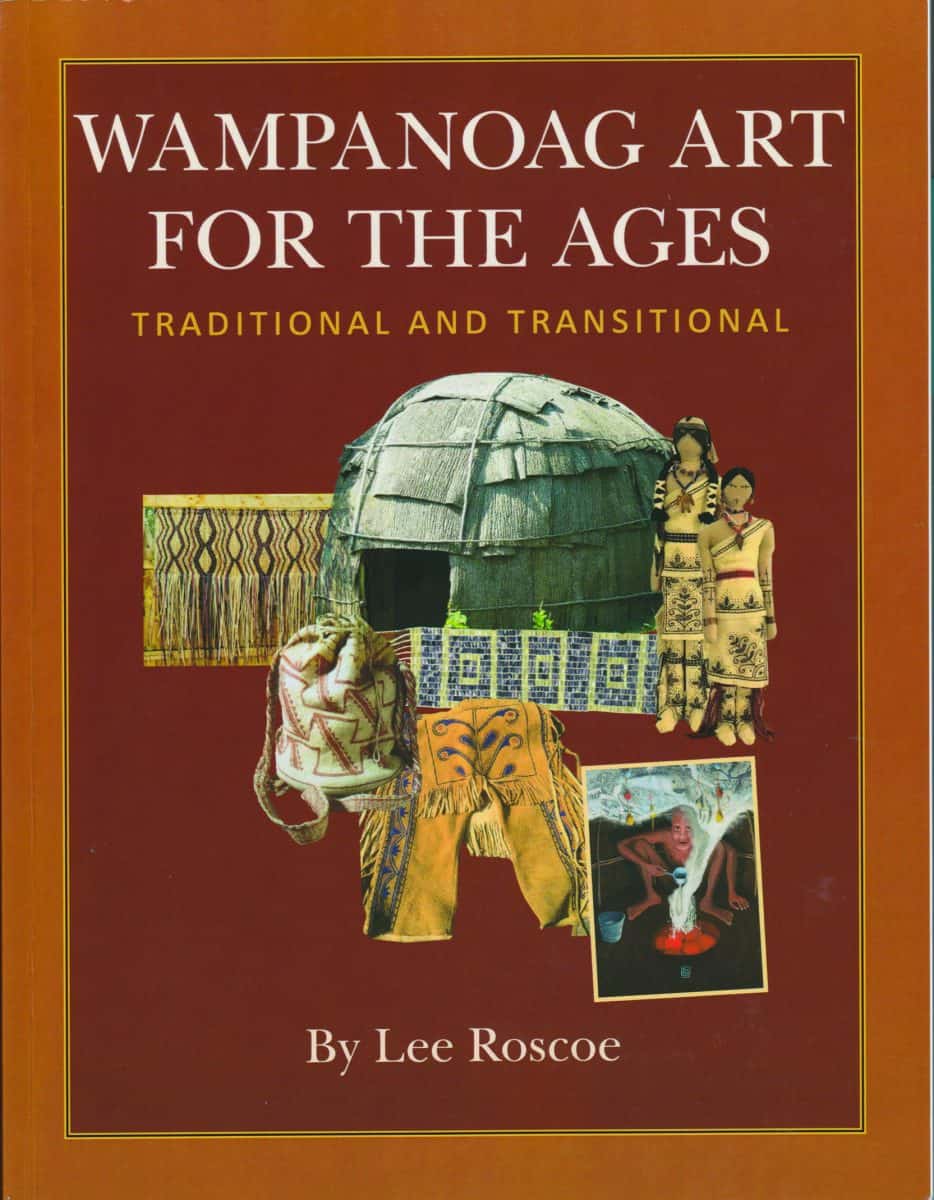

For writer Lee Roscoe, it was also a moment to bring attention to not just the past experiences of the Wampanoag people, but also to their continuing existence and specifically, the ways in which art and life were—and still are—intertwined for them. She wrote a piece for Provincetown Arts, but over a lifetime of interest in the subject, she had gathered enough information for a full manuscript. Earlier this year, that manuscript was published by Coyote Press as Wampanoag Art for the Ages: Traditional and Transitional.

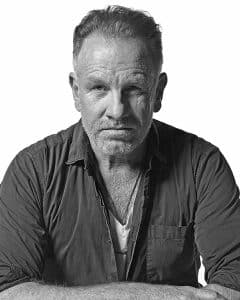

Photo: Webb Chappell, WGBH archives

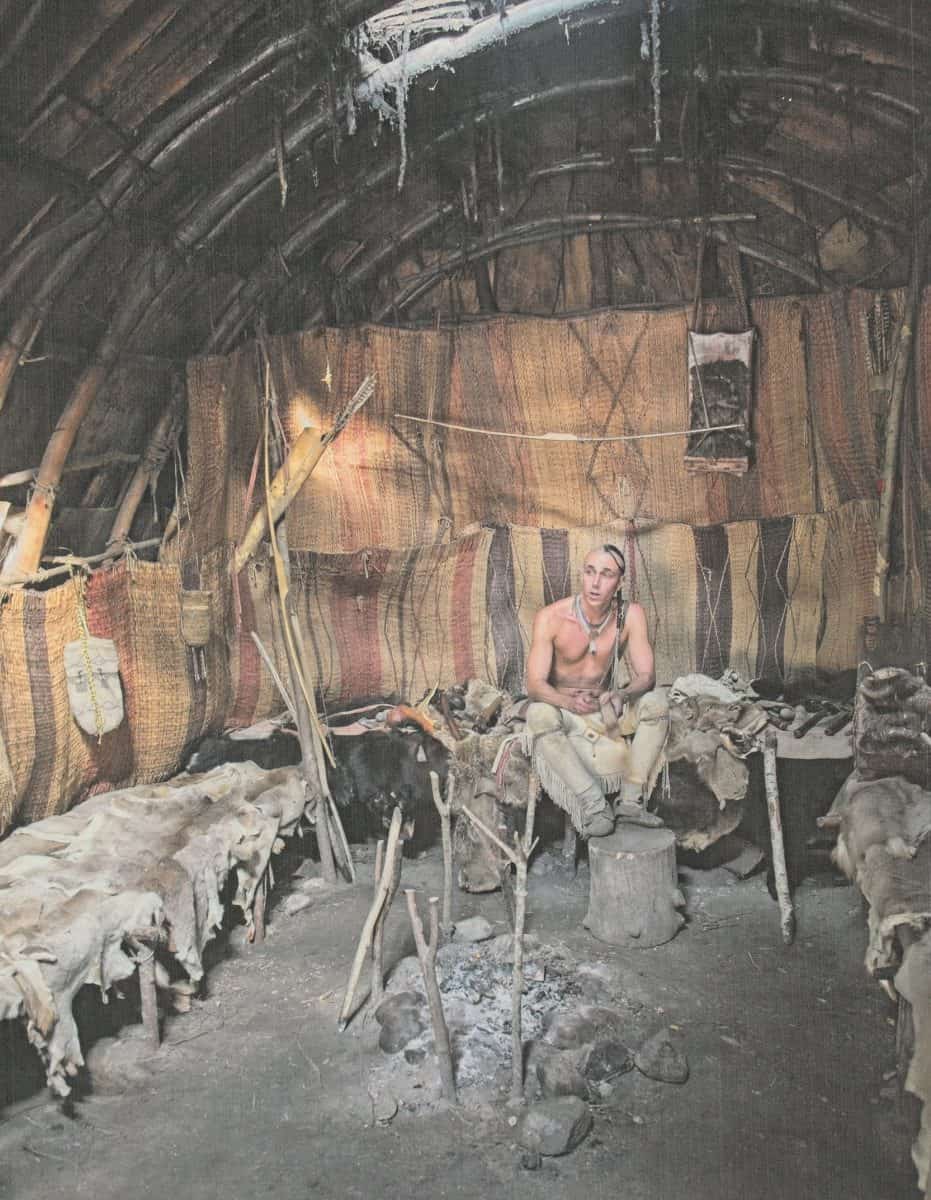

“I’ve been interested in the Wampanoag lifeway for decades. And when I was teaching environmental education, and well before that, actually, when I was still living in Manhattan, I tried to read everything possible about the history and as much as I could about the lifeway,” she explains. When she moved to Cape Cod she continued learning and had the benefit of being able to meet and get to know members of the Tribe here, becoming friends with Chief Earl Mills, for example. “When I got to know certain Wampanoag artisans and I got to know a little bit more about their material and spiritual practices, I just thought it would be a really cool thing to look at how they lived through their arts, starting in the wetu, which is the home, and looking at all the artifacts, which have art in them, such as pottery, regalia clothing, adornment, wampum, matting, twining, etc., and talk to artists about how they do their art, what their rationale is.”

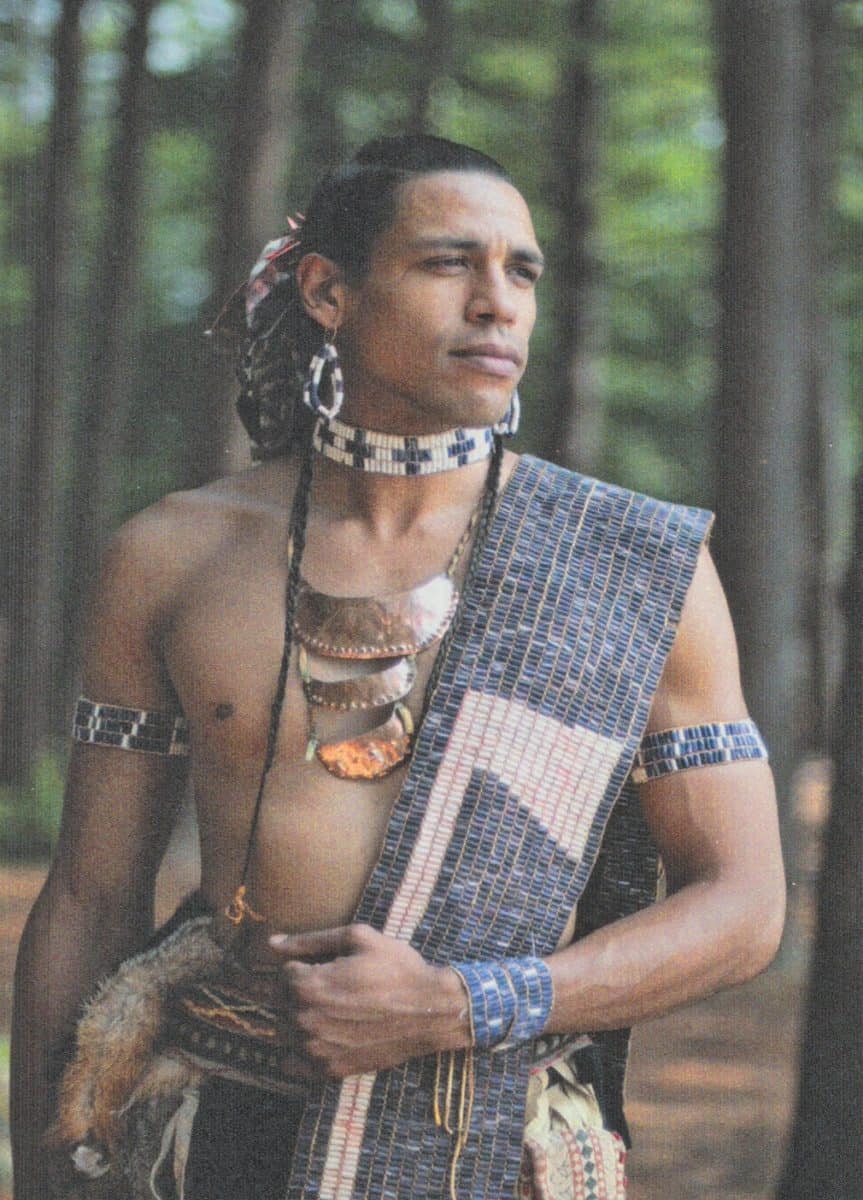

Photo: Richard Taylor

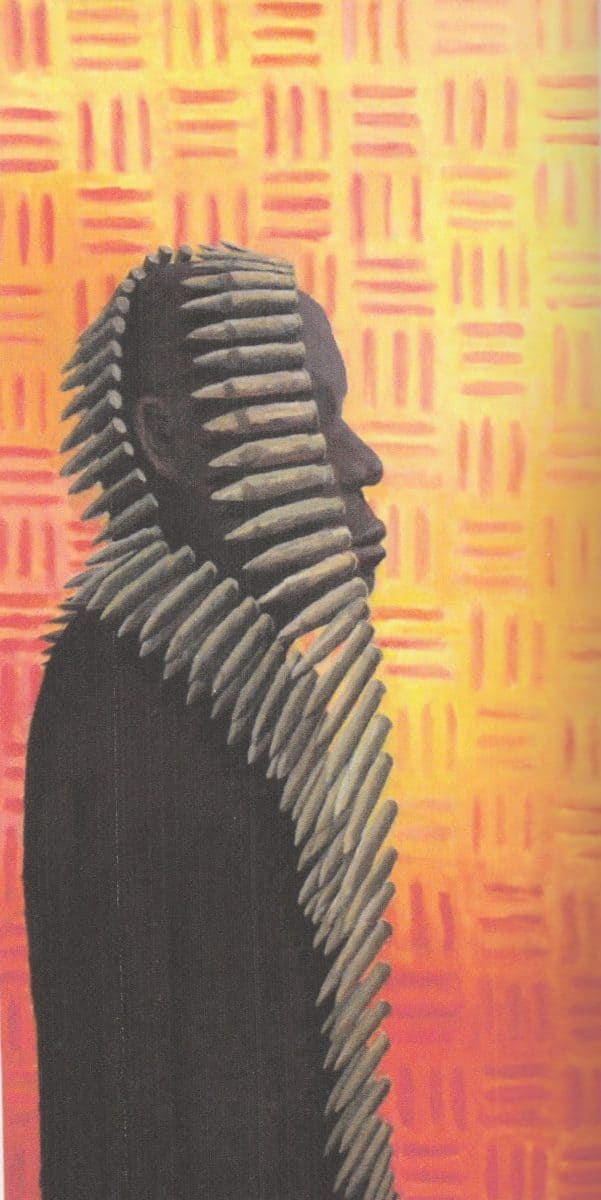

It’s not enough to correct the historical record; Wampanoag people still live here, and yet their creative output is typically relegated to historical museums rather than art museums. This is not the case around the country, where many artists included in the book have been able to show their work as art. Here in Provincetown, America’s oldest art colony, it seems particularly strange that art institutions don’t feature work by Native Americans from this area, who, after all, were making art here long before Henry Hensche and other celebrated early artists. It may have something to do with the distinctions between “art” and “craft” that have limited the art world for at least a century (a problem with roots in class systems, colonialism, and misogyny), but as Roscoe’s book makes clear, it is also a function of differing perspectives on what art is.

“All of the artists that I talked to are rooted in their ancestral traditions and they all thank their ancestors for bringing down the knowledge to them through those thousands of years that they’ve been here. But they also very much stress that they are of the present. They are still here. And they do their art—many of them, not all of them—with a modern twist,” says Roscoe. She gives an example of artist Anita Peters, also known as Mother Bear, who makes regalia based on traditional designs. “She always quips that she doesn’t need to go to the forest anymore to get sinew from deer. She can go to Joanne’s Fabrics,” Roscoe laughs. “That kind of embodies that perfect mix between past and present.”

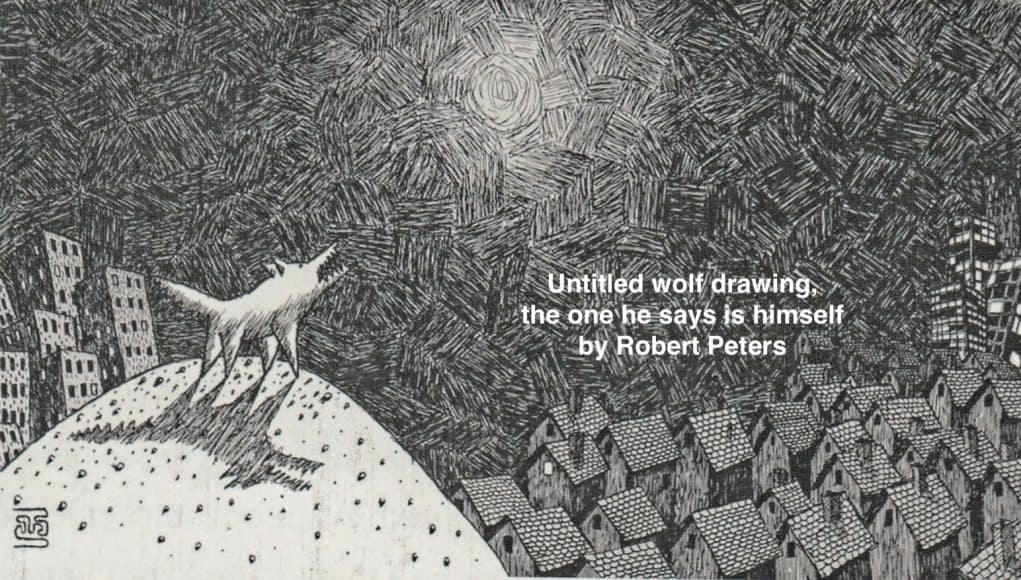

The book features artists who incorporated western perspectives into their work, such as painter Robert Peters and Emma Jo Mills Brennan, and also those who see the function of the work as its purpose rather than pursuing art for art’s sake. “I mean Annawon [Weeden], for instance, will say, ‘I don’t do art that hangs on a wall. No disrespect, but my art, even if it’s making a spoon or a mishoon—which is a dug-out boat—, it’s the art of living; it’s how we live. It serves the purpose it serves to use.’ But there are artists like Robert Peters, who is a painter and self taught, who draws on his traditions to create art that hangs on a wall. And that’s more like the transitional artists, like Emma Jo Mills Bremen, also very much rooted in her tribal traditions and rituals, but also does art that can hang on the wall,” she explains.

Roscoe has been involved with issues affecting Wampanoag people for many years, including gathering signatures in favor of federal recognition when the Tribe didn’t have it and helping to protect 300 acres of land in Marstons Mills, much of which is sacred to the Wampanoag. Still, she is careful to acknowledge she is not Native American, but rather an ally who brings her perspective to her work while being guided by her friends in the community. Asked about this delicate relationship, she cites her Jewish heritage as a bridge. “Coming from oppressed people, I identify with others who are oppressed,” she says. “Because I have suffered antisemitism, and I know what it’s like to be on the other side… I’ve always been able to talk to people who are outside of the dominant culture. And I did establish relationships with the Wampanoag through things that I’ve done over the years… So I think they got to know of me and trust me enough to give me the privilege of access.”

Wampanoag Art for the Ages by Lee Roscoe is available at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum, the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum, the Truro Historical Society and Highland Museum; the Wellfleet Historical Society, as well as many other bookstores on Cape Cod and beyond. For more information visit artistsandmusicians.org/wampanoag.

Wampanoag Artist Web Sites

Many of the artists featured in Lee Roscoe’s book have their own web sites where you can learn more about them and in some cases, purchase their work.

Hartman Deetz

Kerri Ann Helme

Marcus Hendricks

Julia Marden Bluejay’s Vision

Elizabeth James Perry

Jonathan James Perry

Robert Peters

https://xeepuuaee.wixsite.com/robert-peters-art/robert-peters-mashpee-wampanoag-art

Annawon Weeden

Jason Widdiss