by Steve Desroches

Even on the quietest of winter nights it’s never a surprise to see a warm glow coming out of the Provincetown Theater as the Bradford Street theatrical institution succeeds in being an incubator of creativity and imagination year-round. While presenting productions by established playwrights is an integral part of its mission, so is giving space and support for emerging playwrights on the Outer Cape. As part of that effort the Provincetown Theater established the Play Dates program, an opportunity for local playwrights to workshop new pieces of theater.

“This year’s spring Play Dates series has been going fantastically well,” says David Drake, the Theater’s artistic director. “Attendance to hear these new plays-in-development has been bountiful, and the way the audiences have been receiving them and discussing afterwards with the playwrights is a testament to the intelligence and hunger our community has for new works.”

The program, part of the Stephen Mindich Literary Project funded by Mindich’s widow, retired judge Maria Lopez, included this past winter presentations of work by Sarah Schulman and Racine Oxtoby, both of which packed the house, according to Drake. The series is wrapping up for the season now with two additional readings by playwrights Linda Fiorella and Jon Richardson, each offering vastly different new works, most notably one a comedic play and the other a musical.

Fiorella, who is also the town’s licensing agent, has explored a variety of writing genres, but came to writing dialogue for the stage by participating in the Provincetown Theater’s 24-Hour Play festival, in which a ten-minute piece is written, staged, and performed within one full day. Fiorella also participates in the theater’s playwright’s lab as well as Truro Playwright’s Collective at the Truro Public Library. When she first moved to the Outer Cape, Fiorella began to work on a novel that was a “lesbian love story set in the zombie apocalypse in Provincetown.” Fiorella laughs that she clearly has an “apocalyptic thing going on,” as her play, Beanie’s Last Stand, features a rag-tag group of queer people seeking shelter in a dune shack in an America now completely run by right-wing Christian nationalists. And it’s a comedy. The seed for this story began in the run-up to the 2020 election when Fiorella couldn’t bat away the thought of what would happen if Trump was reelected. She wanted to write about those feelings and fears, and while some people found themselves incredibly productive during the lockdown of the Covid pandemic, that was not the case for Fiorella.

“Every free moment was spent watching old Mary Tyler Moore reruns,” laughs Fiorella. “Comfort watching. That was it.”

However, she could not shake this idea she had, so once the pandemic eased and anxiety gave way to creativity, she was able to dive head first into bringing life to Beanie’s Last Stand. And after a successful reading this past winter at the Truro Public Library, Fiorella is excited to witness a Provincetown audience’s reaction to her play.

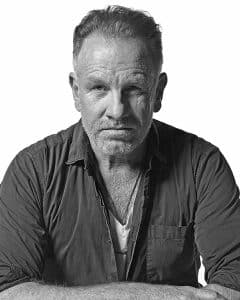

Much like Fiorella, Jon Richardson became haunted by inspiration, in his case to write a musical. His new work, titled Jack of Hearts, is a love story set in a gay cabaret in Provincetown in 1963 as the end of summer approaches. Richardson is well known as a piano man playing at the Crown and Anchor, as well as a musician in a variety of projects, including the folk duo Donnelly and Richardson, partnering with Todd Alsup for a Billy Joel and Elton John revue, and as a frequent guest star in the variety show the Provincetown Follies. But it was sitting at the keyboard night after night playing for tourists and townies alike that continually had him falling back in time to pre-Stonewall Provincetown.

“I first got the idea the first season I played piano bar, which was 2017,” says Richardson. “It’s just never really left my brain since.”

Richardson and Fiorella both shared a deep appreciation for how supportive the Outer Cape is in general to them and others when embarking on a new creative pursuit. And for Richardson, it was a dinner at Liz’s Café with David Drake back 2019 when he mentioned he had a few songs written and then for the first time he said aloud that he had an idea for a fully formed musical, to which Drake replied, “Yes! Yes! Yes!” Writing songs was a familiar journey, but how to write the book was the challenge. And so Richardson reached out to playwright and Truro resident Gary Garrison for advice. Garrison guided Richardson and will also direct Fiorella’s piece. Learning the different lyricism it takes to write a play was a thrill, says Richardson. And unlike for Fiorella, his reaction to the pandemic withdrew him into focusing on this project, sometimes working up to 7 or 8 hours a day on it. This reading at the theater marks the first time the entire work will be presented as prior to this he’d only presented snippets of dialogue and songs.

“These readings are so amazing, such an amazing opportunity,” says Richardson. “There aren’t many places that offer such opportunities and are so supportive to new works. I first thought I needed money. That I needed investors in my musical. I’d chat up anybody I saw wearing a Rolex in town and make my elevator pitch. But now I realize this is the kind of investment that gives life to art. This is where the road to Broadway begins. I’m so grateful and excited.”

The Spring Play Dates are at the Provincetown Theater, 238 Bradford St., with Linda Fiorella’s Beanie’s Last Stand on Thursday, April 13 at 7 p.m. and Jon Richardson’s Jack of Hearts on Thursday, April 20 at 7 p.m. Each reading is free, but a ticket is required and is available at the box office and online at provincetowntheater.org. For more information call 508.487.7487.